Organizing from Within: Defining and Classifying Police-Led Armed Groups in Rio de Janeiro

Organizing from Within: Defining and Classifying Police-Led Armed Groups in Rio de Janeiro

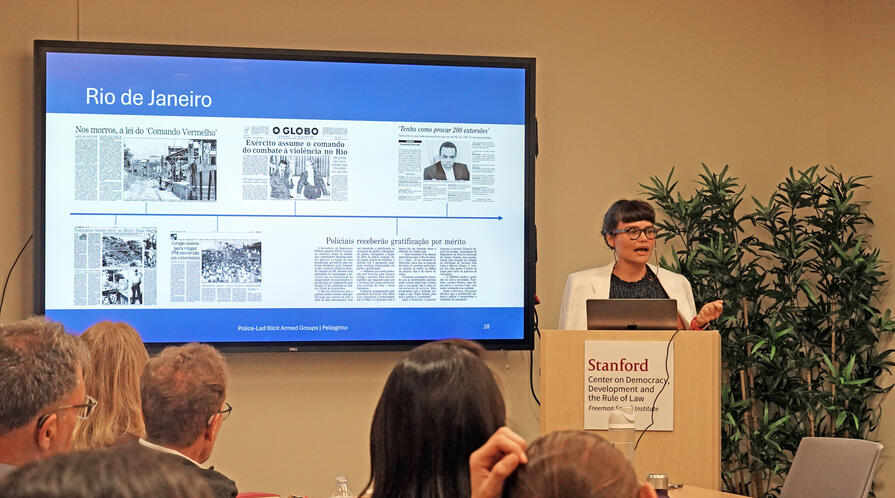

Gerhard Casper Postdoctoral Fellow Ana Paula Pellegrino presented her research on police-led armed illicit groups in Brazil, exploring what distinguishes them and the conditions that enable their formation.

In a CDDRL research seminar held on November 20, 2025, Gerhard Casper Postdoctoral Fellow Ana Paula Pellegrino presented her research on the emergence of police-led armed illicit groups (PLAIGs) in Brazil. Pellegrino defines them as illicit organizations with coercive capacity led by active-duty police officers. Her seminar explored what makes these groups distinctive, why they form, and the conditions that allow them to take shape.

As discussed by Pellegrino, unlike ordinary corruption, informal protection rackets, or gangs that employ off-duty police as security, PLAIGs are fully organized and independently governed armed groups that operate illicitly, possess their own coercive capacity, and are led by active-duty police officers who remain part of the state. Because of this unique position inside the public safety apparatus, these groups can draw on the authority and resources of the state, becoming spoilers of efforts to monopolize violence.

To better understand how these groups arise, Pellegrino examines both the motivations behind their formation and the conditions that enable them. She argues that officers create these groups primarily as a rent-extraction strategy when they perceive the costs of policing to be rising, typically in response to a growing armed threat. As violence escalates, both politicians and the police feel pressure: politicians face public demands for safety, while officers face greater personal danger on the ground. This imbalance produces frustration within the police ranks and motivates some officers to exploit their coercive capacity for profit.

However, motivation alone is not enough, as the opportunity to form PLAIGs depends on two enabling conditions. First, police must have greater coercive capacity than the threat they face, allowing them to compete with or expel armed groups. Second, they must have sufficient discretion to use their capacity outside of official duties. Pellegrino emphasizes that this autonomy is shaped by the degree of political control over police. When oversight is strong, officers cannot use state resources to build private organizations. When oversight is weak, however, officers have both the means and the opportunity to organize. Pellegrino refers to this dynamic as the Warrior’s Paradox: the increased investment in police capacity meant to combat disorder also creates the conditions for police to generate disorder themselves.

To test her argument, Pellegrino draws on extensive process tracing and three years of fieldwork in Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo. Despite similar histories of police violence, only Rio developed PLAIGs. Pellegrino shows that Rio consistently expanded police coercive power while failing to impose meaningful oversight, creating the conditions for PLAIGs to flourish after the rise of the Red Command and the Third Command of the Capital, prison gangs turned drug trade organizations. São Paulo, by contrast, implemented institutional reforms in the 1990s and early 2000s that tightened accountability, standardized use-of-force rules, and constrained police discretion, even after the rise of the First Command of the Capital, an equally powerful drug trade organization. As a result, officers in São Paulo lacked the autonomy and impunity necessary to form armed organizations.

Pellegrino closed by emphasizing that PLAIGs emerge not from state weakness but from well-equipped police forces operating with insufficient oversight, enabling officers to convert state authority into private coercive power. This, she claims, illustrates how police can become actors who undermine, rather than protect, the state’s monopoly of violence.