Democracy, Autocracy, and Performance Legitimacy

Democracy, Autocracy, and Performance Legitimacy

CDDRL Research-in-Brief [4-minute read]

Motivation & Contribution

Over the past 10-15 years, both longstanding and relatively new democracies have suffered from backsliding and erosion, including India, the United States, Brazil, Turkey, and many others. Many social scientists have explained this wave of backsliding in terms of either (a) elected autocrats who undermine democracy from within or (b) declining popular support for democrats who have failed to deliver economic growth and prosperity. However, recent scholarship by Thomas Carothers and Brendan Hartnett has questioned the wisdom of the latter. For example, India enjoyed strong economic growth prior to its backsliding under Narendra Modi.

In “Delivering for Democracy,” Francis Fukuyama, Chris Dann, and Beatriz Magaloni set out to more systematically evaluate the evidence connecting popular support for democracy with delivery, examining both backsliding and non-backsliding countries. After finding preliminary evidence for the democracy-delivery relationship, they offer an explanation of why delivery is simultaneously so important and so elusive under democratic governance.

Evidence

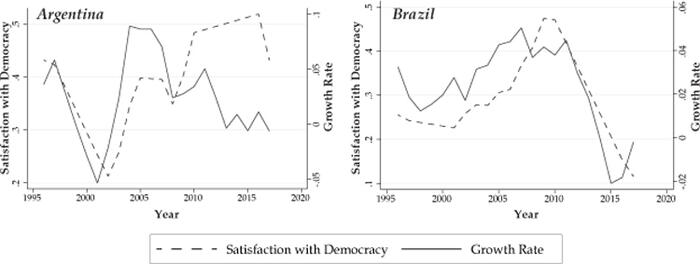

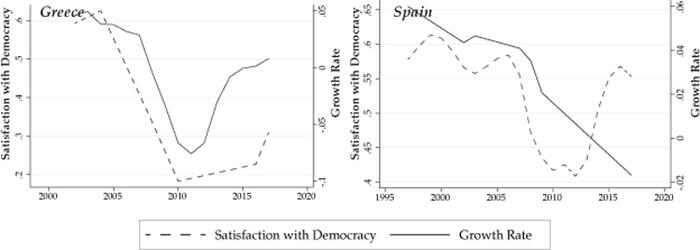

Using ten data sources covering 650,000 people in both old and new democracies, the authors find a strong, positive correlation between satisfaction with democracy and economic performance. This relationship holds not only for many countries at one point in time but for pairs of countries over time. In two developing democracies — Argentina and Brazil — as well as in two developed democracies — Greece and Spain — satisfaction and delivery have been closely connected since 2005, plummeting during economic crises and rising during periods of prosperity. These patterns call for an explanation for why voters care so much about delivery, such that they may be willing to sacrifice their democratic freedoms for it.

The Argument

Delivery is Important

The authors begin from the axiom that stable political life depends upon citizens perceiving their governments as legitimate. Legitimacy can be thought of in terms of both performance — the effective delivery of goods and services — and procedure, which encompasses policies that reflect the democratic will of the people. As the examples of China, Turkey, Saudi Arabia, and Singapore show, however, plenty of autocracies and backsliding democracies have not only delivered, but have also arguably outperformed their democratic peers. From China’s Belt and Road Initiative to Turkey’s Yavuz Sultan Selim Bridge, authoritarian leaders and ruling parties have achieved remarkable performance legitimacy.

Although autocracies, by definition, cannot be procedurally legitimate, this may carry little weight for democratic citizens who experience prolonged unemployment or must deal with dilapidated infrastructure. Indeed, public engagement through procedural channels — such as voting or jury service — has steadily declined across the democratic world. Democratic voters are increasingly willing to support outsider candidates who build new infrastructure or promise to fight crime, but who nonetheless restrict their political freedoms. Many citizens of El Salvador — which now claims the world’s highest incarceration rate — continue to view Nayib Bukele’s administration as the surest way of delivering security, despite a years-long state of emergency that has seriously eroded democratic freedoms.

Meanwhile, established democracies built much of their infrastructure decades ago, so investments primarily maintain these systems, rather than showcasing new projects that can garner public support. In some cases, democracies have struggled to even maintain their existing infrastructure, perhaps best exemplified by the collapse of Baltimore’s Francis Scott Key Bridge. All of this creates the conditions for voters to support far-right, anti-democratic parties, which often blame immigrants for economic problems and propose illiberal solutions.

Yet Democratic Delivery is Difficult

Elected democrats seeking to deliver may find themselves hamstrung in ways that autocrats are not. For one, democratic institutions are composed of ‘veto players’ who can stymie the introduction of badly needed policies: national and subnational governments, multiple legislative chambers, judges who review and overturn executive action, and so on. At the same time, democrats must worry about election cycles and term limits, decreasing their incentives to deliver for the long term when later politicians may take credit. Meanwhile, legal and regulatory systems, such as those intended to protect the environment, may prevent the building of critical infrastructure. Property rights prevent the forcible displacement of communities for development, while civil liberties prevent the repression of those who refuse to be displaced. Rules meant to prevent regulatory capture often become arenas where powerful interest groups block and delay government action.

Independent news media present another potential impediment to delivery, as criticism from journalists can make incumbents wary of undertaking new projects. In addition, media bias can convince voters to remove politicians who do, in fact, deliver. By contrast, autocrats who censor media and arrest journalists can focus on delivery alone, even while their development schemes often rest on corrupt and nepotistic practices. Popular discontent with democratic government ultimately creates a damaging feedback loop: voters are unwilling to fund government projects, in turn leading government to function worse, generating further discontent.

Prospects

Autocrats have figured out ways to deliver the goods and services their citizens want, but this does not make autocracy a just political system. By the same token, democracies may struggle to deliver, but their procedural legitimacy — especially voters’ ability to hold representatives to account — entails a powerful means of generating fair and inclusive delivery. As such, the authors call on democracies to examine their past and that of their peer countries — both developed and developing — for inspiration. For example, the U.S. New Deal was exemplary in building ambitious and popular infrastructure, as well as providing broad social and economic protections. (Of course, most of these projects would be hamstrung by modern-day regulatory frameworks.)

Meanwhile, Australia’s citizens have both benefited from a recent infrastructure boom and have demonstrated strong support for democracy. Finally, many Latin American countries have implemented popular and effective programs like conditional cash transfers. For the authors, addressing the issues most pressing to voters — such as job creation, which is especially salient to young people, who are most dissatisfied with democracy — will require democratic governments to strike the right balance between democracy and delivery.

*Research-in-Brief prepared by Adam Fefer.