Empowering the World: Entrepreneurship and the Future of Foreign Policy

Please note: the start time for this event has been moved from 3:00 to 3:15pm.

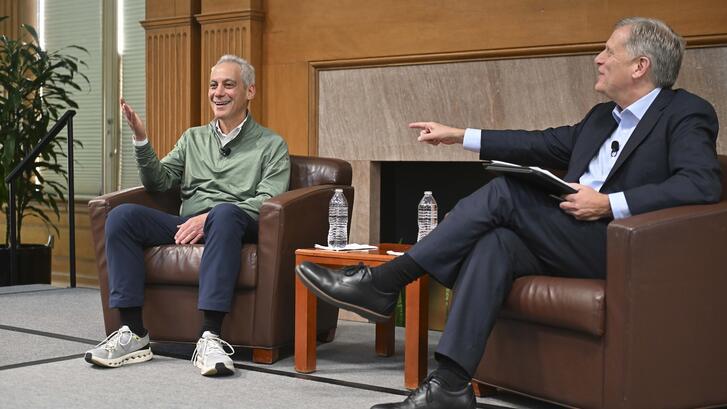

Join FSI Director Michael McFaul in conversation with Richard Stengel, Under Secretary of State for Public Diplomacy and Public Affairs. They will address the role of entrepreneurship in creating stable, prosperous societies around the world.

Michael A. McFaul

Encina Hall

616 Jane Stanford Way

Stanford, CA 94305-6055

Michael McFaul is the Ken Olivier and Angela Nomellini Professor of International Studies in Political Science, Senior Fellow at the Freeman Spogli Institute for International Studies, and the Peter and Helen Bing Senior Fellow at the Hoover Institution, all at Stanford University. He joined the Stanford faculty in 1995 and served as FSI Director from 2015 to 2025. He is also an international affairs analyst for MSNOW.

McFaul served for five years in the Obama administration, first as Special Assistant to the President and Senior Director for Russian and Eurasian Affairs at the National Security Council at the White House (2009-2012), and then as U.S. Ambassador to the Russian Federation (2012-2014).

McFaul has authored ten books and edited several others, including, most recently, Autocrats vs. Democrats: China, Russia, America, and the New Global Disorder, as well as From Cold War to Hot Peace: An American Ambassador in Putin’s Russia, (a New York Times bestseller) Advancing Democracy Abroad: Why We Should, How We Can; and Russia’s Unfinished Revolution: Political Change from Gorbachev to Putin.

He is a recipient of numerous awards, including an honorary PhD from Montana State University; the Order for Merits to Lithuania from President Gitanas Nausea of Lithuania; Order of Merit of Third Degree from President Volodymyr Zelenskyy of Ukraine, and the Dean’s Award for Distinguished Teaching at Stanford University. In 2015, he was the Distinguished Mingde Faculty Fellow at the Stanford Center at Peking University.

McFaul was born and raised in Montana. He received his B.A. in International Relations and Slavic Languages and his M.A. in Soviet and East European Studies from Stanford University in 1986. As a Rhodes Scholar, he completed his D. Phil. in International Relations at Oxford University in 1991.