SIPR Lema and Ngwenya

China’s Role in Regional Integration in Africa: The Case of East African Community

Introduction

Since the independence of African states, regional integration has been widely regarded as vital for facilitating economic development in Africa. However, evidence on the ground suggests this process has been constrained by internal weaknesses and fragmentations, stemming from Africa’s diverse political, economic, social, and cultural attributes. Yet, the emergence of new actors in the continent’s economic landscape -namely, its ‘special’ partnership with China - seems to be offering African leaders and development practitioners a new opportunity to consider how regional integration can be achieved.

Importantly, regional economic communities (RECs) have become the building blocks in advancing sustainable development in Africa under the aegis of the African Union (AU). One of the pillars enshrined in the mandate of the AU is to assist nations to realize their potential through sub-regional integrations. As such, it is important to consider the extent to which RECs are able to incorporate their regional integration agendas into common positions and build response mechanisms in their interactions with the surging number of external players, including China, the European Union (EU), the United States, and India, among others.

Striving to meet these challenges, the East African Community (EAC) has intensified its efforts to accelerate its political and economic integration in the region. Since its revival in 2000, the EAC has made considerable progress in its integration efforts.[1] The ultimate objective of such integration efforts is the establishment of a single market characterized by internal free trade, a monetary union, and eventually a political federation.[2] The bloc has consistently identified enhancing trade, as well as improving and expanding regional infrastructure, as priority areas to achieve optimal integration.

As Africa’s leading trade partner and a key contributor to its infrastructure development, China has been active in East Africa through trade, infrastructure financing, and construction. Despite this involvement and a growing canon of literature dealing with various aspects of China-Africa relations, not much attention has been paid to the role China plays in Africa’s region-building. To close this gap in the extant literature, this paper specifically looks at China’s approach to infrastructure (both hard and soft) development in the EAC and analyzes China’s trade policies towards the Community. We focus on these two sectors because infrastructure development and trade promotion have consistently been featured in the EAC’s development strategies to date, showing their centrality in advancing integration for sustainable regional development. They are also the areas in which Beijing is most active in the bloc, given it boasts the strongest infrastructure construction capabilities in the world. More importantly, China’s investment in infrastructure and stimulation with the EAC through enhanced trade is consistent with the trend of their increasing use of economic development for diplomacy and building broader regional influence. It follows a similar pattern in places such as Latin America, Southeast Asia through the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), and East Asia. Although these broader trends fall outside of the scope of this paper, it is important context for considering China’s motivations and how the EAC should approach the relationship.

This paper argues that though China’s active role in infrastructure development has the potential to help the EAC overcome some of its regional integration challenges, Beijing’s trade practices could be a stumbling block. China’s trade practices in the region, coupled with the bloc’s inability to adopt a unified trade policy toward the Asian giant could effectively derail the EAC’s integration momentum. Using the EAC as a case study, the analysis helps close the gap in the extant literature on China’s role in Africa’s region-building efforts. The research also furthers our understanding of China’s role in the EAC’s integration efforts, an understanding that could better inform policy decisions.

The remainder of the paper is divided into three main sections. The first section briefly provides a background on the EAC, its evolution as a regional body, and its economic and trade strategies. The second section looks at China’s infrastructure investments in and trade policies toward the EAC. It also examines the implications of China’s actions in these sectors on the EAC’s integration efforts. The last section wraps up the analyses and provides some recommendations on how the EAC could capitalize on China’s presence to accelerate its integration process. These analyses allow us to gain a deeper understanding of China’s role in EAC’s integration efforts and, by extension, they may also help us better understand China’s potential role in region-building in the African continent.

The East African Community: An Overview

After many failed attempts at establishing a regional bloc, the East African Community (EAC) was reborn on July 7, 2000, following the ratification of East African Community Treaty.[3] The founding partner states included Tanzania, Kenya, and Uganda.[4] Burundi and Rwanda joined the bloc in 2017 as the EAC was consolidating its governance mechanisms and structures as well as policy implementations. Five years after its independence, South Sudan joined the regional body in 2016, completing the EAC’s membership list.

With more than 195 million people, the population of the EAC exceeds the entire population of the nine countries of Western Europe that includes Germany, France, the Netherlands, Belgium, Austria, Switzerland, Luxemburg, Monaco, and Liechtenstein.[5] Moreover, the EAC is not just the fastest integrating regional bloc in Africa but also the fastest growing regional economy of the continent with a GDP growth at about 6 percent in 2019 from an estimated 5.7 percent in 2018.[6] Regarding integration, a 2014 report by the African Development Bank (AfDB) states that the EAC has made the most linear progress toward economic union and shown the highest ambition of any other REC in Africa.[7] Likewise, the AfDB’s 2019 African Economic Outlook concludes that “The East African Community (EAC) Common Market Protocol is one of the most ambitious globally.”[8] The ultimate aim of the EAC’s integration efforts is to create a common currency, which will eventually be followed by a political federation. These efforts to date have culminated in the establishment of a customs union in 2004, the launch of a common market for goods, labor, and capital in 2010, and the adoption of a protocol in 2013 to launch a monetary union by 2023.[9]

In its latest Doing Business report, the World Bank described how countries within the EAC made a total of 314 regulatory reforms towards improving the overall regional business climate.[10] Many of these reforms were targeted towards improving accessibility of electricity, getting credit, protecting small investments, and trading across borders. These reforms are evidence of the EACs desire to establish itself as Africa’s leading regional economic hub. Moreover, looking at the indicators on trade across borders, the report found that the EAC has the second lowest time for cost to export in relation to border compliance at the regional level, after the Middle East and North Africa (MENA). More specifically, in comparison to MENA ($442.40), Sub-Saharan African ($605.80), and the Southern African Development Community ($654), the EAC has one of the lowest average cost to export in relation to border compliance with $427.80.[11]

In their dealings with external players such as China, RECs in Africa are striving to harmonize national infrastructure investment and trade plans within a regional framework, which leads to economies of scale and translates into more affordable prices for businesses and consumers. This brings down production costs and makes Africa more competitive internationally. Regional power pools can create continental energy markets with coordinated supply systems and intra-trade could accelerate integration and development efforts across the continent. This is exactly what the EAC is trying to achieve in its efforts to involve Beijing.

China and the EAC’s Integration Efforts

China has a long history of interaction with the East African region, but that interaction largely took place through individual government relations. And though Beijing has publicly stated its support for Africa’s region-building efforts, it was only in November 2017 that the Asian giant accredited its envoy to the EAC in order to accelerate a cooperative relationship between the two parties.[12]

This section examines China’s role in the EAC’s integration efforts. More specifically, it first analyzes China’s contribution to infrastructure development in the region, including Chinese financing and construction in transport, information and communications technology (ICT), and energy sectors. By so doing, the study gauges the influence of these infrastructure projects on the EAC’s regional integration agenda. Moreover, the analysis covers Beijing’s trade policies toward the bloc and how they influence its integration efforts.

China in the EAC’s Infrastructure Development: A Promising Marriage

China has been playing a prominent role in infrastructure developments in the EAC, with its enablement of Chinese construction companies to put their expertise to test and gain access to new markets, while at the same time helping the region reduce its staggering infrastructure deficit.[13] China’s activeness in the region’s infrastructure development, however, gained even greater momentum with the launch of what has become the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI)—a flagship of China’s global ambition. The BRI has played a facilitating role in the cooperative efforts between EAC partner states over regional infrastructure developments and the Chinese financing and construction of mega-projects.[14] Furthermore, just like in other sectors, it has provided a significant boost to the EAC’s efforts to construct new railways and improve the efficiency of the already existing transport corridors in the region.

In that regard, to assert that the EAC is under construction is to state the obvious, as the regional bloc has come to realize the important role infrastructure plays in allowing countries to achieve their national development objectives and regional integration. In their report on infrastructure development in Africa, Edinger and Labuschagne (2018) pinpoint that the EAC is a rising regional star, with partner states in the bloc intensifying their efforts to upgrade and expand their infrastructure. Interestingly, the majority of the identified projects (84.2 percent) are government-owned, indicating the important role played by East African governments as facilitators of infrastructure development through national and regional development policy plans.[15] These efforts are well in line with the regional policy plans anchored in the EAC’s Vision 2050 that calls for the bloc to promote inclusive and sustainable development through improved regional integration.[16]

For its part, China has become a leading player across Africa in infrastructure development, including in the EAC, both as a prominent financier and a leading contractor. Beijing signed a Framework Agreement with the EAC in November 2011 to focus on promoting, among other things, co-operation in investment and infrastructure development in the region.[17] During the signing ceremony, the then EAC Secretary General Richard Sezibera observed that the “EAC requires approximately US 80 billion dollars in infrastructural investments for the period up to 2018. This investment for sure will not be raised within this region and we are, therefore, extending a hand of friendship to Chinese investors to work with us and take advantage of the huge potential for investment.”[18] The emphasis on investment in infrastructure projects should not be surprising because it is a sector in which both the EAC and China have great interest.

Not only has productive infrastructure proven crucial in developing countries’ attempts at industrialization and, more essentially, diversification, it is also the motor for inclusive economic development, poverty alleviation, and regional integration. Investment in infrastructure—especially connective infrastructure projects—plays a significant role in boosting business confidence and fostering innovation and productivity.[19] Similarly, investment in infrastructure also helps lower transaction costs, making it easier for companies to move labor and products, as well as provide quality services.[20]

According to Edinger and Labuschagne (2018), foreign direct investment (FDI) also tends to increase with the development of infrastructure, which provides a breeding ground for facilities the transfer of skills, technical know-how, and best practices between foreign and domestic companies. However, while only 12.9 percent of projects in the region in 2018 were funded by East African governments, China’s infrastructure finances in the region stood at 25.9 percent, illustrating the significant role China has been playing in infrastructure development in the regional bloc.[21] But China's mounting position as a key infrastructure financier and a leading contractor is not limited to just the EAC region: the story is similar all across the African continent. In 2018 alone, for instance, it financed nearly one in five infrastructure projects across the continent while also undertaking the construction of over half of all the projects.[22] But if China has effectively established itself as a leader in Africa’s infrastructure development efforts, its focus has been dominated by the transport sector. Remarkably, 38.6 percent of the Chinese-financed infrastructure projects in Africa aim at improving transportation networks.

A similar development has been unfolding in the EAC. In their report, Edinger and Labuschagne (2018) show that investment in connective infrastructure continues to dominate the overall infrastructure development efforts in the wider East African region.[23] The transport sector accounts for 45.3 percent of all projects in the region and takes 26.6 percent of the finances, in terms of U.S. dollar value. By comparison, the closest second is energy and power projects, accounting for a significantly lower share at only 18.0 percent and 21.1 percent in value terms.[24]

Despite the gap, however, there is a compelling rationale for transport, energy and power sectors to dominate in infrastructure development projects in the region. Plainly put:

“The focus on these sectors reflects the fact that a well-developed transport network as well as reliable energy supply and access are integral to the East African Community’s (EAC) Development Strategy. Completion of Kenya’s US$3.2bn Nairobi- Mombasa rail line – built and funded by Chinese construction companies and financiers respectively – marks the completion of the first phase of the intraregional railway line that will eventually extend to Uganda, Rwanda, South Sudan… Regional projects such as these demonstrate a shift towards trade enabling infrastructure that aims to spur intra-Africa trade and integration. Furthermore, alignment through regional projects allows African economies – particularly smaller economies – to participate in collective bargaining, making it easier for them to secure funding for infrastructure projects.”[25]

Thus, it is safe to make the case that China’s investments in infrastructure play a significant role in helping the EAC’s partner states reduce their infrastructure deficit individually and collectively. The investments also boost the EAC’s regional connectivity as well as integration efforts. For this reason, China’s mounting role in the EAC’s regional infrastructure development (see below the summary table of some of these major infrastructure projects) should be seen as positive, potentially enhancing cross-border mobility of labor, capital, and products in the region and foster intra-regional trade. Therefore, where infrastructure development in the EAC is concerned, Beijing contributes positively to the integration process through connective finances and enabling trade across the region and far beyond.

Table 1: Summary Table of Some of the Major Chinese Infrastructure Projects in the EAC

|

Geographical Location |

Project Description |

Estimated Costs (USD) & Status |

|

TRANSPORT |

||

|

Kenya |

Nairobi-Mombasa 472km long Standard Gauge Railway |

3.2 billion, Complete |

|

Nairobi-Naivasha |

1.5 billion, Ongoing |

|

|

Tanzania |

Bagamoyo Port Construction and Special Economic Zone |

10 billion, Delayed |

|

South Sudan |

Juba International Airport Renovations |

160 million, Complete |

|

ENERGY |

||

|

Uganda |

Karuma Hydropower Dam |

1.7 billion, Complete |

|

Kenya |

Lake Turkana Wind Power Station |

858 million, Complete |

|

Loiyangalani–Suswa 400 Kilovolt Transmission Line Project |

271 million, Complete |

|

|

Burundi |

Chinese-aid-to-Burundi International Hydroelectric Dam |

70 million, Ongoing |

|

INFORMATION AND COMMUNICATIONS TECHNOLOGY (ICT) |

||

|

Tanzania |

10,674-kilometre national fiber optic backbone |

170 million, Ongoing |

|

Uganda |

E-Government Network System |

106 million, Ongoing |

|

Rwanda |

Electronic World Trade Platform (eWTP) |

Unknown Cost, Ongoing |

Transportation Sector

Thanks in large part to the Chinese investments and expertise, the EAC partner states have been able to undertake the construction of some major mega-infrastructure projects in the transport sector. As Mathieson (2016)’s report correctly pinpoints, transport infrastructure has become a leading priority for the regional bloc. These efforts are geared towards more cooperation over reducing non-tariff barriers, the construction of railways, and improving port efficiency in the EAC. The ultimate objective of closing the infrastructure deficit in the region is to boost trade and connectivity in the region and far beyond.

Under the latest EAC Development Strategy, for instance, the modes of transportation identified as focal development areas include the expansion of road and railway networks, sea and lake ports, and air transportation. The EAC adopted what is known as the Railway Master Plan designed to rejuvenate the railway industry across the region, instituting standardization with the Standard Gauge Railway (SGR), and expanding the railway network in order to help achieve timely and efficient transportation of long-distance freight.[26] Given that only two EAC partner states (Tanzania and Kenya) have direct access to the sea, strengthening railway networks is more than just strategic; it is also an effort to enhance trade connectivity with landlocked partner states. The Railway Master Plan identifies the Northern and the Central corridors as central to maximizing regional connectivity for the EAC.

In this regional effort to bolster railway connectivity, China has emerged as the primary investor for the Northern corridor. Furthermore, it is important to note that China is no stranger to supporting railway projects in this specific region, having pioneered the Tanzania-Zambia railway in 1976. In May 2017, the Chinese-financed 472-kilometer-long SGR connecting Mombasa, where Kenya’s largest port is located, to Nairobi opened ahead of schedule.[27] Chinese investment, made through its Exim Bank, financed more than 80 percent of the total cost of the railway development. To demonstrate the impact this railway has, Pheiffer (2017) described how the Mombasa-Nairobi railway line decreased traveling time by exactly a half from initially nine hours to four and half hours. Furthermore, it is projected that shipping via freight would increase from only four percent to 40 percent by the year 2025.[28] President Kenyatta also secured additional funding from China to extend the railway line westward to Naivasha. The construction of the project is undertaken by China Road and Bridge Corporation (CRBC) and financed by Exim Bank of China.[29] The expansion plans are a backdrop to a larger and more ambitious plan in the wider East Africa aimed at extending the railway line to connect land-locked South Sudan, eastern Democratic Republic of Congo, Rwanda, Burundi, and eventually Ethiopia, which will then directly connect with Djibouti giving it direct access to the Indian Ocean.[30] Indeed, this ambitious regional expansion is not only a means of advancing the goal of the EAC integration but; it also serves as a realization of a key objective of China’s BRI, as seen in other global regions in Central East Asia with the Angren-Pap Railway line in Uzbekistan and East Asia with Gwadar Port in Pakistan, just to name a few.

However, Kenya is currently facing hurdles in the sense that countries like Uganda and Rwanda are now dithering on their commitment towards the railway expansion directly through their territories. One could argue that there has been an overreliance on Chinese financing, which has also raised a sense of doubt over the regions’ capability to finance this mega infrastructure project. Moreover, the extent to which China has been readily willing to invest in the railway sector within the EAC should be analyzed more in-depth. For example, it was reported that in 2018 China denied Uganda’s $2.3 billion loan request that was meant to fund its own phase of the SGR regional efforts. In 2019, Uganda resubmitted the loan request with additional information and additional links to other ports not mentioned in the first request.[31] But The East African reported in early March 2020 that this latest request was also rejected, though negotiations are believed to be ongoing.[32] Therefore, one should be critical of the actual role China is playing in assisting the EAC achieve its goals set in the Railway Master Plan.

Another area to consider is port development. Once again, China has been actively involved in developing ports in both Kenya and Tanzania, both of which are seen as the central players for regional connectivity in the EAC. For instance, with the construction of the Lamu Special Economic Zone through the China Merchants Port Group Company Limited (CMPort), Kenya aims to position itself as a regional hub of global standard ports.[33] Tanzania, on the other hand, has faced immense setbacks with the proposed Bagamoyo Port and Special Economic Zone, estimated at $10 billion, stalled for the past seven years over issues on reaching mutually beneficial terms also known as “win-win cooperation.”[34] This demonstrates that collaborative efforts towards achieving the EAC’s regional integration by strengthening transportation and infrastructural development have not always been without challenges.

Information and Communications Technology (ICT)

In order to further the mandate of creating EAC into the regional innovative hub of Africa, the bloc has been guided by the EAC Protocol for Information and Communications Technology (ICT) for all ICT infrastructure and policy-related developments. Thus far, the EAC has managed to establish the EAC Framework that has seen a cross-border broadband internet-connections network setup.[35] Furthermore, the regional body has adopted the EAC Road Map for broadcast migration.[36] The EAC partner states have leveraged China’s pivotal role in this new digital era, especially with Beijing being a pioneer of the 5G revolution.

China’s role in the regional development of communications infrastructure illustrates how this form of infrastructure development can be used as a means to further regional integration. In Tanzania, the government signed a reported$ 170 million contract in 2009 with a Chinese vendor to lay the country’s 10,674 kilometer national fiber optic backbone. The second phase has been financed by a $100 million concessional loan of the Exim Bank of China.[37] It has been reported that the completion of the first phase closed a significant gap in the East African fiber ring, connecting to the SEACOM, TEAMS and EASSy submarine cables and running from Kenya through Uganda, Rwanda and Burundi to Dar-es-Salaam, Tanzania.[38] A similar investment was also made in Uganda, whereby China implemented telecommunications projects, connecting all Ugandan ministries to an e-government network, establishing a government data center, and connecting 28 Ugandan districts to the national ICT backbone.[39] Developing the ICT infrastructure among the EAC countries helps set up network systems that can be accessed and used across the borders to facilitate more efficient communication and exchanges, which would in turn attract more investors and promote innovation and competitiveness.

Energy Sector

The EAC has recognized the need to bolster its energy sector and has set up policy mechanisms to address this need. From a regional perspective, the EAC has been reported as having the lowest per capita power generation and electricity generation across the African continent.[40] Other than low energy generation, the region also struggles with low coverage and higher tariff costs. Through the EAC Power Master Plan, it has articulated the need to establish a Regional Power Market that will guarantee the advancement of a regional energy framework, including the EAC Cross-Border Electrification Policy. Working with stakeholders such as the Eastern Africa Power Pool (EAPP) and the United Nations Community for Africa, the EAC is making collaborative efforts in improving the energy generation in the region.[41] China has also emerged as a collaborator in furthering the EAC’s energy generation goals.

According to a study, a total of 28 Chinese-backed power generation projects would have been either planned, under construction, or completed in East Africa between 2010 and 2020.[42] This represents over a quarter (29 percent) of the total Chinese-backed power projects in sub-Saharan Africa. Furthermore, a total of 21 Chinese-backed transmission and distribution line projects are either planned, under construction, or completed in East Africa. This represents 43 percent of all Chinese-backed transmission and distribution line projects in Sub-Saharan Africa.[43] Among the highest countries receiving Chinese added capacity power projects between 2014 and 2024, EAC has representation with Uganda being the 4th largest receiver after Zambia, Nigeria, and Angola.[44] This demonstrates China’s active role in East Africa’s energy sector. Furthermore, the OECD (2016) report elaborated on how these Chinese projects correspond to greater economic growth in East Africa and Southern Africa. There is also a wider mix of technologies from Chinese projects, including in non-hydropower renewables, in the Eastern and Southern regions. China’s infrastructure investments in the EAC, therefore, can be seen as directly helping address the staggering infrastructure gaps that are preventing the region from unlocking its latent growth potential. In Uganda, Chinese investment through the Sinohydro Corporation and a loan from Exim Bank of China has allowed the construction of the Karuma hydropower dam, which was set to increase Uganda’s total electricity generation capacity to 55.5 percent by the end of 2019.[45] Kenya has also made strides in its energy development through PowerChina’s construction in Lake Turkana Wind Power Station and the Loiyangalani–Suswa 400 kilovolt Transmission Line Project.[46]

From these analyses, it is evident how China’s prominent role in infrastructure development has “…enabled EAC member states to start to realize their shared interest in pursuing an ambitious infrastructure development agenda to address the infrastructure deficit throughout the region.”[47] However, it is worth noting that China’s involvement in these projects largely takes place through bilateral agreements with partner states as opposed to engaging the EAC directly. Moving forward, China could make more effort to directly communicate with the EAC, especially since it is already playing an indirect role in the region’s integration efforts with infrastructure financing and construction.

China-EAC Trade Relations: Things Falling Apart

It is obvious that China’s investment in infrastructure projects in the EAC plays a crucial role in enabling cross-border mobility of labor, capital, and goods. It also helps improve inland-hinterland connectivity in the region as well as the region’s logistical efficiency, all of which point to China’s positive contribution to the EAC’s regional integration efforts. However, promoting and improving regional infrastructure development is just an element, a factor of, integration. As such, this section analyzes China’s trade policies toward the regional bloc. The aim is to fathom Beijing’s role, through its trade practices and relations, in the EAC’s integration efforts. Since regional integration, as the EAC envisions it, is an integrated wholeness—including infrastructure development, trade promotion, etc.—this analysis will help us better understand the overall role China plays vis-à-vis the EAC and its integration endeavors. The importance of infrastructure development cannot be overemphasized. But the need to couple that development with the right trade policies, so as to encourage positive spillovers and unlock the regional economic potential, cannot be overstated either. Hence, what role does China’s trade policies toward the EAC play in the latter’s integration process?

A good place to start would be to recall that Beijing does not have a clearly established and unified regional trade policy toward the EAC. Unlike China’s trade involvement with the ASEAN through the ASEAN-China Free Trade Area (ACFTA) framework, its trade policies with the EAC bloc is built on bilateral relations, notwithstanding the Framework Agreement signed in 2011 that seeks to open up additional opportunities for Sino-EAC investment and trade relations. This should not be surprising because while China may openly work within the African continent through multilateral forums such as the Forum on China-Africa Cooperation (FOCAC), trade deals and investment agreements are predominantly formed on a bilateral basis.

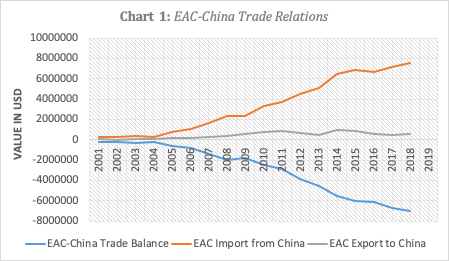

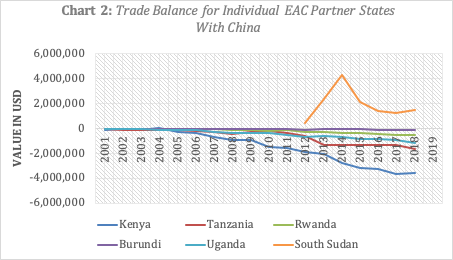

Bilaterally, China’s trade with the EAC’s partner states has been on the rise since the founding of the regional bloc, partly due to the expanding market in the region, a result of its population growth and rising purchasing power. Indeed, similar to its infrastructure finances, China has become one of the largest trading partners for the EAC’s partner states, both individually as well as collectively. Despite the booming economic ties between Beijing and the EAC bloc, China’s role in facilitating the regional integration through trade is questionable at best and detrimental at worst.[48] China’s exports to the region, just like to the whole continent, is characterized by cheap consumer and producer goods. And while these products may provide more options for consumers at affordable prices, local producers may end up losing due to competitive pressure from China.[49] The result will be recurring failed attempts at industrialization and development of home-grown industries that stifle export capacity. Indeed, as Chart 1 and 2 illustrate, the EAC’s exports to China have remained somewhat stable while its imports from the country have been constantly rising. The result has been a surging trade deficit (see Chart 1).

Even Jiang Yaoping, former Chinese Vice Minister for Commerce, recognized that China’s imports from the EAC are still low, and mostly characterized by natural resources, with little to no value-added. During the signing ceremony of the Framework Agreement between the EAC and China in 2011, Jiang Yaoping acknowledged that the partnership is disproportionately skewed in favor of Beijing: "We want to turn the EAC's resource strength to industrial strength to increase the currently low trade volumes from EAC to China…"[50] But it is not just the volume of the EAC’s exports to China that is an issue, it is also the nature—the type of products that are exported that is the foundation of the imbalance.

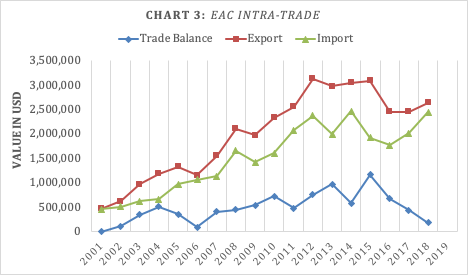

Yet, nearly a decade later, not much has changed. Thus, where regional integration through trade with Beijing is concerned, a major threat to the EAC’s efforts is the limited capacity of its partner states to trade among themselves due to the aforementioned competitive pressures from Chinese products (see Chart 3, which shows how intra-trade in the EAC is still low). This has a significant risk of diverting trade efforts and, in the process, repeating the failed colonial and traditional dependency development endeavors. Indeed, as Chart 2 shows, all EAC partner states, except for South Sudan (mainly thanks to its oil reserves that China buys), are increasingly running a considerable trade deficit due to the imbalanced trade relations with Beijing. Moreover, a breakdown of the EAC’s export products reveals that partner states share a number of similarities in what they produce and export to Beijing.[51] Unfortunately, since there is no policy coordination for their exports, these states have to compete among themselves for market share in China. As a result, the EAC’s current trade relations with China may undermine not just the former’s intraregional trade, especially in the manufacturing sector—due to China’s well-established competitive advantage and the economies of scale in the sector—but also its capacity to improve and diversify exports to China.

It is for this reason that Onjala (2013) argues that:

“The expanding trade between China and the regional market [EAC] provides a direct threat to the future viability of the economic integration since the process is likely to undermine many of the trading benefits envisaged in the formation of EAC integration. Besides, the competitive pressures put [the regional bloc’s] industrialization [efforts] in jeopardy.”[52]

Yet one of the primary reasons the EAC has been pushing for further integration is to strengthen economic and trade relations among its partner states so as to promote accelerated, harmonious, and balanced development within the EAC.[53]

Nevertheless, to better deal with these challenges, there have been discussions on establishing a free trade agreement between China and the EAC bloc. Although it is an encouraging development that Beijing wants to trade with the EAC partner states as a bloc, it is unclear how that move could help the bloc close the deficit. With the growing trade imbalance (see Chart 1 and 2), it is no wonder that those talks have not yet come to fruition. Especially Kenya, the country running the largest trade deficit with Beijing in the region (see Chart 2), has been particularly vocal in its opposition to the idea.[54] For instance, Kenya imported goods worth $3.61 billion from China in 2018 while exporting $104.85 million in goods to China. Given this unsustainable trade balance, Nairobi has been advocating for a preferential, non-reciprocal arrangement with Beijing to prevent a further surge in imports from China that would dampen the region’s industrialization prospects. In response to Kenya’s concerns, however, Chinese Ambassador to Kenya Wu Peng said in June 2019 that Beijing was ready to open trade talks with Kenya and the other EAC partner states. It was also reported that talks would be guided by World Trade Organization rules. These are certainly encouraging developments, and the EAC should capitalize on China’s flexibility to push for terms of trade that ensure its development and further integration, rather than its demise.

In short, China’s current trade policies toward the EAC seems to greatly threaten the region’s integration prospects by jeopardizing intraregional trade and growing their trade imbalance vis-à-vis Beijing. But emerging talks on a trade deal between the two parties should allow the East African countries to push for more favorable trade relations including boosting their industrialization efforts as well as guaranteeing transfers of technology and technical know-how to the regional bloc.

Conclusion

The paper analyzes the role China plays in the EAC’s integration process. Specifically, it examines Beijing’s contribution to the infrastructure development in the bloc through Chinese financing and construction. It also analyzes China’s trade policies toward the East African bloc and their influence on the region’s integration endeavors. From these analyses, it is shown that while China is indirectly promoting or facilitating the EAC’s integration by financing and building infrastructure projects (i.e., ports, hydro-electric power plants, telecommunications, roads and railway), its current trade policies vis-à-vis the bloc significantly threaten to derail the integration efforts.

To successfully mitigate such a blowback, the EAC and its partner states will need to adopt unified policies in dealing with Beijing, both for infrastructure development projects and trade relations. In this regard, the EAC could learn from China’s relationship with ASEAN. But to succeed, the EAC should be given a more prominent role to play in coordinating relations with the Asian giant. Not only will that help streamline interactions between the two parties and foster transparency, it will also ensure cooperation and coordination within the East African bloc. Moreover, the East African regional body could also work better with Chinese financial institutions dealing with regional infrastructure development in the region to ensure more transparency and accountability in order to avoid financial burdens arising from unsustainable projects and corrupt deals.

On their part, partner states will need to think more strategically when engaging China and overcome their existing differences and rivalries, including border tensions andrade disputes, among others that have hindered their ability to effectively form relationships with external actors like China. This requires working closely together in promoting integration in the EAC and in dealing with Beijing. It also requires formulating coherent regional policies on how best to stimulate China as a bloc, rather than individually as is the case today. If handled properly, both the regional bloc and China stand to greatly benefit from the stimulation in the region. While Beijing’s participation in developing infrastructure networks has the potential to boost the EAC’s integration efforts, it should not be lost that developing infrastructure across the region is only one aspect of the integration efforts. The efforts require having the right economic and social development policies in place. Where engaging Beijing through trade is concerned, the EAC will need to push for better trade relations with China. Such efforts would foster regional integration by both increasing trade capacity and diversifying export destinations. They could also allow the EAC’s partner states to harmonize their trade policies toward China, focus more on their respective comparative advantage, and possibly set common prices for their identical exports products to the country.

Finally, in promoting its regional infrastructure networks, the EAC should be mindful of other equally daunting challenges such as the security and environmental implications of these projects and whether they will bring about sustainable and inclusive development for the region and all its people.

[1] Hamid R. Davoodi, "The East African Community: After Ten Years Deepening Integration," International Monetary Funds, 2012.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Aloysius Uche Ordu, “Headwinds toward East African regional integration: Will this time Be different?” Brookings, April 22, 2019. https://www.brookings.edu/blog/africa-in-focus/2019/04/22/headwinds-towards-east-african-regional-integration-will-this-time-be-different/. The idea of creating such a bloc in the region can be traced as far back as 1917 when Kenya and Uganda formed an East African customs union characterized by free trade and a common external tariff scheme. Tanganyika (now part of Tanzania) joined the initiative in 1927. After independence, the three countries agreed to relaunch a regional body for integration in 1967, but the experiment only lasted one decade and spectacularly collapsed in 1977. See Ordu (2019) for further details on these developments and chronic failures.

[4] Ibid. The idea of creating such a bloc in the region could be traced as far back as 1917 when Kenya and Uganda formed an East African customs union characterized by free trade and a common external tariff scheme. Tanganyika (now part of Tanzania) would also join the initiative in 1927. After independence, the three countries agree to relaunch a regional body for integration in 1967. But the experiment would only last one decade as it spectacularly collapsed in 1977. See Ordu (2019) for further details on these developments and chronic failures; Ordu, 2019.

[5] Ibid.

[6] AfDB, “African Economic Outlook 2019: Macroeconomic performance and prospects.”;

Aloysius Uche Ordu, 2019.;

PML Daily, "East African Community set to benefit from DRC’s inclusion into regional bloc," June 17, 2019, https://www.pmldaily.com/news/2019/06/east-african-community-set-to-benefit-from-drcs-inclusion-into-regional-bloc.html#:~:text=KAMPALA%20%E2%80%93%20The%20East%20African%20Community,increasing%20from%205.9%25%20in%202018.

[7] UNCTAD, "East African Community Regional Integration: Trade and Gender Implications," (UNCTAD, 2017), 13.

[8] AfDB, African Economic Outlook 2019, 82.

[9] Craig Mathieson, The political economy of regional integration in Africa - The East African Community (EAC). (Maastricht: ECDPM, 2016), 5.

[10] World Bank Group, "Doing Business East African Community," (World Bank Group, 2019), 60.

[11] Ibid.

[12] EAC, "China Accredits Envoy to EAC bloc, East African Community Headquarters," n.p. 2017, https://www.eac.int/press-releases/151-international-relations/899-china-accredits-envoy-to-eac-bloc.

[13] Craig Mathieson, "The political economy of regional integration in Africa," 2016.

[14] For further details on the BRI, see Belt and Road Initiative: https://www.beltroad-initiative.com/belt-and-road/.

[15] Hannah Edinger and Jean-Pierre Labuschagne, “If you want to prosper, consider building roads China’s role in African infrastructure and capital projects,” Deloitte, 2018, 21.

[16] See East African Community vision 2050: regional vision for socio-economic transformation and development. The document is available at: http://repository.eac.int/bitstream/handle/11671/567/EAC%20Vision%202050%20FINAL%20DRAFT%20OCT-%202015.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.

[17] See EAC Website, November 2011; available at: https://www.eac.int/trade.

[18] EAC, “Press Release: EAC and China Sign Framework Agreement to Boost Trade, Investment”, East African Community Secretariat.

[19] Richard Bluhm, et al., "Connective financing: Chinese infrastructure projects and the diffusion of economic activity in developing countries," 2018.

[20] Edinger and Labuschagne, 2018, 2-30.

[21] Ibid., 21.

[22] Ibid.

[23] This includes Burundi, Comoros, Djibouti, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Kenya, Rwanda, Seychelles, Somalia, Tanzania, and Uganda. Though a partner state to the EAC since 2016, South Sudan was not included in this analysis.

[24] Edinger and Labuschagne, 2018, 7.

[25] Ibid, 20.

[26] EAC, "Development Strategy 2016/17-2020/21," 11-12.

[27] Evan Pheiffer, “Top 10: Africa Infrastructure Projects in 2018,” The Business Year, 2017.

[28] Ibid.

[29] Xinhua, “Kenya’s extended railway to boost trade hub status”, 2019;

Pheiffer, “Top 10: Africa Infrastructure Projects in 2018,” 2017.

[30] BBC, "Kenya opens Nairobi-Madaraka Express Railway," 2017.

[31] John Fidelis, “Uganda seeks US $2.3bn from China to fund SGR project,” Construction Review Online, 2019;

Tom Collins, “Kenya vs Tanzania: A tale of two railways,” African Business, 2019.

[32] The East African, “SGR: Exim Bank rejects Uganda loan request again”, 2020, https://www.theeastafrican.co.ke/business/SGR-Exim-Bank-rejects-Uganda-loan-request-again/2560-5482074-weyf6nz/index.html.

[33] Edwin Mutai, “Chinese company close to Sh250 billion Lamu Port special economic zone deal,” Business Daily, 2019.

[34] Reuters, “Tanzania's China-backed $10 billion port plan stalls over terms: official,” 2019, https://www.scmp.com/news/china/diplomacy/article/3013905/china-ready-t….

[35] EAC Development Strategy, 2016, 41.

[36] Ibid., 41.

[37] Tracy Hon, et al., "Evaluating China's FOCAC commitments to Africa and mapping the way ahead," (The Centre for Chinese Studies, 2010).

[38] Ibid.

[39] Ibid.

[40] EAC Development Strategy, 2016, 17.

[41] Ibid.

[42] OECD, “Boosting the Power Sector in Sub-Saharan Africa: China’s Involvement” 2016, 12.

[43] Ibid., 12.

[44] David Benazeraf, “Another look at China’s involvement in the power sector in Sub-Sahara Africa”, 2019.

[45] CNBC, “Uganda says its power generation capacity will jump 55 percent by end of year”, 2019.

[46] Power China, “Kenyan president cuts ribbons for two projects built by POWERCHINA,” 2019.

[47] Craig Mathieson, "The political economy of regional integration in Africa," 49.

[48] For a specific analysis on the impact of China’s trade with Kenya on Kenya’s development potential, see Joseph Onjala, “Merchandize Trading between Kenya and China: Implications for East African Community (EAC)”. In Adem Seifuden (ed) “China’s Diplomacy in East and Central Africa”. Routledge, 2013, 80-104;

Joseph Onjala, The Impact of China-Africa Trade Relations: The Case of Kenya (Working Paper No. CPB_05), African Economic Research Consortium (AERC), 2010;

Joseph Onjala, A Scoping Study on China-Africa Economic Relations: The Case of Kenya (Working Paper No. SSC_05), African Economic Research Consortium (AERC), 2008.

[49] Joseph Onjala, "Merchandize Trading between Kenya and China: Implications for East African Community (EAC)," 2013.

[50] EAC, 2011, 2, https://assets.aspeninstitute.org/content/uploads/files/content/images/ghd/China_EAC_Press_Release_11.17.2011.pdf.

[51] Joseph Onjala, "Merchandize Trading between Kenya and China: Implications for East African Community (EAC)," 2013.

[52] Ibid, 84.

[53] EAC, 2011.

[54] Reuters, 2019.