Do Incentives Matter When Politics Drive Emigration?

On January 15, 2026, Emil Kamalov, CDDRL’s 2025-26 Stanford U.S.-Russia Forum (SURF) Postdoctoral Fellow, presented his team’s research on whether autocracies can draw citizens who have emigrated back to their country of origin. Historically, episodes of autocratization create huge migration waves. In recent times, countries such as Chile, Venezuela, Iran, Belarus, and Russia have experienced waves of emigration as a result of authoritarian leadership. When skilled professionals who are crucial to their country’s functioning leave, a phenomenon known as “brain drain,” a central question arises: if and how these individuals will return. This raises two key questions: can autocracies reverse such a brain drain and bring their citizens back, or can only democracies do so?

Kamalov turns to the case of Russian migration to explore these questions more directly. For many Russians, the 2022 war with Ukraine was an initial trigger for leaving the country. Kamalov explains that autocrats use emigration as a safety valve to manage dissent at home. In doing so, autocrats rely on several tools to maintain control. These include selective “valving,” which allows some citizens to emigrate while retaining enough workers critical to industry, as well as imprisonment to punish those who attempt to leave. For those who have already emigrated, autocrats may introduce special policies, such as financial or tax benefits for critical professions, in an attempt to attract them back to the country.

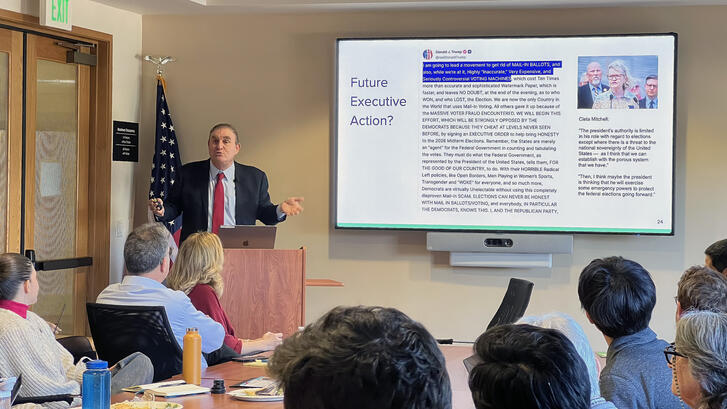

Kamalov then discussed what motivates citizens to move into and out of countries. He outlines a list of push and pull factors, including economic conditions, integration and discrimination, and satisfaction with amenities and services. He identifies a gap in the literature, noting that there is relatively little focus on politics — specifically regime change, autocracy, and democracy. From this gap, Kamalov poses several questions: can autocrats lure emigrants back with incentives, will people return if democratization occurs, and does democratic backsliding in host countries push emigrants back home? For political emigrants in particular, political liberties are non-tradable in their decisions about return.

Turning fully to the case of Russian emigration, Kamalov notes that about one million Russians have left the country since the February 24, 2022, invasion of Ukraine. This represents the largest brain drain since the collapse of the USSR. Forty-one percent work in the IT sector, and the majority of emigrants are highly skilled and educated, with many working in science, media, and the arts. This emigration represents a significant share of opposition-minded Russian citizens: most of those who left had experience with protest and civic engagement in Russia, and roughly 80 percent cite political reasons for their departure. In response, the Kremlin introduced several policies aimed at discouraging professional emigration or attracting emigrants back. These include mobilization exemptions for highly skilled workers in critical industries such as math, architecture, and engineering, as well as economic support for IT workers, including subsidized mortgages. Because of these policies, Russia serves as a useful case study for understanding whether the strategies autocracies use to entice citizens back or prevent them from leaving are actually effective.

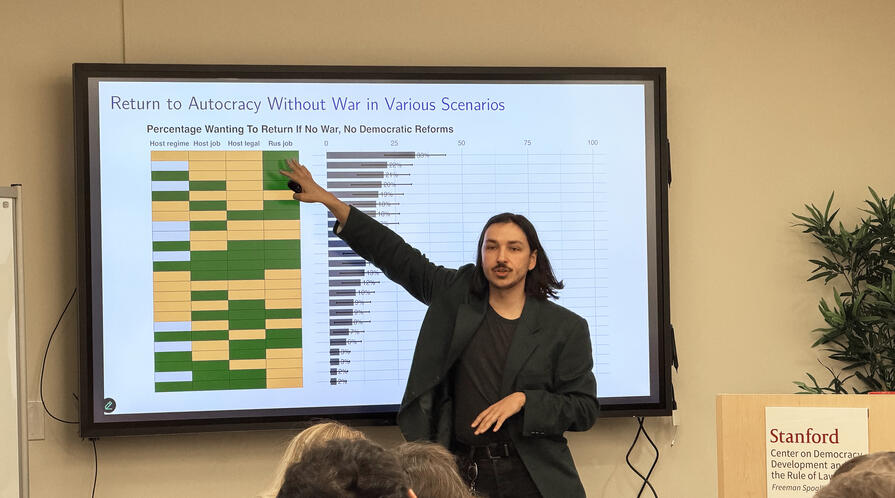

In March 2022, Kamalov and his team launched a panel survey of Russian migrants consisting of five waves. Approximately 21,000 post-2022 Russian emigrants across around 100 countries participated. As part of the survey, respondents were asked to imagine hypothetical political scenarios in Russia and indicate whether they would return if those scenarios became reality. These scenarios ranged from highly realistic but undesirable to unrealistic but highly desirable. They included continued war with Putin in power, continued war with family mobilization exemptions, an end to the war without regime change, an end to the war with political amnesty but no regime change, and full regime change with pro-democratic forces coming to power. The team also analyzed respondents’ host countries, focusing on economic conditions, citizenship opportunities, and political environments.

The results show that having a good job or a path to citizenship in the host country reduces the likelihood of returning to Russia, while democratic backsliding in the host country increases it. Draft exemptions do not increase return at all. Ending the war alone would attract only about 5 percent of emigrants, ending the war combined with political amnesty would attract about 15 percent, while democratization is by far the most attractive scenario, drawing around 40 percent back. When looking at subgroups, all professional categories studied — culture, IT, media, science, and education — were similarly unlikely to return under non-democratic conditions. During democratization, around half would return, though those working in culture, such as artists and musicians, were somewhat less likely to do so. Younger emigrants were more likely to return than older ones.

When asked why they would not return, respondents cited high migration costs, regime volatility, and distrust of Russian society. Some believed that even with political change, Russian society would take much longer to become progressive. Those who said they would return pointed to home, family, opportunities, quality of life, migration fatigue, and, in some cases, disillusionment with democracy in host countries.

The findings of Kamalov’s team demonstrate that even removing the initial trigger for emigration cannot attract many emigrants back. Job opportunities can draw certain subgroups, even during wartime, but broader political conditions matter far more. Autocratic spillovers and cooperation also matter, as democratic backsliding in host countries can motivate return. Importantly, even those who currently cannot envision retu

Read More

SURF postdoctoral fellow Emil Kamalov explains why political freedoms outweigh material benefits for many Russian emigrants considering return.

Maternal Migration Patterns and Child Development from Infancy to Early Adolescence: A Longitudinal Study in Rural China

The massive flow of migrants from rural to urban areas in China over the past decades has sparked concerns about the development of left-behind children. Drawing on a six-round, longitudinal cohort survey in rural China from 2013 to 2023 that follows children from 6 months to 11 years of age, we analyse the effects of two maternal migration patterns – persistent migration (migration without return) and return migration (migration followed by return) – on the cognitive development and nutrition of left-behind children from infancy to early adolescence. The results show that persistent maternal migration has adverse effects on the cognitive development and increased the BMI of left-behind children. In contrast, maternal migration had no significant effect on either cognitive development or any indicator of nutrition when the mother later returned. Persistent maternal migration had a strong, long-term negative effect on the cognitive development of left-behind children especially when mothers migrate within one or one and a half years after childbirth; maternal migration also had a short-term, negative effect on cognitive development when mothers migrate when the child is between 2 and 3 years old. These effects are likely driven by the lower levels of stimulating parenting practices and dietary diversity provided by the stand-in primary caregivers of left-behind children.

Emigration Policy Under Authoritarianism and Incentives to Break the Law

Introduction and Contribution:

Authoritarian regimes are often reluctant to let their citizens leave: 79% of autocracies restrict emigration compared to only 4% of democracies. This reluctance is understandable, as migration deprives rulers of talent, resources, and implied consent to the system. Yet autocracies do change their emigration laws. What are the consequences of these changes?

In “A Little Lift in the Iron Curtain,” Hans Lueders examines how a 1983 emigration reform in socialist East Germany (German Democratic Republic, GDR) affected crime rates in the country. The reform permitted about 62,500 citizens to exit the GDR over a short period of time — mostly to reunite with their families in West Germany. Lueders asks how this emigration affected crime. This is a natural outcome to consider because the former GDR, like many autocracies, used the emigration system to filter out individuals seen as criminals or “undesirables.” Unauthorized exit was criminalized, and some citizens committed crimes precisely to signal that they should be allowed to leave.

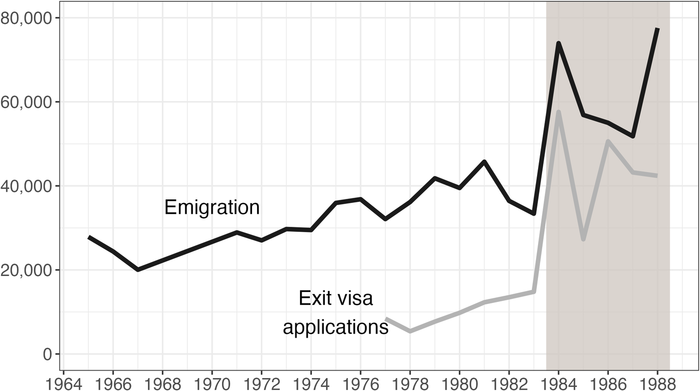

Figure 1: Consequences of the 1983 Emigration Reform

Note. This figure reports the number of first-time exit visa applications per year (gray line [Eisenfeld 1995, 202]) and annual emigration from the former GDR (black line; data collected by the author). The period after the emigration reform is emphasized.

Lueders shows that the effects of emigration following the 1983 reform on criminal activity depended on the type of crime. Ordinary kinds of crime — those not committed for political motifs — declined after the reform. However, border-related crimes increased sharply. This is ostensibly because those “left behind” (i.e., unable to take advantage of the 1983 reforms) resumed lawbreaking in order to pressure the regime to let them out as well. An analysis of petitions submitted to the state supports the idea that emigration raised demand for emigration.

The paper makes important contributions to our knowledge of authoritarianism and migration. For one, it shows how policies enacted to temporarily satisfy domestic or international audiences can backfire, later increasing the state’s burden. Autocrats may behave strategically in the short run, yet their choices can have powerful, unanticipated consequences in the years ahead. Otherwise, “strong” and repressive autocracies like the former GDR may struggle to address migratory pressures and be too inflexible to switch course after negative consequences become apparent.

Safety Valves and Reform in East Germany:

Social scientists have argued that emigration policy under authoritarianism can serve as a “safety valve,” allowing or forcing the exit of those who threaten the stability of the regime. In addition, requiring citizens to apply for exit visas acts as a “screening mechanism” because applying is politically costly; those who keep applying reveal themselves to be potential troublemakers whose exit ought to be permitted. Lueders provides evidence that the costs of applying for exit visas were indeed high in the former GDR: applicants (and sometimes their families) were intimidated and harassed by secret police, expelled from universities, and demoted or fired. The state also tried to “win over” prospective emigrants, showing them reports about the allegedly dismal living conditions in West Germany or letters from East German refugees begging authorities to return to the GDR.

Importantly, officials considered how emigration would influence the GDR’s stability, looking for those who opposed the country and its socialist vision. Many applicants realized this and thus sought to publicly challenge the regime, for example, by leaving socialist mass organizations or abstaining from voting. Committing crimes thus raised one’s chances of successfully emigrating. East Germans watched peers and family members break the law to force their exit, learning that the system encouraged and rewarded criminality.

After Germany’s division into two, many East Germans preferred the economic and political freedoms found in democratic West Germany. The government thus grew concerned: most émigrés were young and educated, and their exit undermined the GDR’s claims that it was popular and that socialism was the superior politico-economic system. Accordingly, emigration was criminalized in 1952, and the GDR began erecting physical barriers, culminating in the construction of the Berlin Wall in 1961. Emigration plummeted to between 25,000 and 40,000 per year thereafter.

Emigration remained severely limited until the early 1980s, when international pressure — from both West Germany and the Soviet Union — to reform its emigration system began to build. Ultimately, in September 1983, the GDR conceded and recognized the right of all citizens with family abroad to apply for an exit visa.

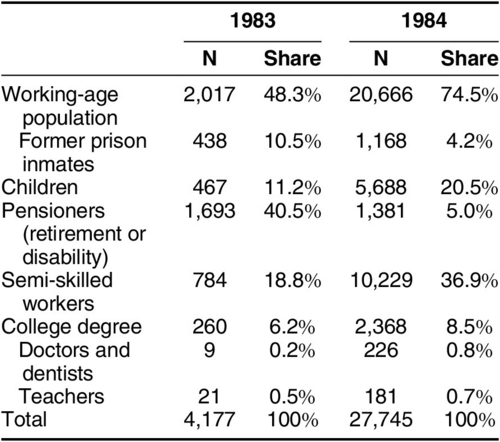

After the reform, exit visa applications and departures surged, the largest wave since the Berlin Wall’s construction. Emigration patterns evidenced a clear demographic shift: émigrés were less likely to be retired or to have formerly served in prison, while working-age East Germans made up 75% of emigrants, up from 49%. The state viewed this emigration wave as a welcome opportunity to get rid of criminals and political enemies. However, it underestimated the long-term consequences of offering some citizens a way out.

Table 1: Comparison of Emigrants in 1983 and 1984 (January to June of each year)

Data and Findings:

To measure the effects of the 1983 policy on crime, Lueders presents crime data from 1976 to 89. He divides crime into “ordinary,” e.g., against state property or persons, and “political” crimes, e.g., the use of force against state officials, treason, and, importantly, illegal border crossings. Two of Lueders’ key hypotheses for our purposes are that emigration reform led to (1) a decline in ordinary crime, because the GDR effectively removed so-called troublemakers (the safety valve mechanism), and (2) a rise in border crimes, because those left behind were willing to break the law in order to exit (the demand mechanism).

The statistical analysis — consisting of comparing places with varying emigration rates — is consistent with both hypotheses. For the most part, ordinary crime declined after 1983. By contrast, border crime also initially declined, but this pattern dramatically reversed within two years. By 1987, border crimes began to rise significantly in places that had experienced a lot of emigration in the initial wave. Lueders thus provides evidence that in the short run, emigration indeed functioned as a safety valve (i.e., criminals were successfully identified). But thereafter, emigration had severe repercussions: rather than alleviating pressure on the regime, it created even greater demand for emigration — and thus more criminal activity.

A final piece of evidence comes from detailed data on petitions. The GDR encouraged citizens to communicate a range of demands and grievances to state officials, including the desire to emigrate. Lueders shows that in 1984, over 16,000 petitions were written specifically about emigration, which constituted nearly 28% of the total number of exit visa applications. And these petitions for exit visas increased substantially more in areas with above-average emigration during the initial emigration wave, suggesting that greater emigration in one period was associated with greater demand for it in subsequent periods. An understanding of East Germany illustrates how autocrats face a delicate balance between permitting migration and managing its consequences.

*Research-in-Brief prepared by Adam Fefer.

CDDRL Research-in-Brief [4.5-minute read]

The Local Costs of Moving: How Residential Moves Weaken Local Engagement

How do residential moves influence movers’ engagement? Drawing on German household panel data, I demonstrate that moving leads to a temporary decline in local engagement but leaves national engagement unchanged. I theorize that this drop stems from weaker attachments to place, reduced local political knowledge, and disrupted social ties. Consistent with this interpretation, longer-distance moves — which tend to exacerbate these barriers — are especially disruptive to movers’ local engagement. I then use comprehensive administrative data on all moves in Germany to rule out an alternative mechanism: most moves occur between socio-politically similar environments, limiting opportunities for moves to influence engagement through contextual change. These findings depart from the prevailing focus in related scholarship on the United States, national engagement, and partisanship. By documenting the political consequences of domestic migration for local engagement, this study contributes to research on residential mobility and local democratic accountability.

Meet Our Researchers: Dr. Claire Adida

The "Meet Our Researchers" series showcases the incredible scholars at Stanford’s Center on Democracy, Development and the Rule of Law (CDDRL). Through engaging interviews conducted by our undergraduate research assistants, we explore the journeys, passions, and insights of CDDRL’s faculty and researchers.

Claire Adida is a Senior Fellow at the Freeman Spogli Institute’s Center on Democracy, Development and the Rule of Law (CDDRL), a Professor (by courtesy) of Political Science, and Faculty Co-Director of the Immigration Policy Lab at Stanford. Her research uses quantitative and field methods to investigate what weakens and strengthens social cohesion.

What is the most exciting or impactful finding from your research, and why do you think it matters for democracy, development, or the rule of law?

One of the most exciting findings from my work, and also from others in the field, is the role of empathy and perspective-taking in reducing prejudice and increasing inclusion. In one experiment during the height of the Syrian refugee crisis in 2016, we asked people to put themselves in the shoes of a refugee. We asked questions like, “What would you take with you? Where would you go?” When people engaged in that exercise, they became more open to refugees and more supportive of inclusion. And that was true across the political spectrum; Democrats and Republicans alike all showed greater openness after engaging in perspective-taking.

There is something really powerful about empathy. Other studies have shown the same pattern: when people imagine the perspective of someone different from them, whether it’s a refugee, a trans person, or an undocumented migrant, they become more understanding. It’s a simple but profound mechanism for building social cohesion.

How can empathy and perspective-taking be implemented on a larger scale, and how can they be used to address the challenges we see in the world today?

Well, this isn’t something you can legislate. You can’t tell politicians to force people to imagine someone else’s life. The real audience for this work is advocacy organizations like the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) or the International Rescue Committee (IRC), because they’re already doing it. They use storytelling and humanizing narratives in their campaigns all the time.

It’s really hard, though, because we’re living in what people call the attention economy, which is driven by social media. Everything is about visibility, clicks, and headlines, and there’s always a new crisis. It becomes difficult for people to hold on to empathy for more than a moment because the focus is constantly shifting from one story to another. Even if a big influencer were to advocate for refugees or displaced communities, another could just as easily come along and dehumanize them or spread misinformation that undermines this. So it becomes this constant tug-of-war between empathy and fear, between humanizing and othering.

With that being said, I think social media can also be used as a really powerful tool for sharing stories and reaching people who might not otherwise engage with these issues. It gives us a space to humanize experiences and make them visible at a scale that wasn’t possible before. The challenge is figuring out how to use these platforms not just to get attention for a moment, but to actually build connection and understanding that last beyond a single news cycle.

How does this translate into policy?

Ultimately, I do think that public opinion matters for policy. The way people feel about migration or refugees — whether they see them as part of the community or as outsiders — shapes which policies are politically possible. And today, public opinion is shaped more than ever by social media. It’s not just voters who are influenced by online narratives; policymakers and donors are too. That’s why empathy and communication are central to policymaking, as social media now plays such a major role in shaping how both the public and those in power think and respond.

Can you tell me more about your work at the Immigration Policy Lab?

I just joined as Faculty Co-Director and am currently leading two key projects focused on migration and development, particularly in the Global South.

One major area is climate migration, understanding how environmental shocks affect migration decisions. The people most vulnerable to climate change are often the poorest. We’re trying to understand how they perceive risk, what strategies they use to survive, and when migration becomes an option. We’re currently raising funds to collect data in places like Colombia and rural Guatemala.

Another big project focuses on return migration, looking at people who have been expelled or deported, as well as those who self-deport. We’re building partnerships with organizations like Mercy Corps and the IRC to study how they reintegrate, what challenges they face, and whether existing programs are actually helping.

What have been some of the most challenging aspects of conducting research in this field, and how did you overcome them?

I would say interest and funding. Studying migrant integration is not popular these days; it feels like everyone is obsessed with AI or how technology can solve problems. That also creates challenges with funding and resources, especially from federal sources, because projects like ours require long-term fieldwork and collaboration, which are expensive and time-intensive.

That said, I’ve been really fortunate to find a strong community and support system here at Stanford and at CDDRL. Being part of this environment has enabled me to connect with others who care about these issues and to find the resources needed to keep the work going.

What gaps still need to be addressed in this research, and what do you hope to study in the future?

I think a big gap that hasn’t been studied enough is who actually engages with empathy-based initiatives in the first place. We know that when people are asked to imagine themselves in someone else’s shoes, they become more open and inclusive. But who is voluntarily clicking on those websites or reading those stories? Probably people who already care. That’s a limitation, because it means we might just be reinforcing empathy among those who already have it.

What I’d love to study next is how to reach people who don’t. People who avoid these stories or who hold more exclusionary views. What kinds of messages or media could reach them? Could framing, visuals, or certain messengers make a difference? Understanding that is crucial for figuring out how to scale empathy beyond its existing audiences.

If you had to give one piece of advice to students who want to get involved in this kind of research, what would it be?

Take my class next quarter! We talk about all sorts of issues related to migration and inclusion. But seriously, get involved early. Try to work as a research assistant, even on small projects. That’s how I got started, by working under a professor who brought me into areas and questions I didn’t think I’d be interested in. Those experiences can completely change your perspective and open doors you didn’t even know existed.

Lastly, what book would you recommend for students interested in a research career in your field?

I’ve heard very good things about The Truth About Immigration by Zeke Hernandez, which is more from an economist’s perspective, and I love Rafaela Dancygier’s Dilemmas of Inclusion, which looks at the challenges left-wing parties face in Europe. They’re the parties of inclusion, but they also have to navigate tensions when the groups they’re including hold more conservative social values. It’s a really interesting read for understanding how inclusion plays out in democratic politics.

Adida’s work highlights how understanding the human side of migration through empathy and perspective-taking can lead to more inclusive policies and stronger communities worldwide.

Read More

Exploring how empathy and perspective-taking shape migration, inclusion, and public attitudes toward diversity with FSI Senior Fellow Claire Adida.

The Ripple Effects of China’s College Expansion on American Universities

China’s unprecedented expansion of higher education in 1999 increased annual college enrollment from 1 million to 9.6 million by 2020. We trace the global ripple effects of that expansion by examining its impact on US graduate education and local economies surrounding college towns. Combining administrative data from China’s college admissions system and US visa data, we leverage the centralized quota system governing Chinese college admissions for identification and present three key findings.

First, the expansion of Chinese undergraduate education drove graduate student flows to the US: every additional 100 college graduates in China led to 3.6 Chinese graduate students in the US. Second, Chinese master’s students generated positive spillovers, driving the birth of new master’s programs and increasing the number of other international and American master’s students, particularly in STEM fields. And third, the influx of international students supported local economies around college towns, raising job creation rates outside the universities, as well. Our findings highlight how domestic education policy in one country can reshape the academic and economic landscape of another through student migration and its broader spillovers.

New Book Sheds Light on Cold War Refugees in Asia

We are pleased to share the publication of a new volume, Cold War Refugees: Connected Histories of Displacement and Migration across Postcolonial Asia, edited by the Korea Program's Yumi Moon, associate professor in Stanford's Department of History.

The book, now available from Stanford University Press, revisits Cold War history by examining the identities, cultures, and agendas of the many refugees forced to flee their homes across East, Southeast, and South Asia due to the great power conflict between the US and the USSR. Moon's book draws on multilingual archival sources and presents these displaced peoples as historical actors in their own right, not mere subjects of government actions. Exploring the local, regional, and global contexts of displacement through five cases —Taiwan, Vietnam, Korea, Afghanistan, and Pakistan — this volume sheds new light on understudied aspects of Cold War history.

The book's chapters — written by Phi-Vân Nguyen, Dominic Meng-Hsuan Yang, Yumi Moon, Ijlal Muzaffar, Robert D. Crews, Sabauon Nasseri, and Aishwary Kumar — explore Vietnam's 1954 partition, refugees displaced from Zhejiang to Taiwan, North Korean refugees in South Korea from 1945–50, the Cold War legacy in Karachi, and Afghan refugees.

Purchase Cold War Refugees at www.sup.org and receive 20% off with the code MOON20.

Read More

The new volume, edited by Stanford historian Yumi Moon, examines the experiences of Asian populations displaced by the conflict between the United States and the Soviet Union.

A Little Lift in the Iron Curtain: Emigration Restrictions and Criminal Activity in Socialist East Germany

What are the consequences of selective emigration from a closed regime? To answer this question, I focus on socialist East Germany and leverage an emigration reform in 1983 that led to the departure of about 65,200 citizens. Analyzing panel data on criminal activity in a difference-in-differences framework, I demonstrate that emigration can be a double-edged sword in contexts where it is restricted. Emigration after the reform had benefits in the short run and came with an initial decline in crime. However, it created new challenges for the regime as time passed. Although the number of ordinary crimes remained lower, border-related political crimes rose sharply in later years. Analysis of emigration-related petitioning links this result to a rise in demand for emigration after the initial emigration wave. These findings highlight the complexities of managing migration flows in autocracies and reveal a key repercussion of using emigration as a safety valve.

Emil Kamalov

Encina Hall, E110

616 Jane Stanford Way

Stanford, CA 94305-6055

Emil Kamalov's research interests lie at the intersection of autocratic control, political behavior, migration, and repression, utilizing advanced quantitative methods complemented by qualitative data.

In his PhD thesis and papers, Emil develops an integrated account of extraterritorial opposition politics, examining how geopolitical tensions and host-country conditions shape emigrant activism, diaspora resilience, and migrant well-being. His findings demonstrate that under certain conditions, transnational repression by autocratic regimes can strengthen rather than weaken diaspora activism.

In collaboration with Ivetta Sergeeva, Emil co-founded and co-leads the OutRush project, the only ongoing multi-wave panel survey focusing on Russian political emigrants following Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine. The OutRush project includes over 18,000 survey observations across four waves, covering respondents from more than 100 countries. The project has garnered substantial international media coverage and has drawn attention from policymakers and experts.

Emil is expected to receive his PhD in Political and Social Sciences from the European University Institute in September 2025.