On December 4, 2025, Nate Persily, the James B. McClatchy Professor of Law at Stanford Law School and Senior Fellow at the Freeman Spogli Institute, spoke about election administration in the United States during a CDDRL research seminar. Persily discussed revelations from the 2024 election and how the 2024 election can forecast the upcoming 2026 midterm election cycle.

Persily started his talk by sharing the “Election Administrator’s Prayer”— "Oh God, whatever happens, please don't let it be close" — as close elections expose the “fragile underbelly” of the election administration system, like the 2024 election. Roughly 230,000 votes in key swing states ultimately determined Donald Trump’s Electoral College victory of 312 votes to Kamala Harris’ 226.

Persily situated the 2024 results within the broader political trends. Traditional political science predictors — public evaluations of the incumbent administration and economic perceptions — pointed toward a Trump victory. At the same time, public confidence in the electoral system shifted. Republicans’ confidence in the national vote increased markedly compared to 2020, while Democrats’ confidence declined — a reversal Persily described as a “sore-loser” pattern, but a decline that saw greater change with Democrats than in past years.

Persily narrowed in on the act of voting itself, and firstly covered vote-by-mail. He emphasized that vote-by-mail has a smaller partisan gap than might be assumed: states as ideologically diverse as Utah, California, and Washington rely heavily on all-mail voting. Nationwide, only about 34 percent of voters cast ballots on Election Day, reflecting a long-term move toward early in-person and mail voting. Persily emphasized that these categories themselves are increasingly fluid — voters may receive a mail ballot but choose to drop it off in person, complicating simple partisan narratives about “mail voters” versus “in-person voters.”

In 2024, states sent 67 million ballots to voters, and 72 percent were returned. About 1.2 million mail ballots were rejected, primarily due to missing or mismatched signatures — an issue concentrated among younger voters with inconsistent signatures and older voters experiencing age-related variation. Persily identified signature verification as a potential spot for further controversy, given its susceptibility to litigation, partisan pressure, and administrative inconsistency. In-person voting, by contrast, saw few changes from 2020. Approximately 1.7 million provisional ballots were cast, with 74 percent ultimately counted.

Notably, several anticipated threats to the 2024 election did not materialize. Despite widespread discussion about AI-generated disinformation, deepfakes largely appeared in satirical contexts with little evidence of voter confusion. Fears of widespread voter suppression, election-related violence, and breakdowns in certification procedures were also less present than expected.

Persily highlighted several emerging risks that might impact the 2026 election cycle. Firstly, efforts to target overseas ballots for active military and overseas citizens (UOCAVA), particularly in Michigan, North Carolina, and Pennsylvania, have increased, as have general efforts to review and purge voter rolls, signaling a growing interest in using administrative disputes to challenge ballot eligibility.

Another concern was the over 227 bomb threats made against polling places and election offices, which led a few polling places to temporarily close or extend hours. The concern here is not necessarily the explosives themselves, as no explosives were found. Rather, Persily warned that voters might not go to the polls for fear of violence.

Other challenges included wide variation in county-level rules for curing mail ballots, particularly in Pennsylvania, where some counties offer robust curing opportunities, and others offer none — raising equal-protection concerns reminiscent of Bush v. Gore. Persistent state-level differences in counting speed, with California as the slowest, create openings for misinformation about “late-counted” ballots. Election-official turnover continues to rise, leaving many jurisdictions with less experienced administrators heading into 2026.

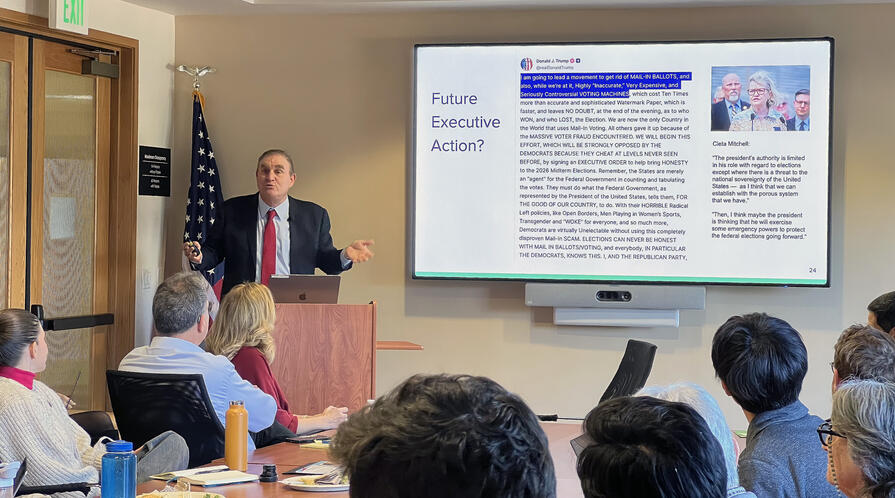

Persily then turned to new sources of pressure. A recent executive order requiring documentary proof of citizenship — paired with DHS review of state voter lists — could impose significant burdens, as many U.S. citizens lack passports or have name discrepancies with their documentation. On Truth Social, President Trump has also floated eliminating mail voting entirely and even ending the use of voting machines. Since May 2024, the Department of Justice has requested voter-registration databases from at least 21 states, heightening tensions over data privacy and federal authority. Persily raised concerns about the potential deployment of federal troops or ICE at polling places, noting that such actions are illegal but still feared.

Persily lastly outlined what he called a “nuclear option.” A constitutional loophole allows Congress’s ability to refuse to seat duly elected members on the basis of qualifications, which then proceeds to a vote to seat a new member. This loophole, if used, could result in back-and-forth objections where no one is able to claim their seat.

Persily emphasized the need for states to commit resources to speeding up mail-ballot counting, for courts to resolve executive-order challenges before the 2026 cycle begins, for early in-person voting to be encouraged, and for the House to articulate rules about objections to member seating well before November 2026. Ultimately, Persily argued that although most Americans will experience the 2026 elections as the same as elections in past years, states with competitive congressional districts may feel the strain.

Persily ended by saying the present tension in our voting systems does not favor centralization, and perhaps, federalism is our friend at this current moment.