Huawei and Global Authoritarianism

Huawei and Global Authoritarianism

CDDRL Research-in-Brief [4-minute read]

Motivation & Contribution

China has become a world leader in digital repression, including social media surveillance, internet shutdowns, website-blocking, and arrests of those posting content the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) deems threatening. These technologies have been deployed not only on Chinese citizens but have also been exported around the world, to both democracies and dictatorships. Huawei, the world’s largest — and partly state-owned — telecommunications provider, is at the center of this dynamic, having been exported to over 60 countries on every continent.

Despite the visibility of Huawei technology transfers outside of China, our understanding of how exactly this affects recipient countries is still in its infancy. Some observers see Huawei as a cornerstone of the CCP’s efforts to prop up foreign dictatorships. Others see Huawei as a source of economic growth in some of the world’s most populous and least developed countries, providing cost-effective telecommunications and infrastructure development. What is needed is systematic evidence to move beyond speculation and to better understand whether and how Huawei transfers affect repression.

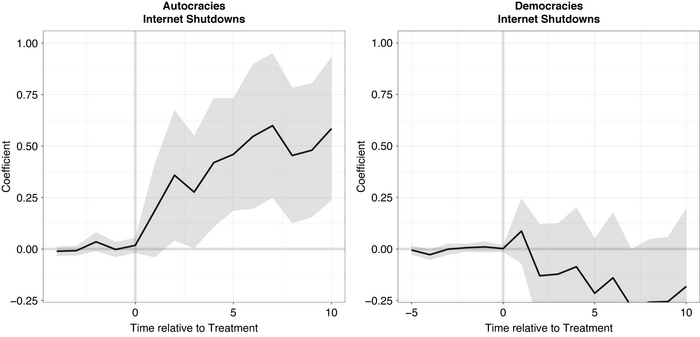

Erin B. Carter and Brett L. Carter help fill this crucial gap in our knowledge. Using data on all Huawei contracts across the world over a nearly twenty-year period, they find that Huawei transfers do, in fact, facilitate digital repression in the autocracies — but not the democracies — that receive them. Attempts at digital repression in democracies are more often checked by independent political institutions and legal frameworks. When these fail, civil society organizations, news media, and popular mobilization can step in. By contrast, autocrats tend to lack these constraints and can thus more readily use Huawei for digital repression. In short, the impact of Huawei transfers varies depending on regime type.

The article compellingly demonstrates the enduring role of political institutions — in this case, those enabling democratic resilience. In addition, it sheds light on one mechanism underlying the so-called global wave of autocratization, namely, Huawei transfers that enable dictators to more efficiently control their citizens. And from a methodological standpoint, the paper provides the “first cross-country, plausibly causal evidence” of the effects of Huawei on repression.

Data & Methods

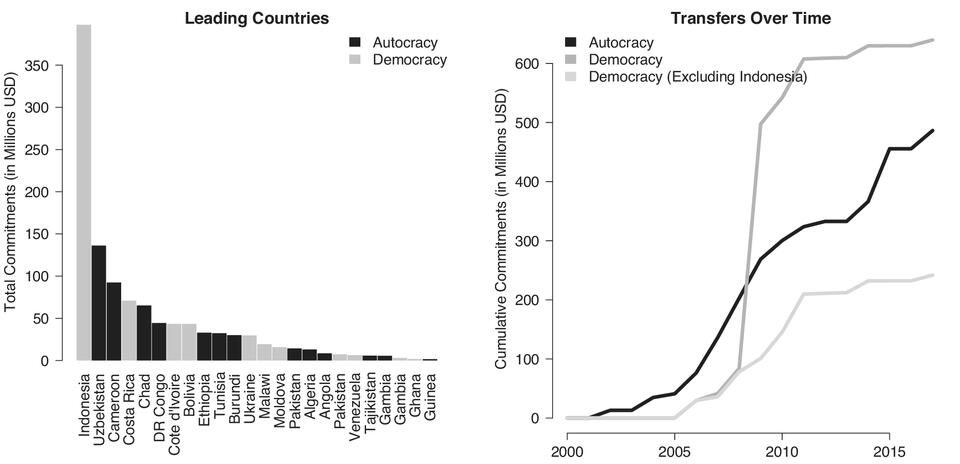

The authors use data on Huawei contracts from 2000 to 2017, which comes from the AidData project. This includes 153 projects — almost entirely on communications technologies — in 64 countries worth over $1.5 billion. The vast majority of recipient countries are in Sub-Saharan Africa and Central, South, and Southeast Asia. Huawei is responsible for around 70% of all telecommunications in Africa alone. The single largest recipient of Huawei transfers is Indonesia (~$391 million of contracts), followed by Uzbekistan (~$150 million) and Cameroon (~$100 million). Notably, of the top 20 recipient countries, only one (Costa Rica) is considered “Free” by Freedom House, the rest being “Partly Free” or “Not Free.” Huawei transfers flow slightly more to democracies than to autocracies, but this is only if Indonesia is included; otherwise, transfers flow disproportionately to autocracies.

Carter and Carter quantify the effect of Huawei transfers on repression by using the generalized synthetic control (GSC) method. The goal is to compare those countries receiving (the “treatment”) of Huawei transfers with those in the “control group” that do not. However, comparing the treated and controlled countries or “units” is difficult for several reasons. For one, the countries that receive Huawei transfers differ from those that do not, for example, in terms of their political institutions and economic development. In addition, there is a lag of several years between receipt of Huawei and its full implementation, and the effects of Huawei transfers may take several years before they are fully realized. Similarly, transfers are staggered over time; for example, the largest number of contracts was signed as China’s Belt and Road Initiative expanded between 2014 and 2015.

Comparing (such ostensibly different) treated and controlled units can be facilitated by constructing a “synthetic” control out of multiple control units. This will more closely match the treated unit’s characteristics prior to receiving Huawei. GSC extends (or generalizes) the synthetic control method by enabling comparison across multiple time periods (given the staggered rollout mentioned above), and across countries with different backgrounds prior to adopting Huawei technologies. Separate tests are then run for autocracies and democracies to capture how political institutions influence the effects of Huawei transfers.

Findings

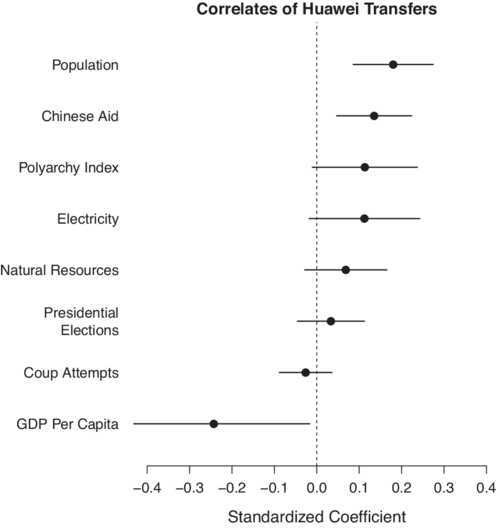

In addition to the central finding about regime type, the authors also provide evidence that the countries most likely to contract with Huawei are more populous and poorer. These countries are, from China’s standpoint, attractive markets, and their governments appreciate the subsidies offered by China’s Export-Import Bank. As such, transfers are driven, in part, by demand in recipient countries. In addition, recipient countries are also more likely to have received Chinese aid and, therefore, recognize the One China policy. Meanwhile, autocracies, coup-prone countries, and those rich in natural resources are not more likely to receive Huawei transfers. All of these findings should be qualified by the secrecy surrounding Huawei contracts. Indeed, many such contracts include confidentiality clauses that prohibit recipient countries from divulging information.

Correlates of Huawei technology transfers

Another set of findings relates to those democracies that do use Huawei to digitally repress, even if transfers do not systematically increase repression in democracies. India is an important case, as it is a world leader in periodically shutting down the internet. Unsurprisingly, democracies whose political institutions and civil society organizations have been weakened by elected leaders with authoritarian ambitions (such as Narendra Modi) seem more likely to impose shutdowns or monitor media. At the same time, weak democracies are unlikely to use Huawei to block websites or arrest their citizens for digital action. As Carter and Carter point out, this highlights the importance of disaggregating the concept of digital repression as well as the set of institutions that enable democratic resilience. Ultimately, “Exporting the Tools of Dictatorship” is exemplary in its use of systematic data to shed light on a complex and contested geopolitical issue.

*Research-in-Brief prepared by Adam Fefer.