In Sierra Leone, Stanford researchers empower rural poor

In Sierra Leone, Stanford researchers empower rural poor

Baomahun, Sierra Leone – Mud huts dot the dusty landscape in this remote part of Sierra Leone. The only visible sign of technology is a community well pumped by young women, some with babies strapped on their backs.

The roads leading to Baomahun are gutted and torn, crossing over vast mineral deposits that helped fuel a decade-long civil war. Sierra Leone is rich in resources, but cursed with corruption and greed that stalls its progress.

A team of Stanford researchers pull up to the village in four-wheel drive vehicles, stiff and sweaty after the long trip from the capital city of Freetown. They are welcomed by a group of laughing children who closely inspect the foreign visitors, a rare site in a village that is largely untouched by the modern world.

Led by Jeremy M. Weinstein, an associate professor of political science and senior fellow at the Freeman Spogli Institute for International Studies, the graduate students are working with Timap for Justice, an organization based in Sierra Leone that uses community-based paralegals to serve the interests of the rural poor. During the week-long trip, Timap's paralegals are taking the Stanford team to villages like Baomahun to get a first-hand account of how natural resource concessions impact poor communities.

The students are part of Rebooting Government – a new course Weinstein teaches at Stanford's Hasso Plattner Institute of Design to come up with new approaches to solving complex governance challenges around the world.

“There is a huge opportunity to leverage the ingenuity and diverse skill-set of Stanford students to support the work of local innovators who are tackling really difficult governance problems in their own environments,” said Weinstein who also leads the Center for African Studies at Stanford. “And the tools of human-centered design help our students and partners think about these problems in a fundamentally different way.”

The resource curse

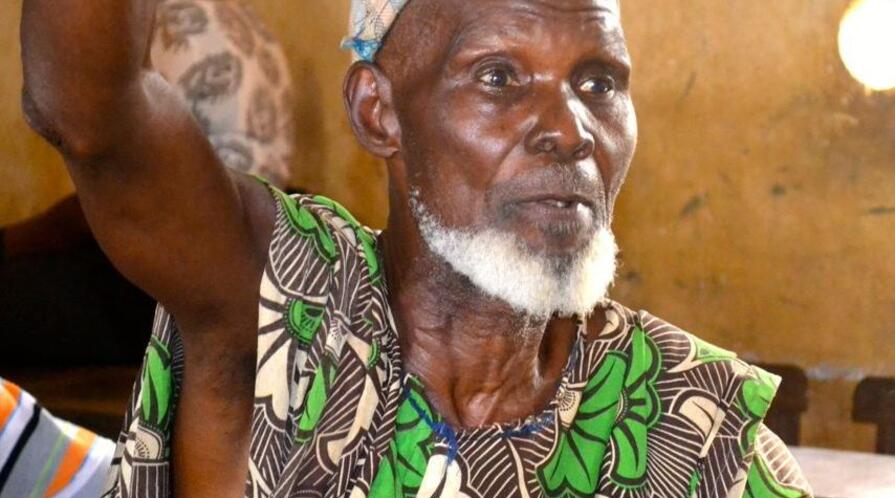

Timap's lead paralegal, Abdulai Tommy, introduces the Stanford team to a group of village leaders, landowners and miners assembled in an outdoor community center. The team is late and their audience is visibly impatient. But they are eager to tell their stories – to be heard.

The town chief points a calloused hand towards a modern building perched on a hill above the village.

"The mining compound shines in brightness 24/7 while we live here in darkness," he said. "How is it that the land belongs to us and they enjoy themselves while we do not enjoy anything?"

Ramya Parthasarathy, a Ph.D. student in political science, scribbles notes while an unemployed miner describes the poor working conditions and low wages he was paid - as little as 2 USD per day - for back-breaking labor. Looking at the ground, he confesses that he can hardly support his family after being sacked from his job months ago.

The student team is here to collect the information they need to design new tools and approaches for Timap's work empowering rural communities who confront the powerful interests of foreign mining and agricultural companies. The race by foreign

|

|

A young girl drinking water from a well in Baomahun village. Photo Credit: The Author |

companies for natural resource wealth in the developing world continues to foster corruption and undermine rural livelihoods, and the Stanford course is envisioning new approaches to address these challenges.

An advertisement posted in the community center warns against the dangers of illegal mining. It is sponsored by Amara Mining, the U.K.-owned company that has been mining gold in Baomahun for 10 years.

The town chief mentions a cholera outbreak that killed 15 people a few months ago. He blames Amara Mining for contaminating the ground water.

As the afternoon sun beats down on the parched land, a young girl quenches her thirst with water drawn from the town well.

Disrupting the system

Amara Mining is just one of a handful of small-scale mining companies in Sierra Leone that Stanford research shows buy mineral rights for cheap and give little in return. Concession agreements are often signed by government officials in Freetown, and village landowners are forced to accept the terms and conditions.

Little - if any - of the resource wealth or social services promised in these agreements trickle down to villages like Baomahun where 80 percent of the population cannot read the contracts written in English.

Computer science student Kevin Ho and his team envision using mobile phones to connect landowners who are separated by distance and poor infrastructure. They can share information on mining contracts and negotiations through SMS messages and voice activated alerts can be triggered for those who cannot read.

Organizing landowners associations to increase communication and mobilization can give them the bargaining power they need to pressure mining companies like Amara for more.

A innovator in justice reform

In a country of six million, there are just a dozen resident attorneys to serve Sierra Leone's rural population.

In 2003, Simeon Koroma left a comfortable job in private practice to start Timap for Justice, which translates to "Stand-Up for Justice" in the local Krio language. He was inspired to find an alternative to the formal legal system, which is so overburdened that some detainees wait several years for a judge to hear their case.

|

|

Simeon Koroma (right) talks with his chief paralegal in Yele village. Photo Credit: Michael Lindenberger |

With the majority of citizens seeking justice through informal or customary channels, Koroma created a network of paralegals to provide mediation and advisory services.

Koroma spent the spring in residency with the Program on Social Entrepreneurship at FSI's Center on Democracy, Development, and the Rule of Law. The program is designed for grassroots leaders who want to re-engage in academia to enrich their work and deepen their impact. It also provides students the opportunity to connect with practitioners inside the classroom to work on concrete projects with partners like Timap.

Koroma was a natural partner to Weinstein when he was developing the new course as Timap works in rural areas like Baomahun that are hurt by resource concessions.

"This experience has generated new solutions that Timap has not thought about before, and helped to refine some of our strategies and approaches to supporting communities most affected by mining concessions," said Koroma, who returned to Sierra Leone in June to begin implementing some of the ideas.

Listen first - design later

The following day, Jonny Dorsey - an MBA student at Stanford's Graduate School of Business - meets with the bauxite mining company Vimetco where a worker strike has halted operations for nearly a week. Dorsey learns the company is operating at a significant loss for the year. The general manager expresses a deep distrust towards the miners who he accuses of theft and trying to make "a quick buck."

Ibrahim Dowa cleans bauxite waste for Vimetco. He talks about the low pay, unsafe conditions and casual employment policies at the mine. He has joined the worker strike and threatens to block the roads if he doesn't receive more money and a stable work contract.

Listening to the needs and experiences of both stakeholders leads the Stanford team to propose creating company liaisons - drawn from the community - to mediate conflicts and ease tensions between the companies and workers.

"Immersing ourselves in the lives, hopes and desires of the individuals we met in several villages gave us unexpected insights that we would never have guessed sitting at Stanford," said Aaswath Raman, a Ph.D. student in applied physics. "Our empathy building work revealed a reservoir of latent power and resolve among village residents that formed the foundation of our idea of community liaisons."

Sparking new ideas

Michael Lindenberger, a journalist and Knight Journalism Fellow at Stanford's School of Communication, strolls through Yoni village where Agri Capital is operating a farm cultivating Vietnamese rice. Children with distended bellies kick around a deflated soccer ball clouding the air with red dust.

The town chief presents the Agri Capital contract to a Timap paralegal explaining how the company receives just one bushel of rice in return for each acre the company farms. The chief, whose tattered clothes drape over his frail body, describes how the village was not consulted on the terms of the contract. The little rice they have received is dirty.

"Not fit to eat,” he says.

Koroma shakes his head as he scans the 14-page contract. The signatures of the landowners are absent from the contract that negotiated 3,000 acres of their land for filthy rice.

The chief turns to Koroma and with a deflated expression cries. "We are suffering, he says. "Just looking to survive."

|

|

Professor Jeremy Weinstein (left) shakes hands with the Paramount Chief in Bumpe chiefdom. Photo Credit: Michael Lindenberger |

Koroma is hopeful that organizing landowners into local associations may give them the power to demand more.

While there is no silver bullet to solve the range of issues facing rural communities in Sierra Leone, it is Weinstein's hope that the course will spark new ideas to long-standing problems.

"If we can get students excited about the possibility of making governments work better for people – and do some good through our class-based projects – we’ll be able to focus Stanford’s innovation energy on some of the world’s most important problems," he says.