Gellman talks about Snowden revelations

Journalist Barton Gellman had left his job at The Washington Post and was working on a book about surveillance and privacy in America when he was contacted last year by someone using the code-name VERAX, or “truth teller” in Latin.

So began one of the most dramatic chapters in the history of modern American journalism – and government surveillance. In the spring of 2013, Gellman began having remote, encrypted exchanges with someone who clearly had inside knowledge of the NSA's global and domestic surveillance programs.

“He was trying to figure out whether he could trust me and ... I was trying to figure out if he was for real,” Gellman told a packed Stanford audience Monday night.

Last December, he traveled to Moscow to put a face to the code-name and determine whether the information he was providing was accurate.

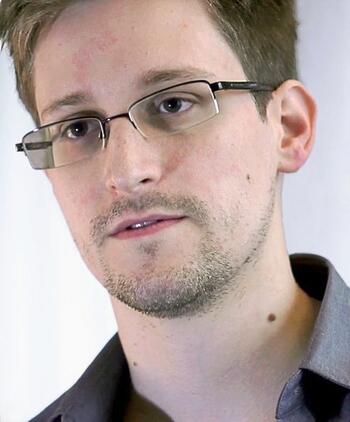

“All extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence – and he was providing that.," Gellman said of former NSA contractor Edward Snowden. "I was convinced fairly early on that I was dealing with something fairly serious.”

So Gellman went back to The Washington Post, where he had been on teams that won two Pulitzer Prizes for their coverage of the 9/11 terrorist attacks and the power and influence of Vice President Dick Cheney during the Bush administration.

“I went there because I trusted them and because I wanted their resources and their advice,” he told the audience of some 600 people at the CEMEX Auditorium on Monday. The Washington Post would go on to win the 2014 Pulitzer Prize for Public Service, shared with The Guardian US, for their reporting on the Snowden materials and the NSA.

Gellman today is a senior fellow at The Century Foundation and a visiting professional specialist and author-in-residence at Princeton’s Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs. He is the author of Angler: The Cheney Vice Presidency and is currently working on a book about the Snowden affair.

Snowden’s explosive disclosures about the National Security Agency’s intelligence-collection operations have ignited an intense debate about the appropriate balance between security and liberty in America.

In a special series this academic year at Stanford University, nationally prominent experts are exploring the critical issues raised by the NSA’s activities, including their impact on our security, privacy and civil liberties.

Amy Zegart, co-director of CISAC and a senior fellow at the Hoover Institution, launched the “Security Conundrum” series in October with its first speaker, Gen. Michael Hayden, the former director of the NSA and CIA who defended the government surveillance programs. The metadata collection “is something we would have never done on Sept. 9 or Sept. 10,” Hayden told Zegart during their conversation on Oct. 8. “But it seemed reasonable after Sept. 11. No one is doing this out of prurient interests. No – it was a logical response to the needs of the moment.”

Zegart, in introducing Gellman, said: “Tonight, we move from inside the NSA to inside the newsroom, which played a key role in revealing the NSA’s secret activities over the past year.”

All Photos by Rod Searcey

In the second lecture in the “Security Conundrum” series, Gellman was in conversation with Philip Taubman, former correspondent and Washington and Moscow bureau chief for The New York Times and a consulting professor with Stanford’s Center for International Security and Cooperation (CISAC). Taubman teaches the class Need to Know: The Tension Between a Free Press and National Security Decision Making.

Gellman recounted his dealings with Snowden and described how he and his editors weighed the Snowden materials. Few questions are more difficult for American journalists than determining how far a free press can venture in disclosing national security secrets without imperiling the nation’s security.

“I asked him very bluntly, `Why are you doing this?’” Gellman said of Snowden.

“He gave me very persuasive and consistent answers about his motives. Whatever you think of what he did or whether or not I should have published these stories, I would claim to you that all the evidence supports his claim that he had come across a dangerous accumulation of state power that we, the people, needed to know about.”

One of the first Snowden revelations, Gellman said, was the top-secret PRISM surveillance program, in which the NSA is allowed to tap into the servers of nine large U.S. Internet companies, including Google, Microsoft, Yahoo, Facebook and Skype. Snowden believed the extent of mass data collection about American citizens was far greater than what the public knew.

The Post reported that PRISM allows the U.S. intelligence community to gain access from the Silicon Valley firms to a wide range of digital information, including audio, video chats, photographs, emails and stored data that enable analysts to track foreign targets. The program does not require individual warrants, but instead operates under the broader authorization of the federal Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act court.

The FISA Court had also been ordering a subsidiary of Verizon Communications to turn over to the NSA logs tracking all of its customers’ telephone calls.

Gellman said Snowden asked for a guarantee the Post would publish the full text of a PowerPoint presentation that he had obtained describing the PRISM program. Gellman told him that his editors would not make any guarantees about what they would publish and in the end the paper only reproduced several slides so as not to harm national security.

Taubman asked Gellman what gives any journalist the right to publish classified documents and not hand those papers back to the NSA.

“I’m not accountable to anyone for my decisions about what is in the interest or not in the interest of the national security of the United States,” Gellman said. “What happens is the government tries to keep information a secret and I try to find it out – and then when that spillage happens, well, then we talk.”

In the case of PRISM, he sent emails to two “quite senior people” in the government and told them this was the type of email he only sends once every several years, when he is onto a big story they would want to know about. But he didn’t want to do anything over email, so when the senior officials called, Gellman gave them the title of the document about which he was going to write.

That started the negotiations with the government and The Washington Post. In the end, the paper only published several of the government’s PowerPoint slides that explained the PRISM program because they were concerned about harming national security.

“We had no interest in doing that; we only had an interest in writing about the public policy question on a program that had secretly expanded in ways that almost no one knew about,” Gellman said. “To the extent that it involves drawing new boundaries allowing the government to spy on its citizens and the citizens never get to know that – that is quite relevant to know when you’re trying to decide whether you like what your government is doing.”

In a statement responding to the PRISM revelations by the Post, Director of National Intelligence James Clapper said information collection under the program “is among the most important and valuable foreign intelligence information we collect, and is used to protect our nation from a wide variety of threats.”

Clapper called the Snowden leaks about the legal program “reprehensible and risks important protections for the security of Americans.”

Gellman said Snowden has turned down million-dollar book and movie deals and lives in “ascetic” asylum in Russia. Snowden told NBC News earlier this year that he was on his way from Hong Kong to Latin America, via Moscow, when his passport was confiscated and that Russia then granted him a one-year asylum.

“He is fascinating to me because he’s an unusual figure,” Gellman told Taubman, who had asked him what Snowden was like. He said the 31-year-old former systems administrator for the CIA did something most Americans would not: He gave up his personal freedom and changed the course of his life to make public the government surveillance programs that he believes are a danger to the American people.

“He described himself to me once as an indoor cat,” Gellman said. “He lives in a virtual world; there’s not a whole lot of difference for Snowden whether he’s living in Moscow or Hawaii – he’s is what I would call a net native. He has an ascetic personality; he doesn’t have or want very much stuff.”

Gellman added: “He is sort of Zen-like in his confidence that he has done the right thing.”

***

The Security Conundrum series is co-sponsored by CISAC, Hoover, and the Freeman Spogli Institute for International Studies, Stanford Continuing Studies, Stanford in Government and the Stanford Law School.

Other nationally prominent speakers will include Reggie Walton, the former presiding judge of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court, and U.S. Sen. Dianne Feinstein, chairman of the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence.