REAP in Caixin Report: Anemic Babies

Why are rural children falling behind even before they enter school?

Why are rural children falling behind even before they enter school? Read more to learn about efforts to tackle China's "nutritional poverty" problem.

To read the article in Chinese, click here.

Caixin Report: Anemic Babies

| Image

|

|

The Rural Education Action Program (REAP), co-directed by Stanford University’s developmental economics Professor Scott Rozelle, has sent a team of volunteers to traverse the Shaanxi countryside giving babies health checkups. Photo provided by REAP |

When Liu Lei and Yu Gui look out from their house at the foot of the mountains, they see a village surrounded on all sides by an endless expanse of mountains. They live in Shuang Jian Village in the southern part of Shaanxi Province (Ningshan County, Ankang Prefecture) and have a son who recently celebrated his first birthday. However, there is one thing that these 21 year-old new parents don’t know—their baby is already severely anemic.

Just like most of the other young people in their village, after graduating from high school Liu Lei and Yu Gui went to the big cities of southern China to find work. After their son was born, they returned home in order to take care of him. The Rural Education Action Program (REAP), co-directed by Stanford University’s developmental economics Professor Scott Rozelle, has sent a team of volunteers to traverse the Shaanxi countryside giving babies health checkups. The Qingba mountain region in southern Shaanxi, the Baiyu mountain region in northern Shaanxi, and the Tushi mountain region along the shore of the Yellow River are some of the most concentrated impoverished areas in the country. According to REAP’s surveys, many of these children have hemoglobin levels of only 87 g/L (the standard for healthy babies is 110 g/L).

Many surveys have shown that, in part because of poverty but primarily because of insufficient awareness and understanding, the nutritional status of infants in China’s poor rural areas is very concerning. Poor nutrition at this early stage of life irreversibly impacts physical and cognitive development. This means that this generation of children, on whom the two previous generations have placed their hopes for happy lives, may be falling behind before they even reach the starting gate.

According to the “China Development Report on Nutrition Among Children Aged 0-6 Years,” issued in 2012 by the former Ministry of Health, in 2010 the national prevalence of anemia among 6-12 month-old children was 28.2%. Among 13-24 month-old children, the rate of anemia was 20.5%. In poor rural areas, the situation was even more dire. In April of this year, REAP conducted health checkups for 1,000 6-12 month-old babies in 11 poor counties in Shaanxi Province. That survey found that the rate of critical anemia within that population was 55.7%. Including borderline cases of anemia, the rate was a full 80%. Another study undertaken by the China Development Research Foundation (CDRF) in Qinghai Province in 2009 and in Yunnan Province in 2010 found that in both places the average anemia rate of 6-24 month-old infants was over 60%. In Yunnan, 36% of tested infants between 12-23 months of age were also found to be stunted (low height for their age, an indicator of macronutrient deficiency).

In the past few years, under pressure from non-governmental forces, rural children’s health has garnered more and more official attention. In 2011, China officially launched the “National Rural Compulsory Education Student Nutritional Improvement Plan.” This plan calls for the investment of tens of billions of RMB every year to provide free nutritional meals to school-aged children. In spite of this great step forward, many institutions and public figures are now suggesting that even more needs to be done. In particular, many have pointed to the importance of interventions that target children in the most critical window of their development—the period before they reach two years of age.

Caixin reporters have recently been informed that a more ambitious and overarching program referred to as the “National Outline for the Development of Children in Poor Areas” has already been signed by 9 national bureaus and is awaiting consideration by the State Council. The plan will focus its efforts on over 40 million children between 0 and 15 years of age across 680 nationally designated poor counties. The proposed plan will provide nutritional supplement packages to 0-36 month-old children throughout these areas. These nutrition packages do provide some calories, but the key is to provide the vitamins and minerals that are essential to infant growth. In the majority of Chinese rural households today, these micronutrient needs are overlooked. Based on international and domestic research experience, if it can be successfully implemented this plan has the potential to enormously improve the state of infant nutrition across China’s poor rural areas.

Falling Behind at the Starting Line

It is well known that rural children’s poor nutrition starts long before they enter school.

“Some people are born into inequality,” says Lu Mai, the secretary-general of the China Development Research Foundation (CDRF), an influential organization that has been conducting research in China’s rural areas for many years. REAP’s Scott Rozelle has felt a deep connection to rural China ever since he first came to the PRC in the 1980s. Long hoping to break the chain of the intergenerational transmission of poverty, Rozelle finally concluded that the solution must be found not in the realm of agriculture but rather of education. And the most important task of all is making sure that children are getting proper nutrition. Starting around 2006, both Lu Mai’s CDRF and Rozelle’s REAP teams switched their focus almost simultaneously onto the intertwined issues of child nutrition and education. Along with several other organizations, these two groups began working to promote the launching of the National Rural Compulsory Education Student Nutritional Improvement Plan. Both groups also firmly believe that interventions targeting school-aged children’s nutrition are insufficient—such interventions come “too late” for China’s rural children.

Only after driving east from the Ningshan County seat for an hour and a half along a twisting mountain road, reaching 1,563 meters above sea level along a narrow gully do you reach Tai Shan Miao Township’s Shuang Jian Village. Ningshan County is located in the Qingling Mountains—the famous dividing line between northern and southern China. The forest coverage within this steep, mountainous region is around 90.2%. The villagers live scattered across whatever narrow patches of flat land can be found. There are even some families living alone on the tops of mountains. In 2011, the average per capita net income among the county’s farmers was 4,815 RMB. The county’s total fiscal revenue was about 65 million RMB. It is a nationally designated poverty county.

Liu Lei, Yu Gui and their child’s two grandparents all live together in a traditional two-level, black tile house. With her hair tied back in a ponytail, Yu Gui holds her child. Yu Gui still has the delicate features of a young woman. Her husband Liu Lei also looks little more than a boy. They intend to stay at home with their child until he is about 16 months old. Then they will leave the child with their parents and migrate together to a city to find work. This remains the only viable choice for many young rural parents.

This family has one other member, Liu Lei’s 72-year-old grandfather. Small of stature with stooped shoulders, he spends his time silently examining the recent addition to the family or quietly going about his work without asking questions. The family refers to him as a laoshiren—“a naïve person” with poor mental development. Among the over 200 residents of this village, there are probably 10-15 laoshiren of his generation. Their situation is very likely related to poor nutrition. In another village in Ningshan, in the home of the village party secretary, you can find another laoshiren. He is the party secretary’s younger brother and has the same blank expression and the same quiet way of sitting on his stool husking corn. These laoshiren are both lifelong bachelors.

Rural living conditions are much better today than they were for the previous generation. Seven or eight years ago, Liu Lei’s parents began cultivating mushrooms in the county, earning them an annual net income of about 30,000 RMB. Many similar middle-aged villagers have had to leave their hometowns just like the young people to find migrant work. They go to tiring jobs in the mines in the mid-west or to construction sites and factories in the big cities. At these jobs the lowest salaries are 2000-3000 RMB per month and the highest are over 10,000 RMB. But even with their rising incomes there has been no obvious improvement in the state of child nutrition in these areas.

“After we fed the baby his digestion was bad. We didn’t dare give him rice, meat or other solid foods again.” So spoke Yu Gui and her mother-in-law during an inquiry into caregivers’ nutritional knowledge conducted by REAP volunteers. The baby’s caregivers think a diet of formula, rice porridge and noodles will provide the best nutrition for their child. Yesterday, all the baby had to eat was about 600 mL of formula plus some left over fried rice from the adults’ meal including small pieces of green beans and pumpkin. They’ve never taken the baby to get a health checkup. The baby’s grandmother asked the volunteers why the skin on the child’s fingers was always peeling. This is actually a known indicator of vitamin deficiency. Sure enough, the volunteers’ health test showed that the baby was severely anemic.

The results from REAP’s surveys in 11 counties in Shaanxi Province and the CDRF’s work in Guizhou and Yunnan Provinces all demonstrate that for many of the rural children in these areas malnutrition begins during the period of infancy.

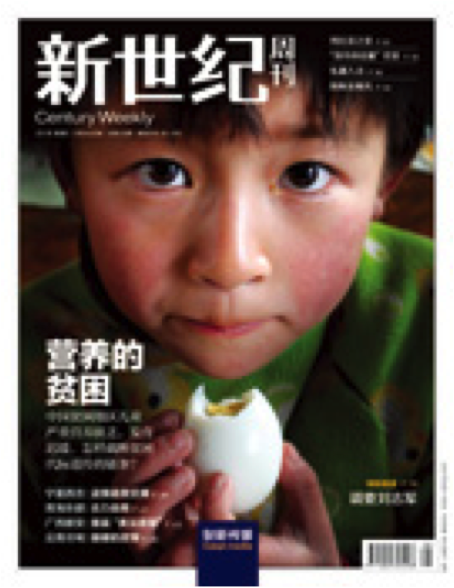

| Image

|

| A cover story in this publication from 2011 “Nutritional Poverty,” focusing on nutritional deficiencies among school-aged children in poor rural China. |

Outmoded Dietary Customs

Both REAP and the CDRF have found in the course of their research that poverty is not the main reason for the high prevalence of undernutrition across these areas. Rather, babies are being left undernourished primarily due to caregivers’ poor understanding of proper health and nutrition as well as their commitment to outmoded dietary practices. “Some parents sell all their chicken eggs to buy chicken feet,” Lu Mai says. “In analyzing the data we have discovered that less than 30% of parents believe that babies need vitamins and minerals for healthy growth,” says Renfu Luo, the REAP program director from the Chinese Academy of Science’s Agricultural Policy Research Center.

The condition of children that have been “left behind” by migrant parents is likely even worse. [In rural China, more and more parents must leave their rural hometowns to travel to big cities to find work. In general, their young children are then left to be raised by their grandparents.] REAP’s research has shown that child’s anemia status is negatively correlated with mother’s level of education. Because most children’s grandparents either only finished elementary school or never attended school at all, their ability to absorb new information and reject traditional attitudes is even less than babies’ parents. The All China Women’s Foundation has calculated based on 2010 Census data that there are about 23 million rural children between 0 and 5 years of age that have been “left behind” by at least one migrating parent. Of those, about half have been left behind by both parents, mostly to be raised by uneducated or nearly uneducated grandparents. “A lot of what they ask I don’t understand,” one child’s grandmother told a Caixin reporter.

While lack of knowledge is a major problem, there are also some families that are still greatly affected by poor economic conditions. In Simudi township, about 50 kilometers west of the Ningshan county seat, 34 year-old Zheng Changhui took her baby with her to rent a small one-story house in the township center. They originally lived with the rest of their family in Taishanba village on the top of the mountains, about a 7-hour round-trip voyage from the township center. Back then they would generally only come down the mountain into town once every two weeks. “When my daughter was young her nutrition was bad. Now she has a very weak immune system. When we went to the hospital for a health checkup they said she was deficient in just about everything. But back then our living conditions were bad. The medicine the doctor prescribed cost 200 RMB for one box. After taking one or two boxes we had to stop.” Her daughter is now four years old. She often cannot go to preschool. “I don’t want my daughter to feel inferior. I want to let her participate in lots of activities. But she is just not strong enough,” Zheng Changhui says.

Liu Lei and Zheng Changhui both hope their children will be able to get a good education. This is the wish of many parents and officials in Ningshan County. It is often the case that the more “backward” a place is, the more they see the value of education. Indeed, in 2011 this poor county began providing a full 15 years of free education: from pre-school all the way through the end of high school.

However, international health and nutrition experts have established that the first 1000 days of life, from conception until two years of age, is a critical window in which maternal and infant nutrition has an impact on lifelong health. If a child is malnourished during this period, the long- and short-term damage is irreversible and irreparable. The short-term damage is manifested in sluggish physical and cognitive development as well as an increase in morbidity and mortality. The long-term damage takes the form of delayed cognitive development, decreased ability to learn and work, and increased risk of cardiovascular disease, diabetes, hypertension, and other chronic conditions.

The Repercussions of China’s Family Planning Policy

Helping children’s guardians obtain necessary infant care and health care information was once a service provided by government public health organizations. Today, rural parents have no knowledge of these issues.

Government functions related to maternal and infant nutrition and health were long concentrated in the former Ministry of Health and the former State Family Planning Commission. These institutions’ members extended to the village level. Back then, the Ministry of Health bore responsibility for monitoring maternal and child health indicators, giving maternal and child health care guidance, and providing free infant immunizations and health checkups. The State Family Planning Commission, from the perspective of raising the quality of the population, took responsibility for interventions to stem birth defects and monitor children’s early stage development. As a result of reform policies enacted in 2013, these two governing bodies were brought together to form a single body: the National Health and Family Planning Commission.

The former Ministry of Health has released a number of guidelines, including “Chinese Infant Feeding Tactics,” “How to Regulate Sales of Breast Milk Substitute Products,” and “Infant Feeding and Nutrition Technical Guide.” The Ministry has required various grassroots organizations to help disseminate this information and has acted as a guiding presence for all work related to children’s nutrition. Since the launching of intensified medical and health reform efforts in 2009, national basic public health service programs have begun to incorporate maternal and infant health care content. They have also begun to provide urban and rural residents with free maternal nutritional guidance and health examinations for children under 3 years of age. They also provide childhood development and psychological behavioral assessments, guidance on proper practices for breast feeding, adding supplementary solid foods, and preparing meals. Finally, they seek to increase the pervasiveness of information and skills relevant to good childhood nutrition.

However, in 2003 the government began to build a wide-ranging basic public health service system across rural areas. This system required the establishment of rural cooperative health care institutions, an increase in resources directed to rural areas, an increase in the provision of township and village health care facilities, and the cultivation of high quality medical personnel.

In some rural hospitals, facilities are still very rudimentary. “Some do not even have enough beds and all the scales are broken,” said Liu Bei, CDRF’s program coordinator. In big cities like Beijing, by contrast, community hospitals are usually equipped with specialized infant examination rooms full of toys.

The quality of personnel in rural hospitals is also less than ideal. CDRF has organized local hospital personnel in the pilot counties to train children’s mothers. However, Liu Bei discovered that many of the “trainers” also need to be trained.

Yu Gui says that no one ever told her she should take her son for a checkup. Every month when she goes to the rural health clinic to get immunizations the village doctor measures the baby’s height and weight, but he has never tested the baby’s hemoglobin or micronutrient status. This is not only the case for Yu Gui: in REAP’s survey they found this to be the normal state of affairs. Many mothers do not receive any nutritional information either during hospital medical checkups or during home visits from health department personnel.

The health department’s work is still focused primarily on family planning. In Tai Shan Miao Township the health department cadre sent Yu Gui the “Information Packet for Married Women of Child-bearing Age.” Inside were the Ningshan County government official family planning materials but there was no helpful nutritional guidance. Also, at the village level there is now less and less emphasis on family planning or health. The family planning cadres are often working part time and only receive a subsidy of about 200-300 RMB per year. They simply cannot afford to do more.

At the same time, past family planning work has brought about widespread resentment that also poses an obstacle to the provision of good health services. Starting around 2010, health departments across the region began providing free folic acid supplements to pregnant mothers in order to lower the rate of birth defects. However, according to reports, the impact was far from ideal. Many villagers did not accept the supplements, fearing that they were really a form of contraceptives. According to the author’s understanding, in many places the local health services personnel did not make much of an effort and the folic acid supplements were never successfully distributed.

In fellow developing country Cuba, the situation is much better. Yang Yiming, a high-level advisor at the Child Development Center at Harvard University, has written an introductory article about Cuba’s comprehensive maternal and child health care system. In every community, pregnant women are provided with special rations of milk and bread. There are also child-rearing educational courses available to new mothers and their family members.

“The Chinese rural public health service system got a late start and has been developing along a set order of priorities,” says Lu Mai. “However, there remains a pervasive problem of insufficient awareness and attention.” Lu Mai has referenced the views of numerous nutritional experts to point out that children’s nutrition is in many ways a “public good.” He believes that improving children’s nutrition is a very valuable human capital investment and therefore the government should take on the responsibility for improving children’s nutritional status. Whether or not to implement child nutritional interventions is often not a question of financial resources, but rather depends primarily upon whether or not the government is willing to make this issue a high priority.

How to Achieve a Successful Intervention Program

In 2001 Chen Chunming, the first president of the Chinese Academy of Preventative Medicine (now renamed the Chinese Center for Disease Control), launched a nutrition package intervention in five poor counties in Gansu Province. Ten years of tracking later, the program’s effectiveness is now obvious. A stately woman of more than 90 years of age, Chen Chunming is always emphasizing that children’s nutritional interventions should start before two years of age.

She has pointed out many times that childhood undernutrition is primarily the result of babies over 6 month’s old being fed poor quality complementary foods. In China, complementary foods traditionally include rice porridge, flour paste, noodle soup and other similar grain-based foods. These foods are not nutrient dense. They all include minimal amounts of protein, fat, vitamins and minerals. These nutritional inadequacies necessarily affect the child’s skeletal and brain development, among other important negative consequences.

The research data clearly shows that 9-24 month-old children have much greater nutritional needs than adults. To take the case of iron intake, for instance, 1-3 year-old children require about 0.54 ug of iron per kilogram of body mass. This is fully 7 times the nutritional requirement for a 20-25 year old young man! Moreover, brain development takes place primarily at a young age: the growth of the brain’s lifetime supply of neurons is 80% completed by the time a child reaches 2 years of age. Within the first three years of life, a child’s weight increases 5 times faster than his or her height. If a child is not getting enough nutrition, the damage within the first two years of life is irreversible.

Zhu Zonghan, president of the pediatrics branch of the Chinese Medical Association, is also a longtime advocate for the importance of infant nutritional interventions. He has told Caixin reporters that many studies have shown that it is very difficult to improve rural households’ infant feeding practices. Therefore, many researchers have begun searching for ways to quickly and effectively distribute nutritional supplement packages.

The results of numerous studies overseas and in China testify to the effectiveness of nutritional supplement interventions. In 2006, the CDRF turned its attention to the problem of childhood malnutrition. In cooperation with Chen Chunming, they began to investigate the possibility of a large-scale expansion of the nutritional supplement intervention model, with their eyes set on promoting far-reaching distribution through government policy.

In 2009 and 2010, the CDRF unfolded two separate arms of its “Early Childhood Development in Poor Areas Project” in Qinghai and Yunnan Provinces. This is an integrated project involving three primary interventions. First, pregnant women were provided with free prenatal vitamin tablets from the time of conception until they had given birth. Second, babies between 6 and 24 months of age were provided with free nutrition packages containing soybean meal with a full daily dosage of essential vitamins and minerals. Finally, in township hospitals and village clinics they established a monthly or bimonthly “Mommy School” to provide pregnant women and parents of babies under six months of age with nutritional and health care training.

In order to actualize this program, the CDRF cooperated with local government and relied on the current health system for implementation. The county health department made use of its collective meeting time to make a plan for the distribution of nutrition packages to township hospitals. Then each township was tasked with coming up with its own methods for getting those nutrition packages into the hands of villagers. Some of the township hospitals made use of the “Mommy School” class time to give the nutrition packages to parents. Others distributed the nutrition packages through village clinics. The foundation gave the township hospitals and the village clinics the funds they would need for implementation. Village clinics, for instance, received a 60-100 RMB monthly subsidy. Babies’ mothers were also offered a “conditional cash transfer” to encourage them to attend “Mommy School.” Each time they attended, the mothers were given a 10-20 RMB subsidy. Local health personnel also gave mothers nutritional information that was prepared by the Chinese Center for Disease Control including a comparison table showing standard height and weight for babies of varying ages.

As of the end of 2011, the CDRF’s project had been implemented in 19 townships spread across two counties, one in Qinghai Province and one in Yunnan Province. In total, 4,972 babies aged 6-24 months and 3,877 pregnant women received the nutrition package intervention. 61 “Mommy Schools” were successfully established. The compliance rate in Qinghai’s Ledu County was 70-80% and in Yunnan’s Xundian County was 80%. The effectiveness of the intervention was obvious. The children’s anemia rate fell by 40%. According to the CDRF’s calculations, the total cost for purchasing and transporting one nutrition package is about 0.7 RMB. Including the cost of implementation, this program could be undertaken at a cost of 1 RMB per child per day.

“One result that the baby’s mother can observe directly is that her child gets sick less often,” said Lu Mai. “This year I went to Xundian [in Yunnan Province]. I had been there three years before, and they were all very happy to see me again. They came out holding their babies and told everyone how we had given them nutrition packages.” The CDRF has since submitted reports to the Ministry of Health and the State Council based on the situation in these pilot counties.

According to the author’s understanding, in 2008 the Chinese Center for Disease Control, the World Health Organization (WHO) and the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) supported a project providing relief in the aftermath of the devastating earthquake in Sichuan Province. In 2011, the former Ministry of Health, the National Women’s Federation and the China Children and Teenagers’ Fund began implementing the “Eliminating Infant Anemia Operation” in poor rural areas of northwest China. In both of these cases, the organizations involved made use of nutrition package distribution program model. The participants have all suggested that the programs were very effective.

On the foundation of this research and these projects, in December of 2012 the former Ministry of Health and the National Women’s Federation jointly launched the “Poor Region Child Nutrition Improvement Pilot Program” in 100 counties across China. The central government specially allocated 1 billion RMB of funding for the project. They hope to reach 274,000 infants between 6 months and two years of age and provide each child with nutrition packages at a cost of 1 RMB per packet per child per day. Based on this reporter’s understanding, the second phase of the project is about to begin. In this next phase, the project will be expanded to 300 counties. After the over-arching plan, referred to as the “National Outline for the Development of Children in Poor Areas,” is passed, all 0-36 month infants in the 680 nationally designated impoverished counties will receive the nutrition package intervention.

Sustainable Health Solutions

Unfortunately, the 100 pilot counties in which the program has already been implemented have some problems.

“This program is supported by the local common people,” says Zhu Zonghan. “But the money provided by the national Ministry of Finance does not include the costs of implementation and training. Instead, the Ministry expects the local government to cover those costs. What poor counties have that kind of money?” Now Zhu Zonghan is also a member of the committee of experts for the Poor Region Child Nutrition Improvement Pilot Program. In that position, he has traveled to many of the pilot counties this year. He reports that the local Health Bureaus and local branches of the Women’s Federation are now doing volunteer work, but he worries that their current enthusiasm may not last forever.

The plan formulated by the Ministry of Health calls for the integrated distribution of nutritional supplement packages and nutritional knowledge training. The training sessions will be designed in accordance with the nutritional handbook drawn up by the committee of experts. This handbook will be given to parents along with the nutrition packages. The training sessions will be divided by level: first the experts will train the county-level personnel, then the county-level personnel will train the local personnel. The National Health and Family Planning Commission has set a goal of 80% compliance.

However, as Scott Rozelle has seen in Shaanxi Province, some townships are keeping the nutrition packages in the township hospitals with the intention of giving them to parents when they bring their babies in for health checkups. However, many parents never bring their babies in. Furthermore, some local health personnel are not providing any training to parents at all. In reality, according to REAP’s calculations, the aforementioned costs could all be covered by only 1 RMB. From the perspective of the CDRF’s Lu Mai and Liu Bei, it is essential to hold to international standards for the program’s implementation and training costs. And that training is necessary. Indeed, the nutrition packages are secondary—the most important task is to help parents attain a rudimentary understanding of good nutrition. Liu Bei also believes that if parents cannot be trained, compliance in the use of the nutrition packages will be very difficult to guarantee. If the parents do not cooperate, the nutrition packages will certainly never make it into their children’s mouths.

The REAP team hopes to find a low-cost solution to some of these challenges. They are currently conducting a study across 11 counties in Shaanxi Province. They are investigating the trade-offs between a three-month and a six-month supply of nutrition packages. They have also designed a new concise and colorful training handbook that training personnel can use to simply and clearly explain basic infant nutrition within ten minutes. REAP researchers believe that this task can be taken on by local personnel. They are also investigating the effectiveness of sending a daily text message reminding parents to give their children the nutrition package. If this is effective, it will be a low-cost way to increase the rate of compliance with the intervention.

Lu Mai has emphasized the utmost importance of carrying out a project evaluation. The planning committee has already commissioned the Chinese Center for Disease Control as well as several universities to do an evaluation of the situation in the original 100 pilot counties. The CDRF has also pledged its commitment to a large-scale evaluation of its implementation methods once the program has been rolled out in 300 counties.

The more important question is how to promote poor rural children’s comprehensive development. Besides directly distributing nutrition packages, there are many other health and education plans incorporated under the State Council’s “National Outline for the Development of Children in Poor Areas” that have yet to be implemented. Some of these focus areas include: nutritional meal interventions for 4-6 year old children; developing a system of health checkups; decreasing the rate of birth defects; ensuring food safety; and establishing new programs to bring education to previously underdeveloped regions. For all of these issues, effective change cannot be brought about without an increase in investment in rural health and education public services as well as the establishment of more effective and rational governmental mechanisms. And of course, it will be necessary to move forward in organic cooperation with the wishes and the support of the people.

The CDRF and REAP are also making plans for further research in the area of early childhood care. The CDRF has plans to select two counties out of the State Family Planning Commission’s original 100 pilot counties. In those two counties, the local health personnel will be instructed to go into parents’ homes to conduct early childhood nutritional training sessions for both parents and for their children. The CDRF will then compare the results in these two counties with those in the pilot counties that only received the pure nutritional package intervention. There already exists a very large gap between urban and rural areas in terms of early childhood education.

“We’re hoping to give hope to rural children,” says Lu Mai. “We want these kids to have every possible opportunity for the future.”■