A World Safe for Autocracy: How Chinese Domestic Politics Shapes Beijing's Global Ambitions

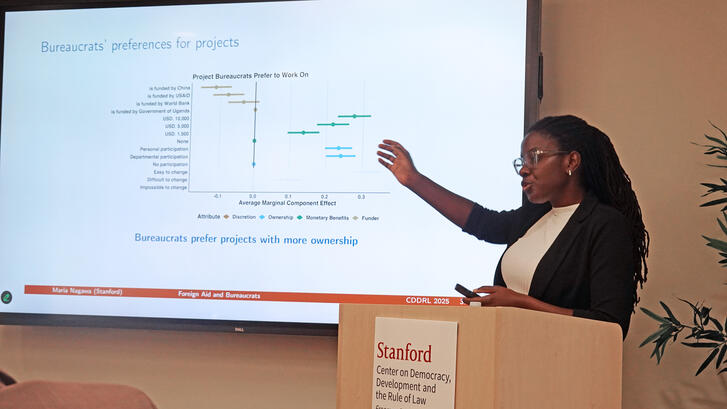

At a recent seminar hosted by APARCʼs China Program, Professor Jessica Chen Weiss, the David M. Lampton Professor of China Studies at the Johns Hopkins University's School of Advanced International Studies, presented findings from her forthcoming book, Faultlines: The Tensions Beneath China's Global Ambitions (under contract with Oxford University Press), which examines how domestic politics and regime insecurity shape China’s foreign policy ambitions, prospects for peaceful coexistence, and the future of international order. Drawing on research and fieldwork in China, Weiss argued that understanding Beijingʼs behavior on the world stage requires looking beyond ideology to the contested priorities and political calculations that drive decision-making within the Chinese Communist Party (CCP).

Weiss proposed a framework centered on three pillars that have sustained CCP legitimacy since the late 1970s: sovereignty (nationalism), security (civility), and development. Her analysis reveals that China's objectives are not static but moving targets shaped by competing domestic interests, leadership priorities, and international pressures.

Sign up for APARC newsletters to receive our event invitations and programming highlights >

The Sovereignty-Security-Development Paradigm

At the heart of Weissʼs argument is the recognition that the CCPʼs foremost concern is domestic survival. In the face of the collapse of most communist regimes, the Party has remained vigilant against what it calls “peaceful evolution” and democratic contagion.

On issues touching core sovereignty concerns – Taiwan, Hong Kong, and maritime territorial claims – China has been “hyperactive” in making demands, even when doing so invites international censure. Weiss explained that the more central an issue is to CCP domestic legitimacy, the harder it becomes to make concessions, and the more likely international pressure is to backfire.

Yet tensions exist between competing priorities. China has compromised on certain border disputes to shore up domestic security, while its evolving stance on climate change reflects a shift from viewing carbon limits as threats to growth to recognizing the greater threat environmental catastrophes present to the nation’s stability.

Beyond the Monolith: China's Internal Contestation

Weissʼs research demonstrates that authoritarian China is far from monolithic. Different geographic, economic, institutional, and even ideological interests shape policy debates, even if most actors lack formal veto power. Local governments can resist central directives, as evidenced during the COVID-19 outbreak, when local officials initially withheld information about human-to-human transmission from the central government to prevent panic from disrupting important political meetings.

This pattern of center-local tension extends to China's international commitments. Local officials often game environmental regulations to juice growth and secure promotions, undermining Beijingʼs pledges on carbon emissions. On issues ranging from Belt and Road investments to export controls, implementation frequently diverges from stated policy as local actors pursue their own interests.

Weiss’s framework distinguishes among issues that are both central and uncontested (such as Taiwan), those that are central but contested (like climate change and trade policy), and peripheral issues where Beijing has shown greater flexibility (such as demonstrated by many UN peacekeeping initiatives). This helps explain why international pressure succeeds in some domains but fails spectacularly in others.

"The more central an issue is domestically, the more pressure the government faces to perform, and the harder it is to defy these domestic expectations," Weiss said. As a result, international pressure on these central issues is more likely to backfire, forcing the government to be seen as defending its core interests. She underscored that "even on these central issues, there's often tension with other central priorities, and managing these trade-offs comes with a number of different risks. It also means that sometimes an issue that touches on one pillar of regime support can yield to another."

Nationalism as Constraint and Tool

Weiss described nationalism as both a pillar of the CCPʼs legitimacy and a potential vulnerability when the government’s response appears weak. While large-scale anti-foreign protests have become rare, nationalist sentiment remains active online and shapes diplomatic calculations.

During Speaker Nancy Pelosiʼs 2022 visit to Taiwan, Chinese social media erupted with calls for the PLA to shoot down her plane. One interlocutor told Weiss his 14-year-old son and friends had stayed up past bedtime to watch Pelosiʼs plane land, illustrating nationalismʼs penetration into Chinese society.

Survey research reveals Chinese public opinion is quite hawkish, with majorities supporting military spending and viewing the U.S. presence in Asia as a threat. The government often refrains from suppressing nationalist sentiment to avoid backlash, even when doing so creates diplomatic complications. Weissʼs public opinion survey experiments, however, reveal that tough but vague threats can provide the government with wiggle room for de-escalation, although disapproval emerges when action is not sufficiently tough.

Regime Security Without Ideological Crusade

Weiss pushed back against arguments that China is bent on global domination or that ideology drives conflict with the West. While the CCP seeks a less ideologically threatening environment, it must balance this against development and market access.

This pragmatic calculus explains China's constrained support for Russiaʼs war in Ukraine — Beijing fears secondary sanctions more than it values autocratic solidarity. Rather than exporting revolution, China has worked with incumbents of all political stripes in the service of its national interests.

Chinaʼs strategy focuses on making autocracy viable at home, not on defeating democracy globally. This suggests room for coexistence if both sides can reach a détente on interference in internal affairs.

“China's activities are making autocracy more viable and, to the extent that China is succeeding, making China's example more appealing as a consequence. But its strategy doesn't hinge on defeating democracy around the world,” argued Weiss. This implies, to her view, that “there is more room for coexistence between autocracies and democracies if these different systems can find or reach a potential détente in the realm of ideas about how countries govern themselves, and importantly, they need to pull back their efforts in other societies across boundaries.”

Interdependence and Future Trajectories

Weiss concluded by outlining how her framework suggests different engagement strategies depending on where issues fall within the centrality-contestation matrix. On central but uncontested issues like Taiwan, pressure proves counterproductive, and reciprocal restraint may be most promising. On central but contested issues like currency, multilateral pressure can influence certain Chinese constituencies against others. On peripheral issues, such pressure is most effective unless powerful domestic constituencies subvert implementation.

Addressing questions about U.S.-China decoupling, Weiss noted that both sides recognize there are interdependencies that don’t have quick solutions. Even in a critical area like minerals, diversification will take at least a decade, and Chinese processing will still dominate globally. The goal of diversification should be to preempt coercion, not to achieve true decoupling.

Read More

China studies expert Jessica Chen Weiss of the Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies reveals how the Chinese Communist Partyʼs pursuit of domestic survival, which balances three core pillars, drives Beijingʼs assertive yet pragmatic foreign policy in an evolving international order.

- Chinaʼs foreign policy is driven by three domestic pillars: The CCPʼs pursuit of sovereignty, security, and development creates competing priorities that shape Beijingʼs assertiveness on core issues like Taiwan, while allowing flexibility on peripheral concerns such as UN peacekeeping.

- International pressure often backfires on central issues: The more important an issue is to CCP domestic legitimacy, the harder it becomes to make concessions, meaning external pressure regarding Taiwan or territorial disputes tends to strengthen rather than moderate Beijingʼs position.

- China is not monolithic: Local governments, industries, and different Party factions contest policy implementation, creating gaps between Beijingʼs stated commitments and actual behavior on issues ranging from environmental regulations to trade.