The Fragility of Democratic Revolutions: Why Counterrevolutions Emerge and Succeed

The Fragility of Democratic Revolutions: Why Counterrevolutions Emerge and Succeed

Georgetown political scientist Killian Clarke argues that unarmed, democratic revolutions are uniquely vulnerable to reversal, not because they lack legitimacy or popular support, but because of the kinds of power resources they rely on and later abandon.

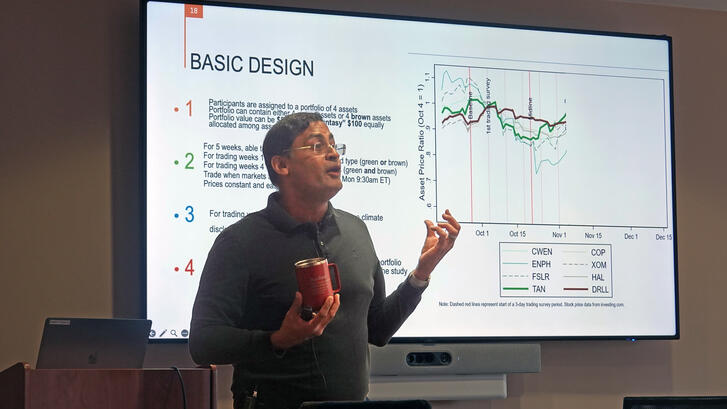

At a CDDRL seminar held on November 7, 2025, Georgetown political scientist Killian Clarke presented new research on why some revolutions consolidate into lasting political change while others are reversed through counterrevolution. His central claim is that unarmed, democratic revolutions are uniquely vulnerable to reversal, not because they lack legitimacy or popular support, but because of the kinds of power resources they rely on and later abandon. Drawing on a global dataset of 114 revolutions since 1900, Clarke showed that nearly one in three democratic revolutions is later overthrown, a rate dramatically higher than that of leftist or ethno-nationalist revolutions. Still, two-thirds of democratic revolutions do survive, raising questions about how so many of them manage to resist counterrevolution despite their weaknesses.

Clarke defines counterrevolution as the restoration of a version of the old regime after a successful revolution, whether through coups, elite realignments, or mass-backed reversals. His explanation centers on the resource asymmetries that distinguish unarmed, democratic revolutions from their violent counterparts. Whereas Marxist, nationalist, or armed uprisings build coercive capacity, external alliances, and strong organizational hierarchies, democratic revolutions typically succeed through broad, decentralized, and nonviolent mass mobilization. This allows them to topple entrenched autocrats, but leaves them without reliable security forces or disciplined party structures once in power. The feature that makes them strong during the uprising — large numbers in the streets — becomes a source of fragility once governing begins.

The mechanism Clarke traces is one of post-revolutionary demobilization. After seizing power, new democratic leaders often pivot toward institutional governance, suppressing further street mobilization in the name of stability. But this demobilization fragments the revolutionary coalition and removes the only leverage it holds over old-regime actors — societal pressure. When the coalition fractures, counterrevolutionary elites can reenter the arena with support from military, foreign patrons, or disillusioned factions of the original movement.

Egypt’s 2011 revolution illustrates this pattern. The mass uprising that ousted Hosni Mubarak briefly held the military at bay through continued mobilization. But once elected, President Mohamed Morsi of the Muslim Brotherhood tried to govern by appeasing the military and old regime elites, sidelining secular allies, and discouraging protest. But popular mobilization never really declined; instead, it transformed, and eventually came to be directed not in defense of the revolution but against the Morsi government, ultimately enabling the 2013 coup. Clarke emphasized that Egypt did not fall because counterrevolutionaries grew powerful, but because revolutionaries abandoned the mobilizational strategy that had given them power in the first place.

Clarke then compared Egypt's counterrevolutionary outcome to Venezuela's 1958 revolution, another unarmed, democratic revolution against a military government. By contrast, Venezuela’s 1958 democratic transition succeeded because revolutionary leaders remobilized supporters when a military countercoup emerged, bringing hundreds of thousands into the streets and forcing the generals to retreat. In Clarke’s view, Venezuela shows that democratic revolutions can survive, but only when leaders treat post-revolutionary politics as a continuation of the struggle against the old regime.

Clarke concluded by noting a long-term decline in successful counterrevolutions during the late 20th century, followed by a possible uptick in the 2010s. The return of multipolar geopolitical backing for authoritarian restoration — and the global spread of unarmed, democratic revolutions — may be recreating the conditions under which counterrevolutions thrive.