Policy Roundup: April 2023

76 Platforms v. Supreme Court with Daphne Keller (part 1)

Daphne Keller spoke with the Initiative for Digital Public Infrastructure at the University of Massachusetts Amherst about two potentially major cases currently before the Supreme Court

Policy Impact Spotlight: Marietje Schaake on Taming Underregulated Tech

Picture this: you are sitting in the kitchen of your home enjoying a drink. As you sip, you scroll through your phone, looking at the news of the day. You text a link to a news article critiquing your government’s stance on the press to a friend who works in media. Your sibling sends you a message on an encrypted service updating you on the details of their upcoming travel plans. You set a reminder on your calendar about a doctor’s appointment, then open your banking app to make sure the payment for this month’s rent was processed.

Everything about this scene is personal. Nothing about it is private.

Without your knowledge or consent, your phone has been infected with spyware. This technology makes it possible for someone to silently watch and taking careful notes about who you are, who you know, and what you’re doing. They see your files, have your contacts, and know the exact route you took home from work on any given day. They can even turn the microphone of your phone on and listen to the conversations you’re having in the room.

This is not some hypothetical, Orwellian drama, but a reality for thousands of people around the world. This kind of technology — once a capability only of the most technologically advanced governments — is now commercially available and for sale from numerous private companies who are known to sell it to state agencies and private actors alike. This total loss of privacy should worry everyone, but for human rights activists and journalists challenging authoritarian powers, it has become a matter of life and death.

The companies who develop and sell this technology are only passively accountable toward governments at best, and at worse have their tacit support. And it is this lack of regulation that Marietje Schaake, the International Policy Director at the Cyber Policy Center and International Policy Fellow at Stanford HAI, is trying to change.

Amsterdam and Tehran: A Tale of Two Elections

Schaake did not begin her professional career with the intention of becoming Europe’s “most wired politician,” as she has frequently been dubbed by the press. In many ways, her step into politics came as something of a surprise, albeit a pleasant one.

“I've always been very interested in public service and trying to improve society and the lives of others, but I ran not expecting at all that I would actually get elected,” Schaake confesses.

As a candidate on the 2008 ticket for the Democrats 66 (D66) political party of the Netherlands, Schaake saw herself as someone who could help move the party’s campaign forward, but not as a serious contender in the open party election system. But when her party performed exceptionally well, at the age of 30, Schaake landed in the third position of a 30-person list vying to fill the 25 open seats available for representatives from all political parties in the Netherlands. Having taken a top spot among a field of hundreds of candidates, she found herself on her way to being a Member of the European Parliament (MEP).

In 2009, world events collided with Schaake’s position as a newly-seated MEP. While the democratic elections in the EU were unfolding without incident, 3,000 miles away in Iran, a very different story was unfolding. Following the re-election of Mahmoud Ahmadinejad to a second term as Iran’s president, allegations of fraud and vote tampering were immediately voiced by supporters of former prime minister Mir-Hossein Mousavi, the leading candidate opposing Ahmadinejad. The protests that followed quickly morphed into the Green Movement, one of the largest sustained protest movements in Iran’s history after the Iranian Revolution of 1978 and until the protests against the death of Mahsa Amini began in September 2022.

With the protests came an increased wave of state violence against the demonstrators. While repression and intimidation are nothing new to autocratic regimes, in 2009 the proliferation of cell phones in the hands of an increasingly digitally connected population allowed citizens to document human rights abuses firsthand and beam the evidence directly from the streets of Tehran to the rest of the world in real-time.

As more and more footage poured in from the situation on the ground, Schaake, with a pre-politics background in human rights and a specific interest in civil rights, took up the case of the Green Movement as one of her first major issues in the European Parliament. She was appointed spokesperson on Iran for her political group.

![Marietje Schaake [second from the left] during a press conference on universal human rights alongside her colleauges from the European Parliament.](https://fsi9-prod.s3.us-west-1.amazonaws.com/s3fs-public/styles/680x378/public/2023-04/policy_impact_marietje_schaake_human_rights_alberto_novi_flikr_hero.png?itok=IrYo_nO9)

The Best of Tech and the Worst of Tech

But the more Schaake learned, the clearer it became that the Iranian were not the only ones using technology to stay informed about the protests. Meeting with ights defenders who had escaped from Iran to Eastern Turkey, Schaake was told anecdote after anecdote about how the Islamic Republic’s authorities were using tech to surveil, track, and censor dissenting opinions.

Investigations indicated that they were utilizing a technique referred to then as “deep packet inspection,” a system which allows the controller of a communications network to read and block information from going through, alter communications, and collect data about specific individuals. What was more, journalists revealed that many of the systems such regimes were using to perform this type of surveillance had been bought from, and were serviced by, Western companies.

For Schaake, this revelation was a turning point of her focus as a politician and the beginning of her journey into the realm of cyber policy and tech regulation.

“On the one hand, we were sharing statements urging to respect the human rights of the demonstrators. And then it turned out that European companies were the ones selling this monitoring equipment to the Iranian regime. It became immediately clear to me that if technology was to play a role in enhancing human rights and democracy, we couldn’t simply trust the market to make it so; we needed to have rules,” Schaake explained.

The Transatlantic Divide

But who writes the rules? When it comes to tech regulation, there is longstanding unease between the private and public sectors, and a different approach between the East and West shores of the Atlantic. In general, EU member countries favor oversight of the technology sector and have supported legislation like the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) and Digital Services Act to protect user privacy and digital human rights. On the other hand, major tech companies — many of them based in North America — favor the doctrine of self-regulation and frequently cite claims to intellectual property or widely-defined protections such as Section 230 as a justification for keeping government oversight at arm’s length. Efforts by governing bodies like the European Union to legislate privacy and transparency requirements are with raised hackles

It’s a feeling Schaake has encountered many times in her work. “When you talk to companies in Silicon Valley, they make it sound as if Europeans are after them and that these regulations are weapons meant to punish them,” she says.

But the need to place checks on those with power is rooted in history, not histrionics, says Schaake. Memories of living under the eye of surveillance states such as the Soviet Union and East Germany still are fresh on many European’s minds. The drive to protect privacy is as much about keeping the government in check as it is about reining in the outsized influence and power of private technology companies, Schaake asserts.

Big Brother Is Watching

In the last few years, the momentum has begun to shift.

In 2020, a joint reporting effort by The Guardian, The Washington Post, Le Monde, Proceso, and over 80 journalists at a dozen additional news outlets worked in partnership with Amnesty International and Forbidden Stories to publish the Pegasus Project, a detailed report showing that spyware from the private company NSO Group was used to target, track, and retaliate against tens of thousands journalists, activists, civil rights leaders, and even against prominent politicians around the world.

This type of surveillance has innovated quickly beyond the network monitoring undertaken by regimes like Iran in the 2000s, and taps into the most personal details of an individual’s device, data, and communications. In the absence of widespread regulation, companies like NSO Group have been able to develop commercial products with capabilities as sophisticated as state intelligence bureaus. In many cases, “no-click” infections are now possible, meaning a device can be targeted and have the spyware installed without the user ever knowing or having any suspicions that they have become a victim of covert surveillance.

![Marietje Schaake [left] moderates a panel at the 2023 Summit for Democracy with Neal Mohan, CEO of YouTube; John Scott-Railton, Senior Researcher at Citizen Lab; Avril Haines, U.S. Director of National Intelligence; and Alejandro N. Mayorkas, U.S. Secretary of Homeland Security.](https://fsi9-prod.s3.us-west-1.amazonaws.com/s3fs-public/styles/680x378/public/2023-04/policy_impact_marietje_schaake_democracy_summit_2_hero.png?itok=UXXkriBe)

“If we were to create a spectrum of harmful technologies, spyware could easily take the top position,” said Schaake, speaking as the moderator of a panel on “Countering the Misuse of Technology and the Rise of Digital Authoritarianism” at the 2023 Summit for Democracy co-hosted by U.S. President Joe Biden alongside the governments of Costa Rica, the Netherlands, Republic of Korea, and Republic of Zambia.

Revelations like those of the Pegasus Project have helped spur what Schaake believes is long-overdue action from the United States on regulating this sector of the tech world. On March 27, 2023, President Biden signed an executive order prohibiting the operational use of commercial spyware products by the United States government. It is the first time such an action has been formally taken in Washington.

For Schaake, the order is a “fantastic first step,” but she also cautions that there is still much more that needs to be done. The use of spyware made by the government is not limited by Biden's executive order, and neither is the use by individuals who can get their hands on these tools.

Human Rights vs. National Security

One of Schaake’s main concerns is the potential for governmental overreach in the pursuit of curtailing the influence of private companies.

Schaake explains, “What's interesting is that while the motivation in Europe for this kind of regulation is very much anchored in fundamental rights, in the U.S., what typically moves the needle is a call to national security, or concern for China.”

It is important to stay vigilant about how national security can become a justification for curtailing civil liberties. Writing for the Financial Times, Schaake elaborated on the potential conflict of interest the government has in regulating tech more rigorously:

“The U.S. government is right to regulate technology companies. But the proposed measures, devised through the prism of national security policy, must also pass the democracy test. After 9/11, the obsession with national security led to warrantless wiretapping and mass data collection. I back moves to curb the outsized power of technology firms large and small. But government power must not be abused.”

While Schaake hopes well-established democracies will do more to lead by example, she also acknowledges that the political will to actually step up to do so is often lacking. In principle, countries rooted in the rule of law and the principles of human rights decry the use of surveillance technology beyond their own borders. But in practice, these same governments are also sometimes customers of the surveillance industrial complex.

Schaake has been trying to make that disparity an impossible needle for nations to keep threading. For over a decade, she has called for an end to the surveillance industry and has worked on developing export controls rules for the sale of surveillance technology from Europe to other parts of the world. But while these measures make it harder for non-democratic regimes to purchase these products from the West, the legislation is still limited in its ability to keep European and Western nations from importing spyware systems like Pegasus back into the West. And for as long as that reality remains, it undermines the credibility of the EU and West as a whole, says Schaake.

Speaking at the 2023 Summit for Democracy, Schaake urged policymakers to keep the bigger picture in mind when it comes to the risks of unaccountable, ungoverned spyware industries. “We have to have a line in the sand and a limit to the use of this technology. It’s extremely important, because this is proliferating not only to governments, but also to non-state actors. This is not the world we want to live in.”

Building Momentum for the Future

Drawing those lines in the sands is crucial not just for the immediate safety and protection of individuals who have been targeted with spyware but applies to other harms of technology vis-a-vis the long-term health of democracy.

“The narrative that technology is helping people's democratic rights, or access to information, or free speech has been oversold, whereas the need to actually ensure that democratic principles govern technology companies has been underdeveloped,” Schaake argues.

While no longer an active politician, Schaake has not slowed her pace in raising awareness and contributing her expertise to policymakers trying to find ways of threading the digital needle on tech regulation. Working at the Cyber Policy Center at the Freeman Spogli Institute for International Studies (FSI), Schaake has been able to combine her experiences in European politics with her academic work in the United States against the backdrop of Silicon Valley, the home-base for many of the world’s leading technology companies and executives.

Though now half a globe away from the European Parliament, Schaake’s original motivations to improve society and people’s lives have not dimmed.

“It’s up to us to guarantee the upsides of technology and limit its downsides. That’s how we are going to best serve our democracy in this moment,” she says.

Schaake is clear-eyed about the hurdles still ahead on the road to meaningful legislation about tech transparency and human rights in digital spaces. With a highly partisan Congress in the United States and other issues like the war in Ukraine and concerns over China taking center stage, it will take time and effort to build a critical mass of political will to tackle these issues. But Biden’s executive order and the discussion of issues like digital authoritarianism at the Summit for Democracy also give Schaake hope that progress can be made.

“The bad news is we're not there yet. The good news is there's a lot of momentum for positive change and improvement, and I feel like people are beginning to understand how much it is needed.”

And for anyone ready to jump into the fray and make an impact, Schaake adds a standing invitation: “I’m always happy to grab a coffee and chat. Let’s talk!”

The complete recording of "Countering the Misuse of Technology and the Rise of Digital Authoritarianism," the panel Marietje Schaake moderated at the 2023 Summit for Democracy, is available below.

Read More

A transatlantic background and a decade of experience as a lawmaker in the European Parliament has given Marietje Schaake a unique perspective as a researcher investigating the harms technology is causing to democracy and human rights.

Surveilling the Future of American Intelligence

James Bond; Jason Bourne; Jack Bauer: cinema spies like these are the suave and daring face of spycraft and intelligence for most people.

That’s a problem, says Amy Zegart, a senior fellow at the Center for International Security and Cooperation (CISAC). In her new book, Spies Lies and Algorithms, Zegart draws on her expertise in U.S. intelligence and national security to debunk some of the pop cultural tropes around spycraft, many of which have a surprisingly pervasive influence on how both the public and policymakers understand the intelligence community.

She joins FSI Director Michael McFaul on World Class podcast to talk about the book and what she’s learned from her research about the challenges the U.S. intelligence community will need to meet in order to stay competitive in a rapidly-evolving, increasingly digital world.

Listen to the full episode now. A transcript and highlights from their conversation are available below.

Click the link for a transcript of “Spies, Lies and Algorithms with Amy Zegart."

The Origins of Spies, Lies and Algorithms

When I was a professor at UCLA, I was teaching an intelligence class. On a lark, I did a survey of my students and I asked them about their spy-themed entertainment viewing habits, as well as their attitudes towards certain intelligence topics like interrogation techniques.

What I found was there was a statistically significant correlation between their spy-themed viewing habits; people who watch the show 24 all the time were far more pro-waterboarding, among other things, than students who didn't watch spy-themed entertainment.

This got me really thinking, what do people know about espionage? Where do they get this information? And what I found is that most Americans don't know anything about the intelligence community, and when you're talking about spy agencies in a democracy, that's really problematic.

The original book was going to be more of a textbook for the class I was teaching, but as I write it, so many things started to change in the intelligence community, both politically and technologically. So with that in mind, I tried to make it forward looking to where intelligence needs to go, not just backward to where it’s been.

Who are the Spies?

The biggest surprise for me came from the research I did on open-source intelligence and nuclear threats. If ever there was an area you would think spy agencies would have cornered the market on intelligence, it would be nuclear threats.

But what I found is that there's a whole ecosystem of non-governmental people tracking nuclear threats around the world and actually uncovering really important things. That includes some open-source nuclear sleuths here at Stanford among my colleagues at CISAC.

The more I dug into this, the more I realized that open-source intelligence and publicly available data is the ballgame in the future of intelligence. Secrets still matter; but they matter a whole lot less than they did even ten years ago.

There is so much insight that we can glean from open-source information, but the intelligence community has to figure out better ways to connect with organizations and people who are in this ecosystem.

What are the Lies?

Intelligence is about deception. We don't want our enemies to understand all of our military capabilities, for example, or what our intentions are.

But I think the technology and data revolutions of the last few decades has also changed the nature of deception. It’s gone from elites deceiving elites about where their troops are, and whether they're going to attack, to mass audience deception and this disinformation-information warfare of domestic audiences like we're experiencing here in the United States.

Understanding deception, not in a pejorative sense but as an analytic frame, is critically important to being able to gather and analyze intelligence correctly.

The Power of Algorithms in Intelligence

We're drowning in data. The amount of data on Earth is estimated to double every two years. Think about that for a minute. It's just an astounding amount of data. And it's too much for any human to deal with.

So, if intelligence is in the business of collecting or finding needles in haystacks, the haystacks are growing exponentially. The intelligence community has to use artificial intelligence and other tools to augment human analysts. AI frees up analysts to then ask questions about things like intent, which humans can figure out much better than machines.

Imagine an algorithmic red team: you have humans that are developing assessments of what is Putin going to do in Ukraine, and you've got a red team that's just algorithms aggregating data, so that you have a sort of competitive analysis between humans and machines that can make the humans better. Those are the kinds of things that intelligence agencies need to be doing much more with AI.

Read More

Amy Zegart joins Michael McFaul on World Class podcast to talk about Spies, Lies and Algorithms, her new book exploring how the U.S. intelligence community needs to adapt to face a new era of intelligence challenges.

Geospatial Intelligence as a Means of Promoting International Security

In a multipolar international system during the era of technology disruption, international security continues to be fragile. Whether overtly or covertly, ambitious states have been competing to obtain a comparative advantage over the one-another, such as China and the United States. While governments rely on national technical means (NTM) on tracking other states’ actions, the implications of this competition would ultimately fall on the general population. The ubiquitous nature of international security has inspired many academic experts, private organizations, and corporations to develop open-source intelligence (OSINT) analysis with the purpose of improving transparency and expanding NTM capacities. Of the most prominent OSINT fields is geospatial intelligence and imagery analysis, which has come a long way through increased cooperation with commercial data providers, particularly satellite companies.

Over the last decade, the quality of imagery collection has increased in both spatial and temporal resolution. While the former allows for the discerning of smaller objects captured on the surface of Earth and positive identification of them, the latter allows for monitoring of sites on a daily, weekly, or monthly basis. Therefore, both are required for a comprehensive analysis of the site of interest and proper academic practice.

Over the summer, I worked with Allison Puccioni, a career imagery analyst and a consultant at BlackSky, who provided me an opportunity to cooperate with BlackSky and Planet, two of the leading commercial satellite companies on the salient issue of the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction (WMD). An article from The Drive released on July 14, 202, sparked interest in a remote facility in Xinjiang, China just south of Bosten Lake.The functionality of the facility is still disputed, but the structural features suggest that it may be a directed-energy weapons (DEW) development facility. As no previous research on this facility had been conducted, we decided to conduct a comprehensive analysis together with Allison and Katharine Leede, a senior majoring in Political Science and part of the CISAC Undergraduate Honors Program.

This analysis required the acquisition of extensive imagery of the site, which was available only at BlackSky through their global monitoring program. BlackSky was more than willing to share the imagery with us in an effort to establish academic-private sector cooperation. The data consisted of 400 images of the site spanning from mid-2019 to August 2021. To manage this large amount of data, we went through every single image, noting any key features and tracking them over time. The image below depicts an aerial view of the Bosten Lake Facility, which is characterized by the presence of large hangars with retractable roofs. The imagery is also of high temporal resolution, up to 10 images a day in some cases. This frequency allows us to create a pattern-of-life where we identified the times and days of the week the hangars would be open. Assuming that the current hypothesis is that this facility is a DEW testing site, we can infer that the tests were conducted when the hangars were open. However, further analysis is required to confirm this statement. After compiling the pattern-of-life analysis, we needed to identify the objects inside the hangars in order to confirm our hypothesis.

While BlackSky imagery has an unmatched temporal resolution, it comes at the cost of spatial resolution. Therefore, we identified key images in which activity at the site was at its highest and requested those images from Planet. Planet’s SkySat satellite constellation has a resolution of 0.5 meters, allowing one to identify small objects in the image. This technique we used is generally referred to in the intelligence community as Low-to-High Resolution Tipping and Cueing. This is the process of monitoring an area or an object of interest by a sensor and requesting “tipping” another complementary sensor platform to acquire “cueing” an image over the same area.

This project has also attracted interest from major defense-related media outlets, most notably Janes Intelligence Review (JIR). Upon completion, this project will result in a published article in JIR and is scheduled for the December 2021 edition. Additionally, the project received attention from the Defense Innovation Unit in the U.S. Department of Defense, whose representatives expressed interest in establishing cooperation for future projects.

This internship provided me an opportunity to be one of the first people to analyze an emerging case study such as the Bosten Lake Facility in China and learn how to work with commercial satellite companies. As a military officer in the Kosovar Army, I will have to deal with public-private partnerships, and the connections I have made together with the communication and networking skills I acquired will contribute to a more successful career. Additionally, geospatial intelligence analysis will be included in my job description as an intelligence officer, thus having had the chance to practice the necessary skills in both an academic and corporate setting will greatly aid me in the future.

Finally, the UNDPPA internship also allowed me to be part of the pioneering team for an environmental security project in the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK). The project was initiated as a result of negotiations between the UNDPPA and DPRK, and environmental security became the only area of mutual interest that will further facilitate cooperation from the DPRK government. As the framework for this project was only developed this summer, it is still an ongoing process requiring coordination between policymakers, diplomats, DPRK representatives, and the engineering team who realizes the requirements put forward into a platform similar to the Iraq Water Security Project. As I have had the opportunity to be present during the creation of this project, I will be looking forward to contributing to its development and seeing the result.

Arelena Shala, a student in the Class of '22 of the Ford Dorsey Master's in International Policy (MIP) helped pioneer several new projects on geospatial intelligence gathering during her summer internship with BlackSky and Planet.

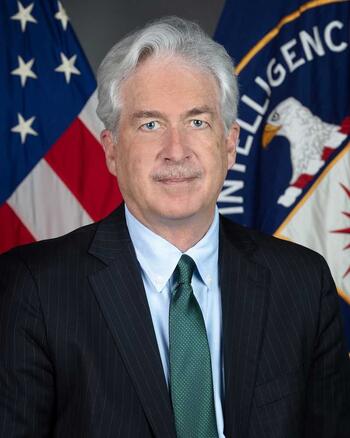

A Discussion with C.I.A. Director William Burns

For Fall Quarter 2021, FSI will be hosting hybrid events. Many events will be open to the public online via Zoom, and limited-capacity in-person attendance for Stanford affiliates may be available in accordance with Stanford’s health and safety guidelines.

| Register for Zoom (Open to the public) |

Register for In-person (Stanford affiliates only) |

The Freeman Spogli Institute for International Studies (FSI) is honored to host the Director of the Central Intelligence Agency, William J. Burns, for a discussion on the national security challenges and opportunities facing the United States, and his experiences and lessons learned during his career in the Foreign Service. FSI Director Michael McFaul will moderate the discussion and questions from the audience.

Director Burns was officially sworn in as C.I.A. Director on March 19, 2021, making him the first career diplomat to serve as Director. Director Burns holds the highest rank in the Foreign Service—Career Ambassador—and is only the second serving career diplomat in history to become Deputy Secretary of State.

Director Burns retired from the State Department U.S. Foreign Service in 2014 before becoming president of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

Director Burns is a crisis-tested public servant who spent his 33-year diplomatic career working to keep Americans safe and secure. Prior to his tenure as Deputy Secretary of State, he served as Under Secretary of State for Political Affairs from 2008 to 2011; U.S. Ambassador to Russia from 2005 to 2008; Assistant Secretary of State for Near Eastern Affairs from 2001 to 2005; and U.S. Ambassador to Jordan from 1998 to 2001. He was also Executive Secretary of the State Department and Special Assistant to former Secretaries of State Warren Christopher and Madeleine Albright; Minister-Counselor for Political Affairs at the U.S. Embassy in Moscow; Acting Director and Principal Deputy Director of the State Department’s Policy Planning Staff; and Special Assistant to the President and Senior Director for Near East and South Asian Affairs at the National Security Council.

Director Burns received three Presidential Distinguished Service Awards and the highest civilian honors from the Pentagon and the U.S. Intelligence Community. He is the author of the best-selling book, The Back Channel: A Memoir of American Diplomacy and the Case for Its Renewal (2019). He earned a bachelor’s degree in history from LaSalle University and master’s and doctoral degrees in international relations from Oxford University, where he studied as a Marshall Scholar.

Here, Right Matters - Book Talk with Alexander Vindman

For Fall Quarter 2021, FSI will be hosting hybrid events. Many events will be open to the public online via Zoom, and limited-capacity in-person attendance for Stanford affiliates may be available in accordance with Stanford’s health and safety guidelines.

Register for Zoom Register for In-Person

(Open to all) (Stanford affiliates only)

Retired U.S. Army Lieutenant Colonel Alexander Vindman, who found himself at the center of a firestorm for his decision to report the phone call between former U.S. President Donald Trump and Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky that led to presidential impeachment, tells his own story for the first time.

Here, Right Matters is a stirring account of Vindman's childhood as an immigrant growing up in New York City, his career in service of his new home on the battlefield and at the White House, and the decisions leading up to the moment of truth he faced for his nation.

Alexander Vindman, a retired U.S. Army Lieutenant Colonel, was most recently the director for Eastern Europe, the Caucasus, and Russia on the White House’s National Security Council. Previously, he served as the Political-Military Affairs Officer for Russia for the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff and as an attaché at the U.S. Embassy in Moscow, Russia. While on the Joint Staff, he co-authored the National Military Strategy Russia Annex and was the principal author for the Global Campaign for Russia. He is currently a doctoral student and fellow of the Foreign Policy Institute at the Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies (SAIS), Pritzker Military Fellow at the Lawfare Institute, and a visiting fellow at the University of Pennsylvania Perry World House. Follow him on Twitter @AVindman.

Michael Breger

Shorenstein APARC

Stanford University

Encina Hall, Room E301

Stanford, CA 94305-6055

Michael (Mike) Breger joined APARC in 2021 and serves as the Center's communications manager. He collaborates with the Center's leadership to share the work and expertise of APARC faculty and researchers with a broad audience of academics, policymakers, and industry leaders across the globe.

Michael started his career at Stanford working at Green Library, and later at the Center for Russian, East European and Eurasian Studies, serving as the event and communications coordinator. He has also worked in a variety of sales and marketing roles in Silicon Valley.

Michael holds a master's in liberal arts from Stanford University and a bachelor's in history and astronomy from the University of Virginia. A history buff and avid follower of international current events, Michael loves learning about different cultures, languages, and literatures. When he is not at work, Michael enjoys reading, painting, music, and the outdoors.

New Book by Thomas Fingar Offers Guidance to Government Appointees

As the first deputy director of national intelligence for analysis from 2005 through 2008, Shorenstein APARC Fellow Thomas Fingar had to implement legislation intended to enact sweeping reforms of intelligence procedure, establish a new federal agency, and integrate and improve the performance of 16 intelligence agencies. Synthesizing this experience, Fingar’s new book, From Mandate to Blueprint: Lessons from Intelligence Reform, explains how he carried out that tremendous charge. Identifying and codifying the commonalities that shape and constrain prospects for success, the book provides a practical guide that every new government appointee could use.

In a conversation with FSI Director Michael McFaul, Fingar discussed some of the themes and lessons he shares in the book, from prioritizing and sequencing interconnected objectives through determining organizational structures and staff arrangements, to building support and managing opposition.

“One of the first jobs of any new appointee is to determine which prescribed and suggested tasks are necessary and which ones are possible,” said Fingar. “The flip side of that is making judgments about what isn’t immediately necessary, or maybe necessary but not urgent, and what really isn’t possible under the circumstances.”

All government appointments come with a mix of tasks, responsibilities, and opportunities, and oftentimes carry with them a mandate subsuming requirements and authorities, but virtually never do they come with a blueprint detailing the steps to achieve the required and desirable changes over a four-year time horizon.

When Fingar accepted the position of deputy director of national intelligence for analysis, he knew he had to implement the legislative and presidential mandate he was going to be judged by — namely, the Intelligence Reform and Terrorism Prevention Act of 2004, which President George W. Bush signed into law in December 2004 — and to meet the ongoing intelligence responsibilities amid reforming and reorienting the organization. But he also prioritized another necessary task, that of restoring confidence in the intelligence community.

After the events of September 11, 2001 and the failure to discover weapons of mass destruction in Iraq, the intelligence community faced severe criticism and harsh scrutiny. “The loss of confidence began at the top, with President Bush,” said Fingar, “and went down through Congress and senior officials, influencing the morale of the workforce.” He knew that it was impossible to meet the requirements of the mission if the people supported by it did not have confidence.

Next-step considerations must address whether the requisite conditions to achieve the prioritized objectives — including staff, information, authorities, and funding — exist or must be obtained. For example, if some tasks require skills that are not currently available, then it is essential to identify and recruit people with the necessary skills and experience. Or if building the capacity to achieve priority goals requires organization restructuring and personnel reassigning, then these tasks require steps to protect or deemphasize legacy activities.

To succeed in their roles, government appointees must also win cooperation and stave off criticism both from opponents and those who believe they could do better. That, in turn, requires one to strike a balance between transparency and flexibility. Knowing what to report and when to report it, having a vision that is clear and easy to explain, and responding to feedback while still conveying an image of resolution and handle on strategy are all invaluable for judgments about what steps to continue, modify, or jettison right away, Fingar writes in his book.

“We captured this with a motto that was also our modus operandi,” he said. "Think Big. Start Small. Fail Cheap. Fix Fast. Listen to feedback. Involve people in the decision-making process.”

Thomas Fingar, Shorenstein APARC Fellow at FSI

Read More

Drawing on his experience implementing one of the most comprehensive reforms to the national security establishment, APARC Fellow Thomas Fingar provides newly appointed government officials with a practical guide for translating mandates into attainable mission objectives.