Global Health at a Crossroads

The world’s health systems face a complex and interconnected set of challenges that threaten to outpace our capacity to respond. Geopolitical fragmentation, climatic breakdown, technological disruption, pandemic threats, and misinformation have converged to strain the foundations of global health. Building resilient global health systems requires five urgent reforms: sharpening the mandate of the World Health Organization (WHO), operationalizing the One Health concept, modernizing procurement, addressing the climate–health nexus, and mobilizing innovative financing. Together, these shifts can move the world from fragmented, reactive crisis management to proactive, equitable, and sustainable health security.

Emerging and Escalating Threats

While the global community demonstrated remarkable resilience in weathering the COVID-19 pandemic, the crisis also exposed profound structural weaknesses in global health governance and architecture. Chronic underinvestment in health systems led to coverage gaps, workforce shortages, and inadequate surveillance systems. The pandemic also revealed a fragmented global health architecture, plagued by institutional silos among key agencies (Elnaiem et al. 2023).

Years later, the aftershocks of the pandemic still resonate worldwide, with the ongoing triple burden of disease—the unfinished agenda of maternal and child health, the rising silent pandemic of noncommunicable diseases, and the reemergence of communicable diseases. These challenges, combined with the persistent challenge of malnutrition, unmet needs in early childhood development, growing concerns around mental health, and the threat of other emerging diseases, as well as the rising toll of trauma, injury, and aging populations, have placed countries across the world under immense strain. Health systems face acute infrastructure gaps, critical workforce shortages, and persistent inequities in service delivery, making it increasingly difficult to address the complex and evolving health needs of their populations. Post-pandemic fiscal tightening has constrained health budgets with debt-to-GDP ratios exceeding 70–80% in parts of the region (UN ESCAP 2023).

Furthermore, climate change is fundamentally redefining the risk landscape. Rising temperatures, more frequent floods, intensifying storms, and shifting vector ranges for organisms like mosquitoes and ticks are disrupting food systems, displacing populations, and driving new patterns of disease transmission. Over the next 25 years in low- and middle-income countries, climate change could cause over 15 million excess deaths, and economic losses related to health risks from climate change could surpass $20.8 trillion (World Bank 2024). The cost of inaction has never been higher.

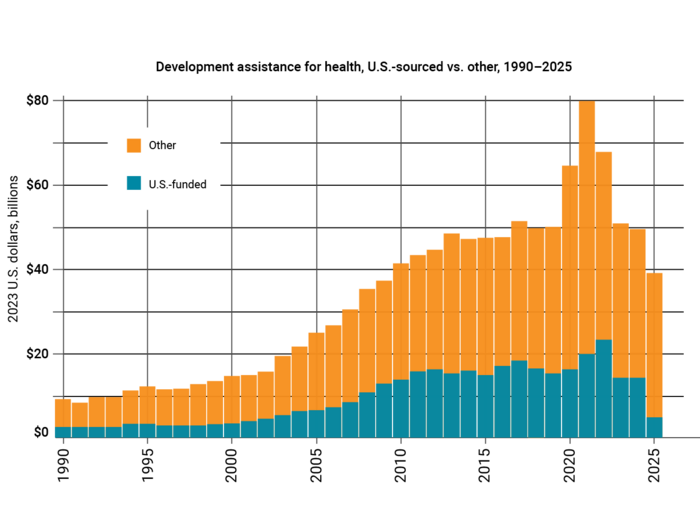

Meanwhile, deepening political polarization is amplifying conflict and weakening the global cooperation essential for scientific progress. The number of geopolitical disturbances worldwide is at an all-time high, displacing over 122 million people and eroding access to essential health services (UNHCR 2024). In 2023, false and conspiratorial health claims amassed over 4 billion views across digital platforms, compromising vaccine uptake and fueling health-related conspiracy theories. (Kisa and Kisa 2025). Furthermore, exponential technological advances in artificial intelligence are outpacing public health governance systems, creating new ethical and equity dilemmas. Global development assistance for health has significantly declined by more than $10 billion, with sharp cuts driven by the United States. This decline is likely to continue over the next five years (Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation 2025).

Note: Development assistance for health is measured in 2023 real US dollars; 2025 data are preliminary estimates.

Source: Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation 2025.

Sign up for APARC newsletters to receive our experts' updates >

Five Critical Reform Directions for Future-Proofing Global Health Systems

1. WHO matters more than ever — but only if it sharpens its focus.

The World Health Organization remains the technical backbone of global health, with a mandate to set norms and standards, shape research agendas, monitor health trends, coordinate emergency responses and regulation, and provide technical assistance. COVID-19 underscored both its indispensability and its limitations. During the pandemic, WHO convened states, disseminated guidance, and spearheaded initiatives like the Solidarity Trial and COVAX to promote vaccine equity, illustrating why it remains vital as the only neutral platform where 194 member states can cooperate on pandemics, antimicrobial resistance, or climate-related health risks. Its work on universal health coverage, the “triple burden” of disease, and global health data continues to anchor policy across countries.

At the same time, the crisis exposed structural weaknesses: WHO lacks enforcement authority, relies heavily on voluntary donor-driven funding, and sometimes stretches beyond its comparative strengths. When it shifts from convening and technical guidance into direct fund management, logistics, or large-scale program delivery, it risks diluting its mandate and eroding trust. Critics argue this reflects a broader challenge of an expansive mandate and donor-driven mission creep, pushing WHO beyond what 7,000 staff and a modest budget can realistically deliver. The way forward lies in sharpening focus: leveraging its convening power and legitimacy, providing technical expertise and evidence-based guidance, coordinating emergencies under the International Health Regulations, and advocating for equity in access to medicines and care. Anchored in these core strengths, a more agile WHO can better lead during crises, sustain credibility, and ensure that global health standards are consistently applied across diverse national contexts.

2. Animal Health as the Next Frontier

More than 70 percent of emerging infectious diseases are zoonotic in origin, with roughly three-quarters of newly detected pathogens in recent decades spilling over from animals into humans (WHO 2022; Jones, Patel, Levy, et al. 2008). The economic costs are staggering: the World Bank estimates that zoonotic outbreaks have cost the global economy over $120 billion between 1997 and 2009 through crises such as Nipah, SARS, H5N1, and H1N1 (World Bank 2012). The drivers of spillover are intensifying due to deforestation and land-use change, industrial livestock farming, wildlife trade, and climate change. These are further accelerating the emergence of novel pathogens.

However, the governance of animal health remains fragmented. While WHO, the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), and the World Organization for Animal Health (WOAH) each hold mandates, they often operate in silos. The Quadripartite, expanded in 2021 to include the United Nations Environment Programme, launched a One Health Joint Plan of Action (2022–26), but it remains underfunded and lacks strong political commitment.

There is an urgent need to move One Health from principle to practice. To fill this governance gap, the world should consider establishing an independent intergovernmental alliance for animal health with a clear mandate. This could strengthen global One Health response by augmenting joint surveillance, building veterinary workforce capacity, and integrating environmental data into early warning systems. Such an alliance should avoid creating new bureaucratic layers and instead leverage the Quadripartite as its operational backbone. Embedding One Health into national health strategies and cross-sectoral policies would enable animal, human, and environmental health systems to work in tandem and address risks at their source. Preventive investments are also very cost-effective; the World Bank estimates that annual One Health prevention investments of $10–11 billion could save multiple times that amount in avoided pandemic losses (World Bank 2012). Strengthening One Health is both a health and economic necessity.

3. Agile Procurement: The Missing Link in Global Health Security

COVID-19 revealed how vital procurement and financial management are to global health security. A system built for routine procurement was suddenly called upon to handle crisis response on a worldwide scale, and it struggled to keep up. When vaccines became available, strict procedures, fragmented supply chains, and export restrictions meant access was uneven and often delayed. Developed countries’ advance purchase agreements stockpiled most of the supply, leaving many low- and middle-income countries waiting for doses. Within the UN system and its partners, overly complex procurement rules slowed the speed to market, and the lack of harmonized regulatory recognition caused further delays. As a result, those least able to handle shocks faced the longest waits and highest costs.

Reform must begin by making procurement agile, transparent, and equitable. Emergency playbooks should be pre-cleared to ensure that indemnity clauses and quality assurance requirements can be activated immediately when the next crisis arises. Regional pooled procurement mechanisms, like the Pan American Health Organization’s Revolving Fund or the African Union’s pooled initiatives, should be expanded to diversify supply sources and anchor distributed manufacturing. End-to-end e-procurement platforms would provide real-time shipment tracking, facility-level stock visibility, and open dashboards to strengthen accountability. Financial management must be integrated with procurement so that contingency funds, countercyclical reserves, and fast-disbursing credit lines can release resources in tandem with purchase orders. Together, these reforms would ensure that in future health emergencies, these procurement systems act as lifelines rather than bottlenecks.

4. Addressing the Health–Climate Nexus

Climate change poses severe health risks, disproportionately affecting women and vulnerable populations in developing countries through heatwaves, poor air quality, food and water insecurity, and the spread of infectious diseases. Climate-related disasters are increasing in frequency and severity worldwide, reshaping both economies and health systems. In 2022, there were 308 climate-related disasters worldwide, ranging from floods and storms to droughts and wildfires (ADRC 2022). These events generated an estimated $270 billion in overall economic losses, with only about $120 billion insured—underscoring the disproportionate burden on low- and middle-income countries where resilience and coverage remain limited (Munich Re 2023). Over the past two decades, Asia and the Pacific have consistently been the most disaster-prone regions, accounting for nearly 40% of all global events, but every continent is now affected, from prolonged droughts in Africa and mega storms in North America to record-breaking heatwaves in Europe (UNEP n.d.).

Meeting this challenge requires a dual agenda of adaptation and mitigation. Health systems must be made climate-resilient by hardening infrastructure against floods and storms, ensuring reliable, clean energy in clinics and hospitals, and building climate-informed surveillance and early-warning systems that can anticipate disease outbreaks linked to environmental change. Supply chains need redundancy and flexibility to withstand shocks, and frontline workers require training to manage climate-driven health crises. At the same time, health systems must rapidly decarbonize. This means greening procurement and supply chains, phasing out high-emission medical products like certain inhalers and anesthetic gases, upgrading buildings and transport fleets, and embedding sustainability into financing and governance. Momentum is growing. The 2023 G20 Summit in Delhi, supported by the Asian Development Bank (ADB), recognized the health–climate nexus as a global priority, and institutions such as WHO, the World Bank, and ADB have begun to advance this agenda. The next step is to translate commitments into operational change by embedding climate-health strategies into national health plans, financing frameworks, and cross-sectoral policies. Climate action, sustainability, and resilience need to be integrated into the foundation of health systems.

5. Mobilizing Innovative Financing

Strengthening health systems and preventing future pandemics will require massive financing, but global health funding is in decline. Innovative mechanisms to mobilize new resources are essential. This requires stronger engagement with finance ministries, development financing institutions, and the private sector to design models that attract and de-risk investment while enabling rapid disbursement during emergencies. International financing institutions (IFIs) need to unlock innovative financial pathways to amplify health investments. They need to deploy blended finance initiatives, public-private partnerships, guarantees, debt swaps, and outcome-based financing tools to mobilize private capital for health. Over the past few years, IFIs have committed billions in health-related financing worldwide. This has included landmark support for vaccine access facilities, delivery of hundreds of millions of COVID-19 vaccine doses, and mobilization of large-scale response packages that combine grants, loans, and technical assistance.

There is a need to broaden the financing mandate beyond investing in universal health coverage and mobilize capital for emerging areas, including the climate-health nexus, mental health, nutrition, rapid urbanization, demographic shifts, digitization, and non-communicable diseases. By leveraging their balance sheets, IFIs can generate a multiplier effect in fund mobilization and attract new financing actors. Innovative instruments are already demonstrating potential. For example, the International Finance Facility for Immunisation (IFFIm), which issues “vaccine bonds” backed by donor pledges, has raised over $8 billion for Gavi immunization programs (IFFIm 2022; Moody’s 2024). Debt-for-health and debt-for-nature swaps have redirected debt service into social outcomes. For example, El Salvador’s 2019 Debt2Health agreement with Germany channeled approximately $11 million into strengthening its health system, while Seychelles’ debt-for-nature swap created SeyCCAT to finance marine conservation, yielding social and resilience co-benefits for coastal communities (Hu, Wang, Zhou, et al. 2024). Similarly, contingent financing facilities—such as the Innovative Finance Facility for Climate in Asia and the Pacific (IF-CAP) and the International Financing Facility for Education (IFFEd)—also hold significant potential for health (IFFEd n.d.; ADB n.d.). These examples demonstrate how contingent financing and swaps can expand fiscal space without exacerbating debt distress.

This can create a virtuous cycle of facilitating investments that create regional cooperation for sustainable and scalable impact. In this vein, the G20 Pandemic Fund is a beacon of catalytic multilateralism funding in a fragmented world. Launched in 2022 with over $2 billion pooled from governments, philanthropies, and multilaterals, it strengthens pandemic preparedness in low- and middle-income countries. Every $1 awarded from the Pandemic Fund has mobilized an estimated $7 in additional financing. The fund demonstrates that nations can still unite around shared threats, offering hope and a template for collective action on global challenges.

Equally important is the ability to deploy funds rapidly in emergencies. During the COVID-19 pandemic, reserve and countercyclical funds, used by countries such as Germany, the Netherlands, and Lithuania, along with the Multilateral Development Bank’s fast-track financing facilities with streamlined approval and disbursement processes, provided urgent and timely financing support (Sagan, Webb, Azzopardi-Muscat, et al. 2021; Lee and Aboneaaj 2021). These mechanisms should be institutionalized in national financial management systems as well as IFIs to ensure rapid funding disbursement in future health emergencies

Moving Forward

Delivering on this reform agenda requires more than technical fixes—it demands political will, sustained financing, and cross-sectoral collaboration. Member states must empower WHO to lead within its comparative strengths, while reinforcing One Health through stronger mandates and funding. Governments, IFIs, and the private sector should jointly design agile procurement and financing mechanisms that can be activated at speed during crises. Embedding health into climate policies and climate resilience into health strategies will ensure that future systems are both sustainable and resilient to shocks. Above all, reform efforts must be anchored in equity, so that the most vulnerable are protected first.

The opportunity before the global community is to reimagine health as the backbone of resilience and prosperity in the 21st century. A whole-of-systems approach is necessary to clarify mandates, integrate animal and environmental health, develop agile and fair procurement systems, embed climate action into health systems, and mobilize innovative financing. The steps taken in the next few years can lead to a more connected, cooperative, and future-ready global health architecture.

Works Cited

ADB (Asia Development Bank). n.d. “IF-CAP: innovative Finance Facility for Climate in Asia and the Pacific.”

ADRC (Asian Disaster Reduction Center). Natural Disasters Data Book 2022.

Elnaiem, Azza, Olaa Mohamed-Ahmed, Alimuddin Zumla, et al. 2023. “Global and Regional Governance of One Health and Implications for Global Health Security.” The Lancet 401 (10377): 688–704.

Hu, Yunxuan, Zhebin Wang, Shuduo Zhou, et al. 2024. “Redefining Debt-to-Health, a Triple-Win Health Financing Instrument in Global Health.” Globalization and Health 20 (1): 39.

Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation. 2025. “Financing Global Health.”

IFFEd (International Financing Facility for Education). n.d. “A Generation of Possibilities.”

IFFIm (International Finance Facility for Immunisation). 2022. “How the World Bank Built Trust in Vaccine Bonds.” October 21.

Jones, Kate E., Nikkita G. Patel, Marc A. Levy, et al. 2008. “Global Trends in Emerging Infectious Diseases.” Nature 451: 990–93.

Kisa, Adnan, and Sezer Kisa. 2025. “Health Conspiracy Theories: A Scoping Review of Drivers, Impacts, and Countermeasures.” International Journal for Equity in Health 24 (1): 93.

Lee, Nancy, and Rakan Aboneaaj. 2021. “MDB COVID-19 Crisis Response: Where Did the Money Go?” CGD Note, Center for Global Development, November.

Moody’s. 2024. "International Finance Facility for Immunisation—Aa1 Stable” Credit opinion. October 29.

Munich Re. 2023. “Climate Change and La Niña Driving Losses: The Natural Disaster Figures for 2022.” January 10.

Sagan, Anna, Erin Webb, Natasha Azzopardi-Muscat, et al. 2021. Health Systems Resilience During COVID-19: Lessons for Building Back Better. World Health Organization and the European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies.

UN ESCAP (United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific). 2023. “Public Debt Dashboard.”

UNEP (United Nations Environment Programme). n.d. “Building Resilience to Disasters and Conflicts.” Accessed September 1, 2025.

UNHCR (United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees). 2024. Global Trends Report. Copenhagen, Denmark.

WHO (World Health Organization). 2022. Zoonoses and the Environment.

World Bank. 2012. People, Pathogens and Our Planet: The Economics of One Health.

World Bank. 2024. The Cost of Inaction: Quantifying the Impact of Climate Change on Health in Low- and Middle-Income Countries. Washington D.C.

Read More

Why Now Is the Time for Fundamental Reform

![[Left to right]: Emerson Johnston, Tiffany Saade, Chan Leem](https://fsi9-prod.s3.us-west-1.amazonaws.com/s3fs-public/styles/727x409/public/2025-03/cybernetica.jpg?h=71976bb4&itok=f3lwJ11Y)

![[Left to right]: Julia Ilhardt, Serena Rivera-Korver, Johanna von der Leyen, and Michael Alisky](https://fsi9-prod.s3.us-west-1.amazonaws.com/s3fs-public/styles/727x409/public/2025-03/gerhub.jpg?h=71976bb4&itok=ncTsPzeE)

![[Left to right]: Euysun Hwang, Sakeena Razick, Leticia Lie, and Julie Tamura](https://fsi9-prod.s3.us-west-1.amazonaws.com/s3fs-public/styles/727x409/public/2025-03/disinfo_ghana.jpg?h=71976bb4&itok=m0iXK4Et)

![[Left to right]: Samara Nassor, Gustavs Zilgalvis, and Helen Phillips](https://fsi9-prod.s3.us-west-1.amazonaws.com/s3fs-public/styles/727x409/public/2025-03/aus_space.jpg?h=0d03432e&itok=CHIkKqEP)

![[Left to right]: Sandeep Abraham, Sabina Nong, Kevin Klyman, and Emily Capstick](https://fsi9-prod.s3.us-west-1.amazonaws.com/s3fs-public/styles/727x409/public/2025-03/digital_futures_lab.jpg?h=71976bb4&itok=irALsTsT)

![[Left to right]: Alex Bue, Rachel Desch, and Marco Baeza](https://fsi9-prod.s3.us-west-1.amazonaws.com/s3fs-public/styles/727x409/public/2025-03/cdd_ghana.jpg?h=71976bb4&itok=zmf6_ARg)