People Shaping AI: Groundbreaking Industry-Wide Forum Invites Public Input for the Future of AI Agents Through Public Deliberation

In an unprecedented collaboration, Stanford's Deliberative Democracy Lab has spearheaded the first-ever Industry-Wide Forum, a cross-industry effort putting everyday people at the center of decisions about AI agents. This unique initiative involving industry leaders Cohere, Meta, Oracle, PayPal, DoorDash, and Microsoft marks a significant shift in how AI technologies could be developed.

AI agents, advanced artificial intelligence systems designed to reason, plan, and act on behalf of users, are poised to revolutionize how we interact with technology. This Industry-Wide Forum provided an opportunity for the public in the United States and India to deliberate and share their attitudes on how AI agents should be deployed and developed.

The Forum employed a method known as Deliberative Polling, an innovative approach that goes beyond traditional surveys and focus groups. In November 2025, 503 participants from the United States and India engaged in an in-depth process on the AI-assisted Stanford Online Deliberation Platform, developed by Stanford's Crowdsourced Democracy Team. This method involves providing balanced information to participants, facilitated expert Q&A sessions, and small-group discussions. The goal is to capture informed public opinion that can provide durable steers in this rapidly evolving space.

As part of the process, academics, civil society, and non-profit organizations, including the Collective Intelligence Project, Center for Democracy and Technology, and academics from Ashoka University and Institute of Technology-Jodhpur, vetted the briefing materials for balance and accuracy, and some served as expert panelists for live sessions with the nationally representative samples of the United States and India.

"This groundbreaking Forum represents a pivotal moment in AI development," said James Fishkin, Director of Stanford's Deliberative Democracy Lab. "By actively involving the public in shaping AI agent behavior, we're not just building better technology — we're building trust and ensuring these powerful tools align with societal values."

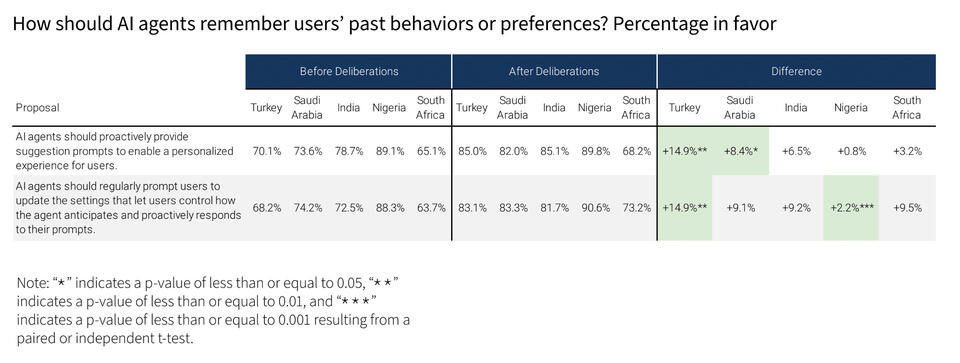

The deliberations yielded clear priorities for building trust through safeguards during this early phase of agentic development and adoption. Currently, participants favor AI agents for low-risk tasks, while expressing caution about high-stakes applications in medical or financial domains. In deliberation, participants indicated an openness to these higher-risk applications if provided safeguards around privacy or user control, such as requiring approval before finalizing an action.

The Forum also revealed support for culturally adaptive agents, with a preference for asking users about norms rather than making assumptions. Lastly, the discussions underscored the need for better public understanding of AI agents and their capabilities, pointing to the importance of transparency and education in fostering trust in these emerging technologies.

"The perspectives coming out of these initial deliberations underscore the importance of our key focus areas at Cohere: security, privacy, and safeguards,” said Joelle Pineau, Chief AI Officer at Cohere. “We look forward to continuing our work alongside other leaders to strengthen industry standards for this technology, particularly for enterprise agentic AI that works with sensitive data."

This pioneering forum sets a new standard for public participation in AI development. By seeking feedback directly from the public, combining expert knowledge, meaningful public dialogue, and cross-industry commitment, the Industry Wide Forum provides a key mechanism for ensuring that AI innovation is aligned with public values and expectations.

“Technology better serves people when it's grounded in their feedback and expectations,” said Rob Sherman, Meta’s Vice President, AI Policy & Deputy Chief Privacy Officer. “This Forum reinforces how companies and researchers can collaborate to make sure AI agents are built to be responsive to the diverse needs of people who use them – not just at one company, but across the industry.”

Through Stanford’s established methodology and their facilitation of industry partners, the Industry-Wide Forum provides the public with the opportunity to engage deeply with complex technological issues and for AI companies to benefit from considered public perspectives in developing products that are responsive to public opinion. We hope this is the first step towards more collaboration among industry, academia, and the public to shape the future of AI in ways that benefit everyone.

“We have more industry partners joining our next forum later this year”, says Alice Siu, Associate Director of Stanford's Deliberative Democracy Lab. “The 2026 Industry-Wide Forum expands our discussion scope and further deepens our understanding of public attitudes towards AI agents. These deliberations will help ensure AI development remains aligned with societal values and expectations.”

For a full briefing on the Industry-Wide Forum, please contact Alice Siu.

Read More

In an unprecedented collaboration, Stanford's Deliberative Democracy Lab has spearheaded the first-ever Industry-Wide Forum, a cross-industry effort putting everyday people at the center of decisions about AI agents.