Polish Presidential Election 2020: Two Months Out

Polish Presidential Election 2020: Two Months Out

For a broader look at the upcoming Polish election, its stakes and major figures, see our scene-setter.

On May 10, 2020 Polish voters will head to the polls for the first round of Poland’s presidential election. SIO has been following key narratives across Facebook Pages and Groups in order to get a better understanding of the role of social media in this important European election. In this post we compare candidate coverage on mainstream Polish news outlets’ Facebook Pages to the larger Facebook landscape. We observe that content related to far-right candidates makes up a greater percentage of general Facebook content than of content on mainstream outlets’ Pages, and that this greater portion is matched by greater engagement. There are several ways to interpret this. On the one hand, the mainstream media may be reluctant to give far-right candidates press, and thus their coverage may not reflect the candidates’ true level of support among the electorate. On the other hand, there is evidence that far-right Pages have been especially successful in boosting engagement on Facebook—often by posting content simultaneously across networks of Pages. To this end, we show how one far-right network uses 17 Pages and a handful of content farms to boost its candidate in the election.

Poland has a two-round presidential election; the first vote on May 10 will determine which two candidates advance to the second round on May 24, unless one candidate receives an absolute majority (in which case, he or she will be declared the victor). The frontrunner, incumbent President Andrzej Duda of the PiS (Law and Justice) party, has reached the 50% mark in only one opinion poll, making a second round quite likely. Polls have tightened in recent weeks, suggesting that Duda’s main rivals—Małgorzata Kidawa-Błońska of the centrist Civic Platform (Platforma Obywatelska, or PO), Władysław Kosiniak-Kamysz of the Christian-Democratic Polish People’s Party (Polskie Stronnictwo Ludowe, or PSL), and independent candidate Szymon Hołownia—have a better chance at surpassing Duda than was previously thought. Several polls show that a second round election between Duda and one of his rivals could come down to just a few percentage points. (Other polls from mid-February, on the other hand, suggest that Duda’s lead is relatively safe).

Political Narratives on Facebook

Within this political environment, Facebook plays an increasingly important role. According to Statista, over 1.5 million Poles have joined Facebook in the last year, and spending on political ads—while capped at 19.4 million PLN by Polish law—continues to rise on Facebook.

To better understand how the Polish citizen-driven political landscape on Facebook compares to that of more traditional political media in Poland—such as newspapers, magazines, and television—we compared political content on a set of diverse Polish “mainstream media” Facebook Pages to political content across Facebook.1 We collected posts that mentioned the presidential candidates, limiting posts to those that were written in Polish, and including searches for all the grammatical cases in which the candidates’ names could appear.

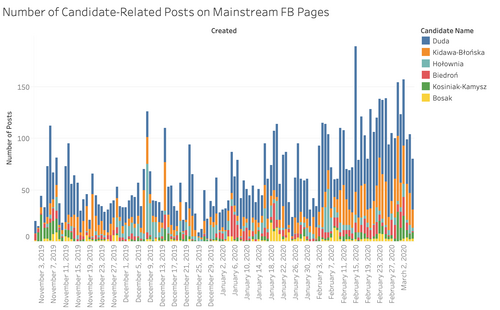

Number of Facebook posts referring to candidates’ names by day from Nov 1, 2019—the week after parliamentary elections were held—to March 5, 2020, on Polish “mainstream” media Pages. Data courtesy of CrowdTangle.

The results for Polish “mainstream media” Pages are not surprising and generally track with polling: Duda, both a 2020 candidate and the sitting president, receives substantially more coverage than any other candidate; but the amount of content referring to other candidates has increased in recent months as well. Duda’s principal rival, Małgorzata Kidawa-Błońska, receives the second most mentions, followed by Hołownia, Biedroń, Kosiniak-Kamysz, and Bosak, in that order.2 There are visible spikes on the days when candidates entered the race: Dec 8 (Hołownia), Dec 14 (Kidawa-Błońska), and Jan 18 (Bosak).

The picture on Facebook more broadly—including, but not limited to, the “mainstream media” Pages—looks somewhat different.

Number of Facebook posts referring to candidates’ names by day from Nov 1, 2019 to March 5, 2020 across all Pages and Groups visible to CrowdTangle. Data courtesy of CrowdTangle.

Duda and Kidawa-Błońska remain in the two top positions, in terms of total mentions, but there are changes below them: in particular, the far-right candidate from Konfederacja, Krzysztof Bosak, jumps from sixth to third. This suggests that the far right is better represented across Facebook than in Polish “mainstream” media Facebook Pages.

One could object that these are just mention totals, and that this does not indicate that users are actually engaging with the content. Perhaps Bosak-aligned Pages are simply spinning up content irrespective of engagement. As the figure below shows, however, Bosak remains in third when we add up the total interactions—like, love, angry, wow, etc.—that posts referring to candidates receive. The far-right candidate does consistently better in terms of drawing reactions from Facebook users than the other three low-polling candidates:

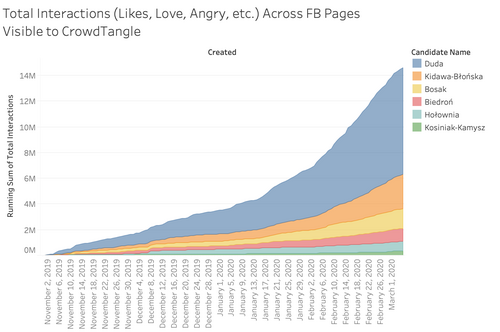

Running sum of interactions on Posts referring to candidates’ names from Nov 1, 2019 to March 5, 2020 across all Pages and Groups visible to CrowdTangle. Data courtesy of CrowdTangle.

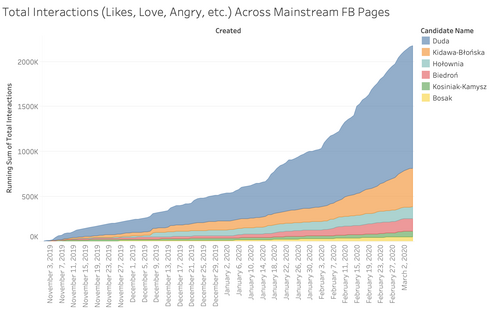

This is not true of candidate-related content on Polish “mainstream media” Facebook Pages, where the enthusiasm of Bosak’s and Biedroń’s supporters does not seem to compensate for the mainstream Pages’ tendency to publish about them less often:

Running sum of interactions on Posts referring to candidates’ names from Nov 1, 2019 to March 5, 2020 across “mainstream” Pages. Data courtesy of CrowdTangle.

The fact that Bosak-related (i.e., far-right) content makes up a greater proportion of content across Facebook than on “mainstream” Polish media Pages, and the fact that the engagement rates for this far-right content are also disproportionate, suggest that Polish politics on Facebook differs from Polish politics in “mainstream” Polish media in at least one way: it skews to the right. Other researchers have found evidence of a similar rightward skew on Twitter. Of course, Bosak’s increased presence in Facebook-wide content could be explained in a number of ways:

Polish users could on the whole be more conservative than the “mainstream” Pages’ content suggests, and tracking activity on Facebook merely gives us a more accurate idea of people’s actual preferences;

The audiences of far-right Pages could be more active in creating content and engaging with it than other segments of the population;

The far-right Pages could be amplifying their content more successfully than Pages in other parts of the political spectrum.

While we cannot address explanations one and two, a closer look at these Pages’ activity shows that explanation three appears to be an important contributor to the Pages’ engagement rates. Over the past two months, we have found that—while all sides of the political spectrum try to boost engagement with their messaging—the Polish far right has been particularly aggressive in its efforts to amplify its content, often using highly coordinated tactics.

How a Far-Right Network Amplifies Its Content on Facebook

One of the networks that we observed successfully spreading far-right content in a coordinated manner is a collection of Pages we call “Pantarhei” [from Heraclitus: “Everything flows”], after one of the URLs it frequently promotes. (In our next blog post, we’ll cover other, larger networks and describe in more detail how they function.)

The “Pantarhei” network consists of approximately 17 Pages, most of them created between 2015 and 2017, and with as few as 1,000 and as many as 260,000 followers. The Page names are nationalist in character: “I love Poland,” “I don’t want the Islamization of Europe,” “I choose Poland,” and so forth.

![The “Stop islamizacji Europy” [“Stop the Islamization of Europe”] Page, part of the “Pantarhei” network. The “Stop islamizacji Europy” [“Stop the Islamization of Europe”] Page, part of the “Pantarhei” network.](https://fsi-live.s3.us-west-1.amazonaws.com/s3fs-public/styles/epsa_crop/public/screen_shot_2020-03-08_at_7.55.16_pm.png?itok=SwNPjiP3)

The “Stop islamizacji Europy” [“Stop the Islamization of Europe”] Page, part of the “Pantarhei” network.

The Pages push Islamophobic, anti-US, anti-immigrant, and anti-Semitic content and boost Konfederacja politicians and causes, including Bosak’s presidential run. To this end, they also post content attacking Law and Justice and Civic Platform from the right and argue for leaving the European Union. Four content farms provide the majority of the network’s content:

Wprawo.pl: a nationalist site managed by Jacek Międlar, a former priest and far-right activist; pushes nationalist and anti-Ukrainian themes (~28.5% of urls—here and below, over the past three months)

Pantarhei24.com: appropriates and translates news from non-Polish-language websites; anti-immigrant focus (~21% of urls)

Magnapolonia.org - a right-wing news site; focus on foreign policy (especially related to the Middle East) (~15.8% of urls)

- Dzienniknarodowy.pl: a right-wing news-site related to “Roty Niepodległości” (“Legions of Independence”), a highly-organized nationalist group, and Marsz Niepodległości (“March of Independence”), the biggest annual patriotic demonstration taking place in Warsaw, accused of promoting extremist views (~9.3% of urls)

One function of these content farms is to provide Facebook-ready content which entices viewers back to the websites, where they are shown ads (and often petitioned for financial support through Paypal or other means). In this respect, networks like “Pantarhei” have a spam-like quality: they revolve around clickbait. Since the quality of the individual pieces of content themselves is not as important as their political slant or the overall commercial outcome, the Posts do not typically perform very well: the average interaction rate for outbound links (the type of Post that makes money for the operators) in the “Pantarhei” network from December 2019 to March 2020 was 0.15%. But the network operators can make up for this shortcoming by cranking out content in huge quantities and by posting it simultaneously across many purportedly independent Facebook Pages:

A misleading anti-immigrant article appearing on nine “Pantarhei” Pages at exactly 11:42am on March 6, 2020. This post got 243 reactions, 47 comments, and 83 shares across all “Pantarhei” Pages.

This mass dissemination strategy allows the Page owners to compensate for the vagaries of Facebook’s algorithm, which tends to rank outbound links lower than photos or other on-platform content, and potentially to reach more followers—in this case, over 550,000, the combined followers of these 17 Pages—than any single Page in the network can reach. At the same time, the content appears organically popular, as if the Page administrators each simply happened to choose it that day, concealing the true coordinated nature of the Page from the audience. The user, seeing only one small corner of the network, has little indication that they are seeing content from a larger campaign. It is not clear whether these amplification tactics, described by Avaaz in a 2019 report on far-right networks on Facebook and covered by SIO in reports on Taiwan and a Kosovo-based network, run afoul of Facebook’s community standards on coordination and inauthentic behavior.

The “Pantarhei” network operators do not create much of the content they share. Instead, they copy and refurbish photos and articles from other news websites, and post the content as their own. The photo for the article shown above, for instance, was taken from the New York Post; a recent anti-immigration article in the network was reappropriated from kresy.pl, another right-wing news site. This content theft allows a handful of website operators to crank out a large amount of content. From March 2 to March 9, 2020, the 17 Pages in the “Pantarhei” network posted 1,800 outbound links, or over fifteen per day per Page. Of these links, 66% appeared across multiple Pages in the network.

If it is true, as the post-count data suggest, that Polish politics on Facebook skews to the right of Polish “mainstream media,” one of the reasons for this difference might be the tactics far-right networks like “Pantarhei” use to amplify their content. The frequency with which such networks post Bosak-related content—across many Pages, occasionally multiple times—could account for the discrepancy in candidate-related content we note above.

Since mere mentions don’t translate to electoral success, it is worth asking: do Bosak’s high engagement numbers on Facebook increase his chances in the real world? There are many complex factors at work, but polls suggest that Bosak—consistently polling between 3 and 5%—has not seen any significant electoral boost from his popularity on Facebook.

While a thorough analysis of the role of Facebook in the Polish election will have to wait until after the voters go to the polls, we continue to observe these amplification tactics being used to influence the Polish electorate. In our next blog post, we will examine a series of larger, more influential networks and describe in greater detail their tactics and organization.

1. “Across Facebook” refers in this case, and in the references that follow, to all of the Pages and Groups that are visible to CrowdTangle, Facebook’s social-analytics platform, which we used to analyze Facebook activity. The “mainstream media” list consists of the Facebook Pages for: 300Polityka, DoRzeczy, dziennik.pl, FAKT24.pl, Gazeta Wyborcza, Gazeta.pl, gazetaprawna.pl, Interia, Newsweek Polska, Niezalezna.pl, Onet, Polityka, polsatnews.pl, Polska Agencja Prasowa, Polskatimes.pl, PolskieRadio24.pl, Radio TOK FM, Radio ZET, RMF FM, Rzeczpospolita, se.pl, Telewizja Republika, TVN24, tvp.info, Tygodnik Sieci, Wirtualna Polska, wPolityce.pl, and WPROST.

2. It’s important to note that these figures refer only to mentions, positive or negative; a high figure for a given candidate does not mean that they are being boosted, as critical posts are counted alongside supportive commentary.